Taylor on the Nile

©Arlene R. Taylor, PhD www.arlenetaylor.org

I pinch myself. Yes! I pinch myself again. Yes again! It is not a dream. I am really awake and I am really here! I am sailing up the Nile—going south—on the MS Miriam.

I pinch myself. Yes! I pinch myself again. Yes again! It is not a dream. I am really awake and I am really here! I am sailing up the Nile—going south—on the MS Miriam.

Reclining against a bank of soft pillows in my ground-floor cabin, I watch an ever-changing panorama. Buildings of Luxor pass in and out of view, some new and some ancient. Women wash clothes along the river’s edge. Children play nearby, running through lush green vegetation or jogging along on the backs of little white donkeys. A gentle breeze ruffles curtains framing the picture window that occupies the entire wall. A felucca slips by floating north, with the current, its sail billowing gently in the wind.

White herons move stealthily among the bulrushes, multi-generational offspring of bulrushes that may have hidden the little Moses. Were similar storks stalking frogs the morning the Egyptian Princess reportedly found the babe floating in a basket? Beyond the belts of green that frame the Nile stretches the desert. That vast shifting region of sand and stone where not one blade of grass breaks the color scheme of beiges, browns, and grays. The desert begins as abruptly as the vegetation ends, the demarcation as sharp as a line drawn in the sand by a sharp stick. Lush green on one side; mysterious desert on the other.

White herons move stealthily among the bulrushes, multi-generational offspring of bulrushes that may have hidden the little Moses. Were similar storks stalking frogs the morning the Egyptian Princess reportedly found the babe floating in a basket? Beyond the belts of green that frame the Nile stretches the desert. That vast shifting region of sand and stone where not one blade of grass breaks the color scheme of beiges, browns, and grays. The desert begins as abruptly as the vegetation ends, the demarcation as sharp as a line drawn in the sand by a sharp stick. Lush green on one side; mysterious desert on the other.

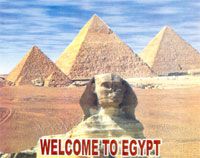

My earlier trip to Egypt in the last century had centered on Cairo, Memphis, and Giza. On that occasion I had awakened the first morning to sunlight streaming in through a gap in the window coverings. Getting out of bed, stretching, wiping jet lag from my eyes, and pulling back the drapes, I had gasped. A great pyramid, holding nearly 5000 years of history, stared me in the face. And that was when, still in my travel night shirt, I’d fallen in love with Egypt.

Now, in addition to reprising visits to Cairo, Giza, and Memphis, my travels would expand southward to Luxor, Aswan, and Abu-Simbel. When I open the drapes this time, it is not to the sight of a pyramid but to that of a garden terrace sprawling across the back of the Cairo Marriott. Built around one of ex-King Farouk’s 19th century palaces, my room offers a view of gold filigree, Moorish archways, and tiled walkways. The entire compound is located on an island in the great delta that forms the gaping mouth of the Nile River. The longest river in the world, it meanders for a mere 4184 miles from one of its sources, Lake Victoria. Located within an elevated plateau in the western part of Africa's Great Rift Valley, Lake Victoria is the continent’s largest lake and the largest tropical lake in the world. Its outflow in Uganda forms the Victoria Nile.

Now, in addition to reprising visits to Cairo, Giza, and Memphis, my travels would expand southward to Luxor, Aswan, and Abu-Simbel. When I open the drapes this time, it is not to the sight of a pyramid but to that of a garden terrace sprawling across the back of the Cairo Marriott. Built around one of ex-King Farouk’s 19th century palaces, my room offers a view of gold filigree, Moorish archways, and tiled walkways. The entire compound is located on an island in the great delta that forms the gaping mouth of the Nile River. The longest river in the world, it meanders for a mere 4184 miles from one of its sources, Lake Victoria. Located within an elevated plateau in the western part of Africa's Great Rift Valley, Lake Victoria is the continent’s largest lake and the largest tropical lake in the world. Its outflow in Uganda forms the Victoria Nile.

On the outskirts of Cairo stand the best known symbols of Pharaohic power and some of the most amazing treasures from the ancient world—the Egyptian pyramids and Sphinx. Built on the west bank of the Nile, the site of the setting sun, they were associated with the realm of the dead in Egyptian mythology. Most pyramids were built for the Pharaohs and their consorts during the Old and Middle Kingdom periods. Several of the Giza pyramids are counted among the largest structures ever built. The great Pyramid of Khufu, the largest and the only one of the seven wonders of the ancient world still in existence, still towers into the sky. Built of two-and-a-third-million blocks, each weighing several tons, it is no wonder that nine million visitors annually gaze with awe on the massive structure.

The light and sound show, playing on and around the pyramids scattered over the Giza plateau, transport us back eons: he grandeur of the Pharaohs, the mystery of their culture, the murmuring of secrets on the desert air, the wonder of papyrus, the chemistry of embalming... What a different world and yet somehow familiar: the quest for power, the intrigue of jealousy, the desire for immortality, the ego of legacy. Part and parcel of the human condition they’re all still here thousands of years later. Only the trappings differ.

The light and sound show, playing on and around the pyramids scattered over the Giza plateau, transport us back eons: he grandeur of the Pharaohs, the mystery of their culture, the murmuring of secrets on the desert air, the wonder of papyrus, the chemistry of embalming... What a different world and yet somehow familiar: the quest for power, the intrigue of jealousy, the desire for immortality, the ego of legacy. Part and parcel of the human condition they’re all still here thousands of years later. Only the trappings differ.

Three days later I am heading to Luxor (formerly Thebes). Once we clear security at the Cairo airport, which makes American-airline security seem rather perfunctory, the flight is uneventful. From the window of the plane the delta below resembles a giant lotus flower in bloom, the symbol of Egypt on many an ancient temple column and source of a most fragrant essence.

The Program Director and guide assigned to our group is one of the best I have ever encountered. In his mid-thirties with a master’s degree in ancient Egyptian history, he is a veritable fount of information. His penchant for presenting details through stories and humor, in a voice as fluent in English as Arabic, albeit with a slight British accent, is easy to hear. Depending on the current state of the economy, tourism can be the number one, two, or three source of income for the country. Their citizens take it seriously, having experienced how quickly the numbers can drop. After the catastrophic tourist killings in the late 90s near Queen Hatshepsut’s Temple, for example, tourism fell to 3% of its typical rate and the government took immediate steps to enhance security for its visitors. Armed guards everywhere lend an oxymoronic presence—safety on one hand and window dressing on the other. Either way, their dazzling uniforms and military bearing lend pageantry to the panorama.

Hence an armed escort as we leave the Luxor airport and head for the MS Miriam, our home away from home for the next even days. That escort would be reprised many times during the week. Sometimes as a front-back vehicle escort to the Valley of the Kings, sometimes as an armed walking presence to the Sphinx, and sometimes as a plain-clothes detective riding in the bus itself. The soldiers, their crisp white uniforms gleaming ‘neath the desert sun, appear serious about their responsibilities (this is no time to crack jokes), while at the same time exhibiting the very soul of hospitality and assistance.

Hence an armed escort as we leave the Luxor airport and head for the MS Miriam, our home away from home for the next even days. That escort would be reprised many times during the week. Sometimes as a front-back vehicle escort to the Valley of the Kings, sometimes as an armed walking presence to the Sphinx, and sometimes as a plain-clothes detective riding in the bus itself. The soldiers, their crisp white uniforms gleaming ‘neath the desert sun, appear serious about their responsibilities (this is no time to crack jokes), while at the same time exhibiting the very soul of hospitality and assistance.

High minarets in every town and community mark local mosques. Five times each day from high towers the sound of chanted prayers float out on the breeze. Although our guide is Muslim he has a travel exception and can make up his prayers at tour’s end. At each destination the Egyptian people seem genuinely glad to welcome us to their area, pleased that we are interested in their country and culture. When they discover this is my second visit, they go out of their way to ensure I have a rewarding experience. No doubt my white-blond hair and obvious walking-stick help.

Aboard the MS Miriam,a typical Nile-River boat, a central ground floor reception area serves as the hub. Stairs lead down to the dining room, which means that passengers eat their meals below water level, waves lapping gently just below high windows. Stairs also lead up through two floors of river-boat cabins to the roof with its swimming pool and hot tub. Sitting beneath canvas canopies on Cleopatra-style chaise lounges, it is easy to picture royal barges traveling between Memphis and Thebes (now Luxor) and farther up river. I imagine Egyptian royalty sipping nectar from silver goblets nibbling fresh dates, pomegranates, nuts, baby bananas, olives, and you name it, while Nubian slaves wave giant feather fans to keep the air pleasantly stirred.

Below the high dam, settlements along the river banks are small. The farther way from Cairo, the more they are steeped in tradition. Children splash naked in the shallows unafraid, knowing that the famous Nile crocodiles live south of the high dam around Lake Nasser. Acres of sugar cane and date palms sway in the breeze. Bullocks, goats, donkeys, and the occasional camel graze on small patches of green that slope down to the river’s edge. How different from the teeming streets of Cairo and Alexandria where more than half of the 77 million Egyptians reside.

Below the high dam, settlements along the river banks are small. The farther way from Cairo, the more they are steeped in tradition. Children splash naked in the shallows unafraid, knowing that the famous Nile crocodiles live south of the high dam around Lake Nasser. Acres of sugar cane and date palms sway in the breeze. Bullocks, goats, donkeys, and the occasional camel graze on small patches of green that slope down to the river’s edge. How different from the teeming streets of Cairo and Alexandria where more than half of the 77 million Egyptians reside.

Side trips by camel, cart, cab, or carriage take us to view hand-woven carpets and papyrus pictures. At the perfumeries personnel dab drops of floral extracts on our skin so we can discover how the fragrance combines with our own unique chemistry—and love or hate the results. My favorite is essence of Lotus, the flower of Egypt. Its scent is both intriguing and seductive. We learn that most of the floral extracts are shipped from Egypt to Europe, diluted with water and alcohol, and resold at enormous prices under such exotic names as Emeraude, White Diamonds, White Shoulders, Evening in Paris, and Channel No. 5 for women; and under Eau Sauvage, Drakkar Noir, Obsession, and Eternity for men; plus new metrosensual offerings.

The temple of Karnack, situated at one end of the royal road that connects it with the Luxor temple at the opposite end, sets the stage for ruins to come. Scores of carved sphinxes line both sides of the royal road. One can only imagine how they looked in their heyday. Our guide, Mohamed (half the men in Egypt seem to be named Mohamed) makes it easy for us to grasp the procession of Egyptian dynasties—well, sort of. We begin to recognize the period of history represented by the style of carvings on pillars, statues, and facades.

On the opposite bank from Karnack, Queen Hatshepsut’s Temple sprawls in all its royal magnificence. We marvel at the sheer scope and magnitude of the architecture and also at the anger of Thutmose III, her stepson and successor. What must have happened between them to prompt the sixth Pharaoh of the Eighteenth Dynasty to systematically deface all her statues and monuments? How he must have hated her! The style of the temple and drawings of pools and plants that formed part of the original landscape were innovative for their time, to say the least. They were a definite departure from some of the other ruins we had already viewed.

On the opposite bank from Karnack, Queen Hatshepsut’s Temple sprawls in all its royal magnificence. We marvel at the sheer scope and magnitude of the architecture and also at the anger of Thutmose III, her stepson and successor. What must have happened between them to prompt the sixth Pharaoh of the Eighteenth Dynasty to systematically deface all her statues and monuments? How he must have hated her! The style of the temple and drawings of pools and plants that formed part of the original landscape were innovative for their time, to say the least. They were a definite departure from some of the other ruins we had already viewed.

Five o’clock in the morning. The phone rings, my cue to fall out of bed, dress in long-sleeved cotton, and go down to breakfast. Although it is fall in Egypt, heat from the sun, in the Valley of the Kings can be blistering by early afternoon. Our guide wants us on the bus by 7 o’clock so we can be finished sightseeing by noon.

Escorted front and back by military jeeps, our bus winds through rocky desert for nearly an hour. As our eyes become adjusted to the terrain, it becomes easier and easier to spot openings that dot the hillsides; burial chambers of governors and other nobility.

Escorted front and back by military jeeps, our bus winds through rocky desert for nearly an hour. As our eyes become adjusted to the terrain, it becomes easier and easier to spot openings that dot the hillsides; burial chambers of governors and other nobility.

Tombs in the Valley of the Kings are spacious, as unlike the cramped tunnels and underground burial chambers of the pyramids as night is from day. The tombs are in the desert, however. Not a blade of green is visible as we leave the bus and begin a half-mile sloping walk up to a cluster of tombs.

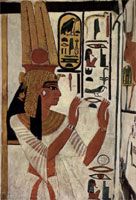

Carved into solid sandstone and protected from the elements for thousands of years, many paintings inside the tombs are still vibrant with color. We recognize some of the hieroglyphs through Mohamed’s stories. The sarcophagi that remain are massive and magnificent. What a feat to have transported them down the Nile by barge, up the desert hills for kilometers, and finally down the decorated hallways to their final resting place.

Small rooms carved off the main tunnel were once stuffed with everything and more that the resident of the sarcophagus might possibly need on his/her journey through the underworld to the next life. Little if any treasure remains in the actual tombs, but after marveling at them in the Cairo museum, it’s easy to imagine how the storerooms must have looked.

Smart man, our guide. We appreciate Mohamed’s foresight as we leave the tombs and see busloads of tourists just arriving in the Valley of the Kings. It is hot and we eagerly drain the bottles of water the bus driver provides. Now to reboard the MS Miriam for a late lunch and siesta. Tonight is another adventure of sound and light with the option of a folklorico. Belly dancing—it takes years (so they say) to gain the precise muscle control required. Not in my lifetime!

In an ancient quarry near Aswan, we view an unfinished obelisk. Planned to be the largest ever quarried in Egypt, it lies there, all 137 feet of it at an estimated 1100 -1200 tons. Cracked down the middle, it was never finished. It does provide insight into how existing obelisks were created, however. But how would the workers have lifted it from its bed, gotten it down to the Nile, and then transported it to its designated location? It boggles the mind!

In an ancient quarry near Aswan, we view an unfinished obelisk. Planned to be the largest ever quarried in Egypt, it lies there, all 137 feet of it at an estimated 1100 -1200 tons. Cracked down the middle, it was never finished. It does provide insight into how existing obelisks were created, however. But how would the workers have lifted it from its bed, gotten it down to the Nile, and then transported it to its designated location? It boggles the mind!

Back on board our Program Director gathers us in the main-floor lounge for a lecture about Egypt. For example, back in the mid nineties the literacy rate was something like 15% (could we have heard that correctly?). With a massive educational push and required school attendance estimates are that two-thirds of the people are now literate. Private schools are welcome as they reduce the strain on government schools. Again, however, the father away from Alexandria and Cairo, the more likely one is to discover pockets of illiteracy and a clinging to old customs and traditions that are no longer practiced in urban centers. He invites questions and is willing to answer any and all of them.

The captain navigates a set of locks on route to the Aswan High Dam. It was that and more—high and massive! Built by Nasser with aid from the Soviet Union (after Britain and the United States backed out from initial offers of financing), it changed the face of agriculture along the Nile. The dam—3,830 meters in length, 980 meters wide at the base, 40 meters wide at the crest, and 111 meters tall—forms a reservoir known as Lake Nasser. Now the country is no longer at the mercy of the annual spring floods. Crops are grown year around watered by irrigation canals, and electricity reaches even the smallest Egyptian communities.

At the Aswan airport, we board a plane that flies us into the region of Nubia. While it is virtually impossible to select a “best of show” the two massive rock temples at Abu-Simbel have to be near the top. Built by the third Pharaoh of the Nineteenth Dynasty, the structures are Herculean in scale and overwhelmingly impressive. Touted as Egypt’s most powerful ruler, Ramesses II has been associated traditionally with the Exodus and the emancipation of the Israelite peoples from slavery, the story of which forms the basis for the Jewish holiday of Passover.

At the Aswan airport, we board a plane that flies us into the region of Nubia. While it is virtually impossible to select a “best of show” the two massive rock temples at Abu-Simbel have to be near the top. Built by the third Pharaoh of the Nineteenth Dynasty, the structures are Herculean in scale and overwhelmingly impressive. Touted as Egypt’s most powerful ruler, Ramesses II has been associated traditionally with the Exodus and the emancipation of the Israelite peoples from slavery, the story of which forms the basis for the Jewish holiday of Passover.

Nefertari is known from the many paintings that adorn temple and tomb walls. Her burial chamber in the Valley of the Queens, built by Ramesses II, is reportedly the most beautiful of them all. Even her name is said to mean “the Most Beautiful of Them.” Our guide tells us that so far as it is known, no other Egyptian queen was held in such honor that a temple was dedicated to her jointly with a goddess.

Nefertari is known from the many paintings that adorn temple and tomb walls. Her burial chamber in the Valley of the Queens, built by Ramesses II, is reportedly the most beautiful of them all. Even her name is said to mean “the Most Beautiful of Them.” Our guide tells us that so far as it is known, no other Egyptian queen was held in such honor that a temple was dedicated to her jointly with a goddess.

The engineering that first carved the elaborate temples and all their columns and figures from solid rock in the 13th century BC beggars the imagination. The technology that lifted the two structures out of harms way in the 20th century AD is equally astounding. But for the far-sightedness of archeologists and the generosity of art lovers such as Jacqueline Kennedy Onassis, the great temples of Pharaoh Ramesses II and his beloved royal wife Nefertari might have disappeared forever beneath the waters of Lake Nasser behind the high dam.

The salvage operation itself began in 1964 and continued until 1968. Dismantled and raised over 60 meters up the sandstone cliff from the spot where they had been built more than 3,000 years earlier, the two temples were reassembled in the exact same relationship to each other and the sun and covered with an artificial mountain. It is difficult to stop staring.

After lunch we climb aboard a felucca. Its white sails catch the breeze and float us past the Aga Khan’s mausoleum and white villa on the west bank of Aswan. We sail around lush botanical gardens on Kitchener’s Island, so named because the British Consul (Lord Kitchener) was deeded the island by the Egyptian government in recognition of successful 19th century campaigns in the Sudan, far bey ond the high dam.

We dock at Elephantine Island. The oldest ruins still standing on this largest island at Aswan is a step pyramid dating back to the third dynasty. Disembarking, we ride the elevator in a luxury high-rise hotel for aft ernoon tea on the top floor. The 360-degree panorama matches the exquisite repast.

We dock at Elephantine Island. The oldest ruins still standing on this largest island at Aswan is a step pyramid dating back to the third dynasty. Disembarking, we ride the elevator in a luxury high-rise hotel for aft ernoon tea on the top floor. The 360-degree panorama matches the exquisite repast.

At ground level again, a quick trip by water taxi returns us to the MS Miriam. All too soon the captain fires its engines, makes a U-turn and we are floating down the river going north. Once more through the locks, past a myriad crumbling ruins to the dock at Luxor, and on to the airport for a return flight to Cairo. Only a few more days in Egypt.

Early morning and I’ve just finished my last breakfast at the palace. The van makes its way through the Cairo traffic toward the airport. At least five lanes of seething traffic crowd into four official lanes. On exit streets anything goes from donkey carts to tankers. The mules must have nerves of steel. Their funny little tails whirl a mile-a-minute as the animals plod along unconcerned midst camels and cars, negotiating their antique-modern world. All too soon I am once again passing through multiple security checkpoints on my way home.

Aboard the plane, I press my eye to the window to catch a last glimpse of Egypt’s meandering delta, fanning out below like an opening Lotus flower. I think I recognize the island from gold trim on the palace reflecting sunlight. One by one the pyramids fade into mist and haze. Finally all that’s really distinguishable is the ribbon of water flanked by twin borders of green. And beyond on either side, the desert as far my eye can see. The Valley of the Nile, one great museum. What secrets it still holds with perhaps 70% of its estimated treasures still undiscovered.

The plane bursts upward through a light cloud layer and the continent of Africa disappears from view. I still look out the window, hoping for a last glimpse of Egypt. My brain, stimulated by sight, sound, scents, stories, and scenery, has sprouted millions of new dendrites, What is it about this region that calls to me? Mayhap some ancestor traversed this land and bequeathed my cells with memory. All I know for sure, and “I know that I know that I know,” (smile) is that I already want to return.

Half-way around the globe and back home in Northern California, I stand in the hallway surrounded by a small collection of Papyrus paintings. One shows my name in hieroglyphics written inside a cartouche. Looking into the glass my mind’s eye sees again ancient pyramids of Giza, pictures the Valley of the Kings with its hidden tombs, imagines the great sphinx gazing steadily into eternity, visualizes the temple of Queen Hatshepsut with a camel caravan poised against the setting sun, and marvels at Abu-Simbel. Always Abu-Simbel. I hear myself sigh. I have fallen in love all over again—with Egypt. Gentle on my mind.