Like most people I grew up learning about the five senses: sight, smell, hearing, taste, and touch. Some of this came from watching my parents teach my baby brother to point to his nose or tongue, ears or fingers. Thanks in part to information disseminated through Neurolinguistic Programming or NLP for short, much more is known today about the senses than ever before. There has also been a move to refer to the senses in terms of three main sensory systems:

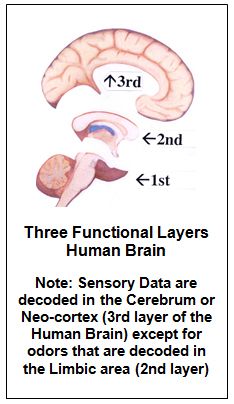

Areas in the brain specially designed to decode and interpret incoming sensory data are able to receive and interpret up to 10 million bits of sensory data per second¾far more than human beings are capable of processing at a level of conscious awareness. For the most part, these decoding centers are located in the two posterior divisions of the human cerebrum (refer to drawing to the right).

That exception involves the decoding of odors (e.g., the sense of smell). This decoding and interpretation of odors appears to occur in the limbic system, a subconscious layer of the brain. Because this portion of the brain is also involved with the storage and recall of memories, odors may trigger memories faster than any other type of sensory data.

No surprise, human beings perceive the world, process information, learn, and communicate through their senses. It will be big news if anyone figures out a way in which humans communicate without using any of the senses.

The seemingly magical dynamic between two people whose brain’s “click” is often referred to as rapport. It has everything to do with communication. The great thing about rapport is that you can build it even if it didn’t seem to “click” right away. Rapport is the ability to sustain good communication with someone even when you strongly disagree on an issue. You don’t have to be right; you don’t have to be wrong. It can be helpful to understand that each brain has its own opinion or perception and likely a personal sensory preference.

When you communicate with others in their preferred sensory system you build a greater understanding, strengthen your rapport with them, and increase your ability to influence. Miscommunications can occur when the individuals have different sensory preferences.

You may have heard the saying “talk the talk” or “speak their language.” There are no tricks to this. The strategy simply requires listening to the other person carefully enough to pick up on the type of words and phrases that are being used. Identifying and using the other person’s sensory language (e.g., replying by using similar words and phrases) increases the likelihood that the individual will perceive that their communication is being heard accurately, which can enhance rapport.

Visual communicators think by creating pictures in their mind’s eye or in hard copy. They tend to use visual metaphors and you may hear words and phrases such as:

Auditory communicators tend to think by creating an internal dialogue. It is important to them to speak well. They tend to use auditory metaphors and you may hear words and phrases such as:

Kinesthetics tend to communicate by getting in touch with what they sense. They may need to move around when communicating and often have a fine use of muscles. They tend to use kinesthetic metaphors and you may hear words and phrase such as:

Sensory preference impacts every facet of life. Here are three examples.

Unless you make a conscious choice to do differently, you tend to communicate with others in your preferred sensory system. When your sensory preference matches theirs or the specific environment you tend to feel accepted, validated, smart, comfortable, and affirmed. When your sensory preference does not match, the opposite can occur.

Differences in sensory preference impact relationships and underlie many communication problems, situational misunderstandings, and feelings of discomfort. Understanding this can alert you to ways in which you can prevent some of these from occurring in the first place and can offer you strategies for resolution when problems already exist.

Communication that acknowledges sensory preference is a learned skill, and you can learn those skills.

“What’s your sensory preference?” She was what the really elderly tend to refer to as a sweet young thing.

I smiled and replied, “My sensory preference is auditory.”

“Well,” she said, settling down in an office chair, “we’re different. I like being different.”

I wondered if she meant she liked being different from me or from some other individual or what, but I didn’t ask.

“I’m writing a paper for school and I need to know several things,” she said, removing a checklist of items from her backpack. “First, tell me how knowing your sensory preference is helpful.”

“I can tell you how identifying my sensory preference has helped me,” I replied. She smiled, nodded, and opened her notebook.

“Knowing that I’m auditory has helped me understand the reason I tend to gravitate toward some environments and avoid others. For example, if I have a choice I always select a restaurant that doesn’t play loud music.”

“Oh,” she said as her pen stopped speeding across the page. “I don’t care about loud music but I absolutely, definitely, totally care about how the restaurant smells. If I detect the odor of cleaning fluids, I’m outta there.”

“It also helps me understand how sometimes I am slower at taking in visual data,” I added, “like finding an item on a bulletin board or tripping over something on the floor.”

“Oh, I get it. They didn’t make any noise so you didn’t hear them,” she said, laughing delightedly at her own wit.

“Yes,” I said, “you are getting it. When I attend a lecture I prefer to have the seminar handout in front of me so I can read and jot down notes and listen at the same time.”

“But reading is visual!” exclaimed the girl.

“Actually, you can read with your eyes or your ears or your fingers,” I said. “Reading and listening are decoded in the same part of the cerebrum.”

“Oh, I didn’t know that,” she said. (I love someone who can be honest.)

“Along that same line,” I continued, “if I must take in data visually or kinesthetically, I know that I will need to pay close attention because the data will be coming to me outside of my preference.”

She continued writing until suddenly her head shot up and she said, “What did you say? I didn’t hear you! Oh, guess I’m not auditory.” We both laughed.

“I’m happy to repeat it, knowing you aren’t an auditory,” I said.

She sighed. “It’s really comfortable knowing you know I’m not auditory. I’m always asking people to repeat things and sometimes they get irritated.”

“I’m able to communicate more effectively with individuals whose sensory preference differs from mine,” I said.”

“So, I need tips to help people increase their skills,” the young woman said, checking off the next item on her list.

“That’s easy,” I replied. “Recently I made a presentation on the sensory systems and provided the audience with a Sensory Preference Assessment and a handout.”

“Great!” she crowed. “Saves me writing! Thank you!”

I handed her a sheet of paper that had the following six tips printed on it:

“I’ve got questions about #3 and #6,” she said, chewing the end of her pencil.

“Okay,” I replied.” Take number three. When I meet someone for the first time I smile (in case they’re visual), shake hands (in case they’re kinesthetic), and repeat their name aloud (in case they’re auditory).

“Got it, got it,” she said. “Now number six.”

“If I am giving a present to a close friend (and I know all their sensory preferences), I would likely give a jar of home-made strawberry jam to the kinesthetic or a fragrance I’m sure they love; an audio book or music CD of a favorite artist to the auditory; and flowers or a gift certificate for a silk scarf to the visual.” I paused. “It took me a bit longer to be gracious and enthusiastic when someone would give me scented bath soap, for example. Now, even if it isn’t an auditory gift, I can feel affirmed by their gesture, knowing they’re giving me something they like based on their sensory preference.”

“Got that, too,” she said. “Boy, I’m going to give a bit more thought to what I give my friends. Thanks.” And she was gone like a small whirlwind.

Sensory Preference Assessment [Adobe Acrobat PDF – 36 KB]

For additional information, refer to Practical Applications and Brain References.

Smell is a potent wizard that transports you across thousands of miles

and all the years you have lived.

—Helen Keller

“No, no, no! Stinky, stinky, stinky!” cried my little brother. Red faced and puffing he tugged frantically at winter clothing that had just been released from their moth ball infested cardboard prison. Watching his discomfort jump-started my interest in the sensory systems, sensory preference, and eventually in synesthesia.

The odor of moth balls didn’t particularly bother me. My brain cringed if a moth ball failed to release itself from my clothing and I accidently sat or stepped on it. Oh my! The sound of crunch was right up there alongside the grating screech of fingernails across a blackboard. (Yes, I grew up with blackboards!)

Not sound, sobs, or odors seemed to bother our mother. How we looked, did. She would calmly continue stuffing us into winter clothing saying, “Well, we wouldn’t want you to go out in public with moth holes in your clothes now would we?” My brother for one certainly didn’t care. Clearly he was more invested in how things smelled. And if he became ill? Oh my! Then, he was beyond sensitive to how things smelled. And there is some anecdotal evidence to suggest that smell may be the first sense to be impacted when a person doesn’t feel well.

Human beings relate with each other, the world, and with nature through the senses. If there is any other way to do so, I don’t know what that would be. Unimpaired, people can use all sensory systems. Typically each will have a sensory preference, although a nonpreferent system may predominate in specific situations.

Sensory preference may be observed from birth or perhaps even before in some (e.g., kinesthetic babies sucking a thumb or finger in utero). Very young kinesthetic children may be seen touching anything that is soft such as the satin border on a blanket and being especially sensitive to the feel of something against their skin and to odors or flavors.

The Smell Survey of1.5 million participants done by the National Geographic Society in 1987 showed that age brought with it little decline in smell ability among respondents. That’s good news since much of taste is contingent on the sense of smell. The study also reported that:

Odors do impact human beings for good, bad, and indifferent. And they’re powerful. Just pay attention to quotes about smell. Here are a few of my favorites:

I like that last one especially. Perhaps because my middle name is Rose (a favorite family name stretching back for several generations on my mother’s side).

And then there’s all the complex routing of the sensory data entering through the brain stem to the correct decoding centers in the cerebrum and in the limbic area. Without the decoding process your brain would be unable to make sense of the sensory data. In that case you might be diagnosed with specific anosmia, the label for a condition described as odor blindness.

As I grew older, I kept looking for information and research related to the sensory systems, sensory preference, and the phenomenon of synesthesia, a condition in which the stimulation of one sense prompts a reaction in another sense. Here are some of the things I discovered.

Olfactory receptor cells—neurons in your nose that allow you to smell—are neurons that can regenerate throughout life. Although these cells are continually being born and dying, they maintain the same connections as their ancestors. The result is that once you learn a smell, it always smells the same to you despite the fact that there are always new neurons smelling it! According to Rita Carter in the book Mapping the Mind, smell is the exception to the brain’s cross-over rule. That is, odors are processed on the same side of the brain as the nostril that senses them.

The work of Bandler and Grinder related to Neurolinguistic Programming or NLP, along with that of others, has added a great deal to the sensory-systems information base and the impact of the senses on communication, learning, and behaviors. In their book Reframing they reported thatdue to the way smells are processed neurologically, they have a much more direct impact on behavior and responses than do other sensory inputs.

Sensory preference was especially fascinating to me. What lay beneath the concept that some types of sensory data appeared to register more quickly and intensely in a person’s brain? There seemed no consensus, however, about the underpinnings of sensory preference. Did triggers involve Epigenetics (cellular memory), heritability, learning, all of these or something else altogether?

Studies by Kaisu Keskitalo and colleagues in Finland has provided data that shines an interesting and potentially helpful light on these questions. According to the researchers, human beings have an innate preference for sweet taste, but the degree of liking for sweet foods varies individually. They decided to study the proportion of inherited sweet taste preference and performed an analysis of a genome-wide linkage to locate the underlying genetic elements in the genome. An article outlining results of their work was published in The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition under the title: “Sweet taste preferences are partly genetically determined: identification of a trait locus on chromosome 16.” This paragraph appeared at the end of the article:

“In conclusion, individual differences in sweet taste preferences appear to be partly heritable. A locus on chromosome 16 was found to affect the use frequency of sweet foods. This result can be considered to be very significant, because a sweet taste preference has not been previously shown to be heritable in humans. This observation broadens our understanding of human food choice. “

If an aspect of kinesthesia (e.g., sweet taste preference) is at least partially heritable, additional studies may reveal that other aspects of sensory preference also have some heritability.

Stay tuned!

And the anecdotal saga of familial sensory preference? My brother, no longer little, continues to be highly sensitive to odors, tastes, and how things feel against his skin. Up until her death, our mother consistently was interested in how things looked. I am aware of sounds usually before any other type of sensory data gets my attention.

Have fun exploring this information. I certainly do!

Note: Multiple resources related to the senses, sensory processing, and sensory preference, are included on my website under Brain References. The Sensory Preference Assessment is available free of charge at arlenetaylor.org.