The Only Way Is Up

©Arlene R. Taylor, PhD www.arlenetaylor.org

Each day of our lives we make deposits in the memory banks of our children.

—Charles R. Swindoll

“He hasn’t talked to us, except for a mumbled word or two, for nearly three weeks,” the woman said, tearfully.

“He hasn’t talked to us, except for a mumbled word or two, for nearly three weeks,” the woman said, tearfully.

“And he flunked his math test last Friday,” said the man. “Not like him at all.”

The middle-aged couple sat across the table from me. I’d agreed to meet for brunch to talk about concerns related to their 14-year old son, Jon. Their body language expressed anxiety and concern, notwithstanding the excellent food that was disappearing off our plates.

“Did he used to talk with you?” I asked, between bites of quiche.

The father nodded. The mother said, “Always.”

Silence.

“What triggered the change? Alterations in behavior never arise out of a vacuum. As one person put it, every pathology has an ecology.”

The father looked out of the window, seemingly studying the massive redwoods that reached for the sky. The mother looked at the floor, twisting the corners of her napkin.

I waited.

“Things have been a bit tense at our home lately,” the mother said finally, glancing at her husband.

Then the father spoke up, a mix of frustration and fear in his voice. “I was fired after 25 years on the job.”

I nodded.

“We began arguing over everything and nothing,” his wife continued. “A few weeks ago it escalated into a screaming match. When Jon tried to intervene, we screamed at him, too. It was as if a blind dropped down behind his eyes. It’s still there. As I said, except for answering direct questions with a word or two, he has been non-communicative.” She sighed and brushed beginning tears away.

“We blew it big time,” said the husband. “The only way is up, but we have no idea how to start the climb.”

“That’s an interesting comment,” I said, “considering you’re likely describing the natural brain phenomenon of downshifting. Yes, the only way is up but the problem is that while your behaviors can trigger downshifting in another brain, you cannot force that brain to upshift.”

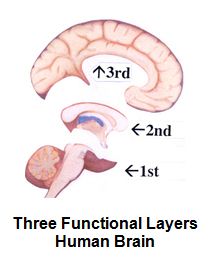

I explained how the brain can be described in terms of three functional layers, which metaphorically can be thought of as gears in an automatic transmission. In the face of fear or anxiety, the brain directs its energy and attention to lower brain layers, searching for functions to help it feel safer, a natural phenomenon known as downshifting. In the process the brain also tends to stop engaging in conscious cognitive functions such as meaningful communication. “Your brains were probably downshifted,” I told the parents, “triggering the fight or flight stress response housed in the first layer or gear. You chose fight. Your son appears to have selected flight, at least from communication.”

I explained how the brain can be described in terms of three functional layers, which metaphorically can be thought of as gears in an automatic transmission. In the face of fear or anxiety, the brain directs its energy and attention to lower brain layers, searching for functions to help it feel safer, a natural phenomenon known as downshifting. In the process the brain also tends to stop engaging in conscious cognitive functions such as meaningful communication. “Your brains were probably downshifted,” I told the parents, “triggering the fight or flight stress response housed in the first layer or gear. You chose fight. Your son appears to have selected flight, at least from communication.”

No child (boy or girl) likes to hear parental arguing and fighting (much less screaming), but studies have shown that these types of behaviors tend to be harder on boy brains. Parental arguing or divorce can place boy brains at higher risk for downshifting, a situation that could seriously derail communication and learning both at home and at school. In fact, it might take several years before the boy’s brain returns to learning readiness.

“But we’re not divorcing!” the husband exclaimed.

“Does your son know that?” I asked. “With all the arguing and screaming, I’d be willing to bet he fears that divorce is the next step.”

No longer just threatening, tears now rolled silently down the mother’s face.

“We’re desperate,” said the father. “Tell us how to get his brain to upshift.”

“Therein lies the rub,” I said. “Again, while your behaviors can trigger downshifting in another brain, you cannot force it to upshift.”

The silence was deafening as the information soaked in.

“There is good news,” I continued. “Since downshifting occurs in response to fear, anxiety, trauma, or perceived threat (e.g. something that invokes a sense of helplessness in the brain), you can set up the environment to help the downshifted brain feel safer. Under conditions of perceived safety, it may upshift on its own.”

Before I offered them suggestions, however, I had something else to recommend. “I think you need to talk with your son, together, calmly and honestly. You might begin by apologizing for allowing your own fears and anxieties to express themselves in negative behaviors, like arguing and screaming. Be honest about how difficult being fired is for the male brain and talk about what you are doing to become re-employed. Reaffirm how much you love him and each other and share your hope for a positive future.”

Looking at each other, they both nodded. So we jumped into examples of potentially helpful strategies. Strategies the might help their son’s brain feel safe enough to upshift.

Strategies for Dealing with Downshifting in Others

1. Use short, simple, positive statements.

Some believe that a portion of the 2nd brain layer or gear, (pain/pleasure center) rarely matures emotionally beyond the age of a four- or five-year-old child. Think about the ways in which you communicate with a child of that age. Short, simple instructions are usually most effective. This is not “talking down” to the person. Rather, it is recognizing that this style is likely to be more effective when communicating with a brain in a downshifted state.

Positive statements involve a one-step process. What you picture is what you get. Negative statements, the reverse of an idea, require a two-step process. The brain must change the first picture by imagining the opposite. The 3rd brain layer generally is capable of this, although speaking in negatives is not as effective as speaking in positives. This process is almost impossible for a child’s still-developing brain to pull off, however.

When the subconscious brain tries to process negatives (e.g., Don’t touch the stove), the brain initially creates a mental picture of touching the stove and may miss the word don’t. It is usually more effective to say, Keep your hand away from the stove. Negative comments, instructions, or thinking patterns can derail communication as the brain mentally pictures negative outcomes and may or may not create opposite pictures successfully.

2. Use present tense verbs.

All three brain layers can perceive and respond to present-tense language. (The subconscious layers likely respond to and follow the mental pictures the language created in the 3rd brain layer.) So regardless of which brain layer has the focus at that moment, communication can be perceived.

For example, say “Put your homework in your backpack now.” Avoid saying Don’t forget your homework or Remember to take your homework in the morning. Those are future tense statements, which may or may not be recalled in the morning.

3. Use congruent communication.

In order for the content of the communication to be transmitted clearly and effectively (to avoid mixed messages), the words, voice tonality, and nonverbals need to be congruent—in harmony, matching, coinciding with each other. If the conversation is serious, use serious facial expressions. If communication is happy or in fun, smile.

Congruent communication requires honesty. In a two-party communication, the message that comes across with the most impact will usually align with what you really think or feel. The truth will leak out in tone of voice and body language, regardless of the actual words you use.

4. Avoid asking the Why-question.

In many languages the word why can be perceived as stressful or threatening. It can imply an expectation that you should have done something different from what you actually did, and can create just enough anxiety to trigger downshifting. The response to “Why did you do that?” or “Why didn’t you do that?” is often a shrug or a mumbled Don’t know. And the brain likely does not know. It might be able to come up with some ideas that could have some bearing on the issue at hand, but in most cases not anything objective and definitive.

Use other words to elicit information or stimulate discussion. Try instead:

- What did you want to have happen in this situation?

- When you made this choice what did you think might occur?

- What could you do differently in the future to achieve a different outcome?

5. Sit down when conversing.

When both parties are at eye level. the fear and anxiety potential can be reduced. In addition, studies have shown that when both parties are seated the brains tend to perceive time differently, often estimating more time passed than actually went by. Speak in a calm, steady, moderately-pitched voice. Listen to the words the other person uses, watch his or her body language and mirror the other person’s words and communication style—auditory, visual, or kinesthetic.

If the person says, “That’s unclear to me” (which might indicate a visual sensory preference), a reply such as “Well, let me try again and see if you can hear what I’m saying” (auditory sensory preference) or “You need to get a handle on this so pay attention (kinesthetic sensory preference) will likely sound foreign and uncomfortable to the other brain. The brain tends to feel safer and more comfortable when it perceives both parties are speaking the same language, sensory as well as linguistic.

6. Solicit the other person’s input.

Listening can promote a feeling of being heard and even understood, whether or not you agree with the perspective. Even when you differ, it’s not always helpful or even necessary to point out areas of disagreement. If possible, try to identify commonality, even if there are areas of disagreement. Sometimes you can agree to disagree because it really doesn’t matter.

Ask yourself, “Will this make any difference twelve months from now?” If the answer is no, avoid wasting time and energy on it. Sometimes you can just agree to disagree. If the answer is yes, then negotiate to consensus, understanding that the solution will work only partially for both parties and there will need to be areas of compromise.

7. Provide options for making choices.

The brain feels safer when it can choose and make a decision. Whenever possible allow the other person to choose between two options—never more than two at a time because the brain only has two cerebral hemisphere). Select options whether either is fine with you, and simply offer both as a way to help the other brain choose and feel safer.

They can be simple options: “Will you take the chair or the stool?” “Do you prefer water or 7-Up?” “Do you want the door open or closed?”

Buy-in often can be enhanced by a sense of participation. If there is no option at the moment for an entire decision, provide the other person with an option to exercise some control over part of an activity if not over the entire activity.

“How far the brain downshifts and when and if it upshifts depends on the degree of threat that brain perceives,” I reminded them. “Just keep using the strategies and avoid behaviors that are known to be high risk for triggering downshifting.”

They left, hand in hand, smiling. Granted, the smiles were a bit tenuous but they were there. I felt hopeful for Jon. For them, too, for that matter.