Going for Gold -- The New Neuroscience of “Choking”

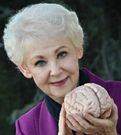

©Arlene R. Taylor PhD www.arlenetaylor.org

Watch your thoughts, they become your beliefs.

Watch your beliefs, they become your words.

Watch your words, they become your actions.

Watch your actions, they become your habits.

Watch your habits, they become your character.

—Vince Lombardi

His first words were, “What do you know about choking?” The question came from a physically fit young man who sat slumped on my office stool.

His first words were, “What do you know about choking?” The question came from a physically fit young man who sat slumped on my office stool.

Smiling, I replied, “Well, there’s choking that involves something getting stuck in your throat, and choking due to constricted bronchial tubes, and choking because of a scary game kids sometimes play, and performance choking linked with failure under pressure...”

“Performance choking linked with failure under pressure,” Bryan interrupted with a wave of his hand. “I’ve joined the ranks of Wimbledon’s Jana Novatna and golf’s Van de Velde. Not that I wanted to join, you understand.

Experimental findings have associated choking under pressure with four pressure variables: audience presence, competition, performance-contingent rewards and punishments, and ego relevance of the task. I explained these variables to Bryan and suggested he describe his most recent episode.

“The game was on the line. I missed both free throws. It is crazy! I’ve sunk 25 baskets in a row—in practice.”

“What were you thinking just before you threw the ball?” I asked.

Bryan shook his head. “I wanted those points desperately and knew the entire team was depending on me. I guess I lost my confidence, played scared, and started analyzing what my muscles should do instead of just trusting my skills.” A puzzled look spread over his face. ”It was like being back at the beginning when I first learned how to play.”

His explanation was on the money. Bryan had become incapacitated by his own thoughts, exerting too much conscious effort instead of trusting his highly honed skills. Referred to by some researchers as paradoxical performance effects, choking under pressure can be defined as inferior performance despite striving and incentives for superior performance. It certainly represents inferior performance in comparison with what the person can do.

A couple of theories may help you better understand what is happening:

- Explicit monitoring theory - Pressure raises self-consciousness and anxiety about performing correctly, which increases the conscious attention paid to skill processes and their step-by-step control. When humans fixate on themselves, trying to avoid mistakes or getting caught up in expectations, implicit learning fails. They lose the natural fluidity of performance and the grace of honed talent.

- Distraction theory - Pressure creates a situation of divided attention which interferes with single-mindedness. People start to lose concentration, allowing some of their attention to be diverted towards irrelevant stimuli such as worries, social expectations, and anxiety. Under situations of stress, embroiled in negative thinking, explicit learning takes over and disrupts performances.

The human brain sometimes fails under pressure. Millions have witnessed this phenomenon in the unexpected catastrophes of Olympic trials and in almost any high-stakes sports event—although the reasons may be worlds apart. In his article “The Art of Failure” (2000), Malcolm Gladwell describes the difference between panic and choking:

“Panic involves too little thinking and reverting to instinct, while choking represents too much thinking and a loss of practiced instinct. Although most people get nervous at some time or other, not everyone either panics or chokes.”

Matthew Syed, in his book Bounce: The Myth of Talent and the Power of Practice (2010), explains choking this way:

“Experts and novices use two completely different brain systems. Long practice enables experienced performers to encode a skill in implicit memory, and they perform almost without thinking about it. This is called expert-induced amnesia. Novices, on the other hand, wield the explicit system, consciously monitoring what they are doing as they build the neural framework supporting the task. But now suppose an expert were to suddenly find himself using the wrong system. It would not matter how good he was because he would now be at the mercy of the explicit system. The highly sophisticated skills encoded in the subconscious part of his brain would count for nothing. He would find himself striving for victory using neural pathways he last used as a novice. This is the neurophysiology of choking. It is triggered when we get so anxious that we seize conscious control over a task that should be executed automatically.”

“Choking does not have to happen,” I told Bryan. “It is not an inevitable flaw of performance.”

Recently Daniel Gucciardi and James Dimmock, psychologists at the University of Western Australia, studied 20 experienced golfers with handicaps ranging from zero to twelve, analyzing their success under three separate conditions. The best results were obtained when the golfers stopped thinking about the details of their swing or how to position their hips. When they contemplated a generic and vague cue word or phrase (e.g., “Smooth,” “Balanced,” “Enjoy this”), their performance was no longer affected by anxiety. The positive adjectives did not cause the athletes to lose the flow of expert performance or overrule their automatic brain.

Bryan and I discussed steps he could implement to avoid performance choking. “Keep it basic and simple,” I suggested. “Try using the acronym STP:”

- Stay in the moment. Think about what you need to do now—not about what just happened or even about the finish. Breathe slowly and relax your muscles for a moment to help you refocus.

- Take control of your mindset. When you become aware of a negative thought just note it and move past it immediately to a positive thought. Tell your brain what you want it to do. Use positive, present-tense words, your first name, and the pronoun you. “Bryan, you are sinking baskets. You are relaxed and enjoying the game.”

- Perform with pleasure. Trust your body and the skills you have developed. Remember how much you enjoy what you are doing.

“We have a big tournament coming up first of the year,” Bryan said, as he stood to leave. “I have some STP work to do between now and then.”

A team of neuroscientists in London used MRI studies to gain insight into choking. They found that as people got excited about potential rewards, activity tended to increase in a subcortical brain region (ventral striatum) that is dense with dopamine neurons. However, as the participants began playing the video game (albeit inside a brain scanner), activity in the ventral striatum changed. The brain activity became inversely related to the magnitude of the reward, i.e., larger incentives led to less striatum activity. And decreased activity led to decreased performance.

Loss aversion is a well-documented phenomenon: People feel worse over a loss than they feel good about a gain. For example, the pleasure of winning $1000 is less intense than the pain of losing the same amount. Although there were no actual ‘losses’ in the London experiment (e.g., participants were never punished for failure), the researchers theorized that the act of playing the game led the participants to count chickens that were not yet hatched and to think about wins that had not been achieved. Because of that, the ventral striatum that focuses on rewards showed less activity as the brain worried about possible failures. In fact, the most loss-adverse participants showed the largest drop in performance when the rewards were increased.

This suggests that some individuals ‘choke’ under the pressure of the moment because they care too much. They want to success and want to win so desperately that they unravel. The activity’s pleasure has vanished. What remains is the fear of failure, of losing, which can trigger choking.

“I didn’t do it!” the voice shouted when I answered the phone. “No—I mean, I did do it!”

Recognizing Bryan’s distinctive accent, I laughed, moved the phone further away from my ear, and asked, “Which is it?”

“It’s BOTH!” he shouted. “I avoided choking and we won.”

“Excellent,” I said. “What made the difference?”

“I stopped thinking about failure. Every time a negative thought crossed my brain, I changed it to a positive thought. I told my brain what I wanted it to do. You know, the STP strategy.” There was a pause. “There’s an exhibition tournament scheduled for early in the New Year. I would love for you to be there. Would you like a ticket? Shall I send you one?”

My answer was yes and yes.