Crocodiles and Waffles

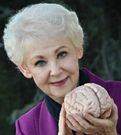

©Arlene R. Taylor PhD www.arlenetaylor.org

Candie threw on her robe and climbed stealthily down from the loft. Navigating the slumbering cousins sacked out on the floor, she tiptoed to the kitchen and carefully pulled the door closed behind her. There would be thirteen hungry mouths for breakfast—nine visiting relatives plus her own family of four. To say nothing of the two dogs and a parrot!

Candie threw on her robe and climbed stealthily down from the loft. Navigating the slumbering cousins sacked out on the floor, she tiptoed to the kitchen and carefully pulled the door closed behind her. There would be thirteen hungry mouths for breakfast—nine visiting relatives plus her own family of four. To say nothing of the two dogs and a parrot!

One large pot of bubbling porridge and four-dozen blueberry muffins later, Candie slowed down long enough to pour herself a cup of steaming hot chocolate. She nearly dropped it, however, and let out a startled squeak as Jake’s mother suddenly appeared in the doorway. Walking over to the stove, she lifted the lid from the pot, sniffed its contents, and commented, “You’re not making waffles.”

Candie groaned inwardly, set down her cup, and leaned her arms against the counter. She wanted to say, “Brilliant; you know the difference between porridge and waffles!” She didn’t. Instead she asked, “Anything wrong with porridge?”

“I didn’t say there was anything was wrong with porridge,” her mother-in-law retorted through pursed lips.

“You know I can’t make waffles for thirteen out here in the woods,” Candie replied in a voice of studied calm. “Pancakes maybe; not waffles.” And, she thought to herself, if I had made pancakes, she would have said that porridge was healthier. I can never win with her. Candie took a deep breath, pasted a smile on her face, and asked, “Would you like a cup of coco before the stampede begins?”

The older woman shook her head and headed for the wide porch. She looked out over the lake and murmured, just loud enough to be heard, “You’re always so defensive. I just asked a simple question!” Or had she?

Spoken language has at least two levels: the actual words used in the communication, and the underlying message-the meaning that often mirrors our actual intent. Deborah Tannen refers to these levels as the word message and the heart message. Influenced by past history, most people tend to react most strongly to the heart message. Candie certainly did!

Studies show that the words themselves convey about 10% of the communication message, with the other 90% being transmitted through the rate of speech, voice inflection, and body language. Think of these communication components as resembling a partially submerged crocodile, its snout poking out above the water.

On the surface, Jake’s mother had asked a simple question. But if she’d been satisfied with the porridge, she wouldn’t have mentioned waffles. Or she might have been upset about something else, and rather than address it directly had permitted her irritation to slip out in relation to the menu. It’s a big deal to Candie because her perception is that she can never get it right, can never please her mother-in-law. Plus she’s pretty sure that Jake will hear about his testy wife. That will put him in the middle again. If he sides with Candie, then his mother gets upset; if he agrees with his mother, then Candie feels betrayed. “It’s going to be a very long week,” she mused and, with a sigh, went to wake up the rest of the family.

We cannot get through life without pain. Unfortunately the very structure intended to help us deal with pain—our families—often triggers it. Especially emotional pain! Family members share a long history, and much of what they say to each other contains echoes from the past. This can be a mixed blessing. On one hand it allows for a type of verbal shorthand because of the common-knowledge-in-the-family factor. On the other, conversations in a family system rarely stand alone. Rather they are part of the overall and ongoing web of communication. Depending on the content and the setting, these interactions can often set off reactions that, interestingly enough, might not occur with non-family members.

Of course reactive patterns can be learned and repeated outside the family system, too. For example, during childhood if we had difficulty turning out the light at night because our brains really got going about 8 o’clock in the evening, we may have been repeatedly subjected to the old adage “early to bed and early to rise,” or scolded for staying up late, or shamed for being a sleepy head for slumbering until mid-morning. In adulthood if someone asks us what time we turned in the night before, our brains may connect that question to earlier pejoratives, and we may respond defensively with some retort such as, “What’s it to you?” Or “Mind your own business!” Or, “I know how much sleep I need!”

Reactions can be further magnified when conversing with family members who assume they have a duty to be critical (helpful is the word they would prefer to call it). After all, they care about us, don’t they? Or when we’re trying to communicate with individuals who boost their own sense of self-worth by deliberately finding fault with others, often couching their criticism in questions or comments that sound innocent enough. Regardless of the actual words, however, one’s intent usually oozes through in the underlying message, whether or not the individual is aware of that on a conscious level. The receiver typically reacts to the heart message, while the sender, if questioned, tends to stick by the word message and ignore the heart message. This mismatch can create a dysfunctional communication loop that often intensifies with time.

The only really effective way to get out of a dysfunctional communication loop is to address the heart message, to drain the swamp as it were, and bring the whole crocodile into view. One of the parties must break the mismatch cycle! Candie could respond with, “I feel like you’re displeased with my choice of porridge.” If there had been no intent to criticize, Jake’s mother would be handed the opportunity to become aware of how her words had been perceived, and she could come back with, “I know porridge is the best choice in this setting, but I’d like to put my order in for waffles next time we’re at your place. I love the way you make them.” On the other hand, if there had been some hidden agenda in her in-law’s comment, Candie’s response would serve as gentle notice that she was aware of the underlying message.

Bottom line? Over time, the cumulative affect of negative communications and reactions can undermine relationships. A good place to begin is to ask yourself, “What message do I intend to convey? Criticism or caring?” It may require some honest introspection to become aware of hidden agendas that can turn into lethal landmines. Make certain the word message and the heart message of your communication match-affirmingly.

And speaking of waffles...