“We won!” exclaimed Josh, sliding into his chair at the dinner table. “Seven games in a row. I love playing Aussie Rules!”

“You love winning,” said his brother, Ned. “Me? I’m not into competition.”

“I like women’s footy, especially when we ditch keeping score and just have fun figuring out new plays,” said Janet.

“What’s the point of playing if you don’t keep score?” asked Josh. No one answered.

“Four siblings and we’re all so different,” said Gina, Janet’s twin.

“Some brains like competition, others don’t. Some like to play, others prefer to watch,” said their father, helping himself to more mashed potatoes and gravy. “I played footy from the time I could chase a ball. My brother, on the other hand, not so much. Your Uncle Perry would rather work with leather than chase it. Probably the reason he now makes footy gear. And he’s very good at what he does.”

“No chasing leather for me,” said Ned.

“I must have inherited your competitive genes, Dad,” said Josh.

“That, and perhaps cellular memories (epigenetics) from your father’s years of playing,” said their mother. “He had twenty years of footy under his belt before we met, married—and made you.” They all chuckled companionably.

“What makes a person love competition?” asked Gina. “I like to win when we play games during physical education, but never so badly that I try to break the rules or cheat like some do. That makes me very uncomfortable.”

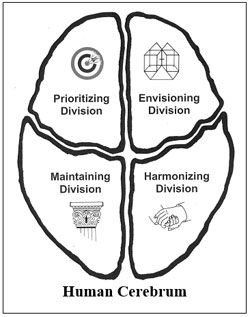

“The love of competition likely has multiple underpinnings,” said their father. “Genetics, epigenetics, opportunities and expectations, perceived rewards, encouragement from family and mentors—and certainly, individual brain differences. For example, an extroverted brain like yours, Josh, thrives on the stimulation competition offers. An energy advantage in the left frontal lobe or prioritizing division of the cerebrum contributes, too, as that part of the brain wants to win. Ned’s brain, on the other hand, leans toward introversion, preferring less stimulation in its environment. His energy advantage is more likely linked with the harmonizing division, concerned with connection, empathy, and helping others.”

“But I’m happy to cheer in the bleachers,” said Ned. “I can actually get quite pumped at times—as long as I’m off the field.” He laughed.

“The testosterone effect,” said their mother. “In addition to surges related to developmental periods, testosterone secretion increases in the presence of any form of competition, including active participation in a competitive situation or virtual participation through observation. Assertive-aggressive behaviors tend to escalate in both genders as testosterone levels rise—although the relative rise appears to be more dramatic in males than in the females. Dr. Michael Gurian points out that although testosterone levels go up with competition in both males and females, males have a much higher testosterone baseline, which makes males on average more aggressively competitive than females.[1] The relationship between testosterone and assertiveness is more complex in females according to Dr. Helen Fisher. Levels of testosterone in females do not appear to rise and fall based on wins or loses in sports as levels do in males.”[2]

“The testosterone effect,” said their mother. “In addition to surges related to developmental periods, testosterone secretion increases in the presence of any form of competition, including active participation in a competitive situation or virtual participation through observation. Assertive-aggressive behaviors tend to escalate in both genders as testosterone levels rise—although the relative rise appears to be more dramatic in males than in the females. Dr. Michael Gurian points out that although testosterone levels go up with competition in both males and females, males have a much higher testosterone baseline, which makes males on average more aggressively competitive than females.[1] The relationship between testosterone and assertiveness is more complex in females according to Dr. Helen Fisher. Levels of testosterone in females do not appear to rise and fall based on wins or loses in sports as levels do in males.”[2]

“The desire for sex arises in the hypothalamus, stimulated by hormones, especially testosterone,” said their father. “And males have 10-20 times more testosterone.[3] Competition raises testosterone levels, rivalry fuels aggression.[4] Since testosterone tends to increase in the presence of competition, dating directly after an exciting competition (e.g., football game, track and field competition) can be a risky affair. In fact, the testosterone phenomenon may play a factor in date rape.”

“I’ll remember that,” said Janet.

“We best all remember that,” said Ned, nodding

“The thrill of competition can increase adrenaline levels in a person’s body, too,” said their father. “As adrenaline levels rise, so does dopamine, the feel-better chemical. Some individuals pursue competition because they are addicted to their own adrenalin and dopamine, released in the presence of competition. That underscores the importance of balance in life. Even a good thing taken to the extreme can result in negative outcomes.”

“So what about our brains?” asked Janet. “Gina’s and mine?”

“My guess is that your brains are probably ambiverted,” said their father, “although there will be differences since every brain on this planet is unique. No two brains are exactly the same and each person’s brain operates most efficiently when involved in activities it does best.[5] You girls each enjoy some stimulation followed by some quiet recovery time. You can compete but don’t particularly gravitate toward it. Janet, your brain’s giftedness may align with the envisioning division that likes innovation, variety, and figuring how to do things in a new way. Gina, your brain may function most energy-efficiently from the maintaining, division because you learn the rules of the game quickly and seem to keep score easily.”

“Is competition good or bad for the brain?” asked Ned.

“Healthy, balanced competition can stimulate brain function and add spice to life,” said their mother. “Taken to the extreme, it can turn everything into a win-lose and sabotage relationships.”

“I know,” said Josh. “Gary practices hard to hone his skills but if the team loses—his dad loses it, too. He berates his son or another player for making mistakes or makes nasty remarks. I feel sorry for Gary.”

“Poor sportsmanship,” said their father. “Learning to reward yourself for doing your very best and yet knowing how to be happy for the winner—even when it isn’t you—are important life lessons.”

“Historically, a male’s sense of self-worth often has come from arenas of combat, where he has struggled on the job ladder, competed in sports, vied in entertainment or fought in politics,” their mother explained. “When cooperating becomes more desirable than competing, some males may perceive their main source of esteem—competition—is undermined. While some female brains like competition, women have generally competed more for male attention than in areas of sports or entertainment. And speaking of brains,” their mother added, smiling, “while all four of you have unique brains, each of you—repeat, each of you—carries their dirty dishes into the kitchen.” They all laughed and began stacking plates.

Different strokes for different folks. Fortunate indeed are those who come from a family system that recognizes, honors, and embraces individual uniqueness, helping each person to hone their brain’s innate giftedness—and thrive.

1 Gurian, Michael, PhD, and et al. Boys and Girls Learn Differently!

2 Fisher, Helen, PhD. The First Sex.

3 Pease, Barbara and Allan. Why Men Don’t Listen and Women Can’t Read Maps.

4 Moir, Anne, and David Jessel. Brain Sex, the Real Difference Between Men & Women.

5 Restak, Richard, MD. Mozart’s Brain and the Fighter Pilot.

Restless with the flight delay, the teenager absently tossed the silver dollar into the air and caught it. I watched as the action was repeated over and over. A split-second distraction and the coin rolled merrily across the floor, its owner in hot pursuit. Victory! But not before several passengers had been jostled, a toddler startled into tears, and a security guard alerted by the confusion.

Returning to the gate area, the teenager was greeted by a parent whose words flew faster than a frog’s tongue: “I told you to be careful with that coin! Why did you do that? What’s wrong with you? Don’t just stand there! Answer me!” Silence. The parent stood with muscles tight, face red, blood pressure building, ready to lose it any second; the teenager with head bowed, shoulders shrugged, and despair etched in every slumped muscle. Talk about a generation gap. Light years apart would be more like it.

Part of me wanted to explain to them that although the child was nearly as tall as the parent the teenager’s brain was still a work in progress, and that this parental style of communication would likely generate more problems that it would solve. But it wasn’t my place and, most likely, my comments wouldn’t have been well received.

Biting my tongue I strolled down the concourse thinking about a discussion I’d had with Dr. Eugene Brewer, Educational Superintendent in Florida. Many people believe that physical maturity equals brain maturity. Nothing could be further from the truth, especially during the first 2-3 decades of life. Just because a teenager’s body appears somewhat adult like, it’s an error in judgment to assume that the same holds true for the brain. Not only that, the brain may not be completely myelinated (the process whereby the nerve pathways are coated with a cholesterol insulation) until somewhere around age twenty or twenty-one, while the prefrontal regions may not be completely developed until mid-twenties or later. A misunderstanding of this mismatch can be a recipe for communication disasters, my definition of generation gap!

Would you believe it? As I reached the end of the concourse a similar situation presented itself. Just different players and a different object. When it got loose the squeegee managed to bounce off at least three passengers, barely missed the reading glasses of a fourth, and finally came to a stop against the traveling cage of a little pup that promptly erupted into frantic yipping. Just what everyone needed in a crowded airport!

With bated breath I waited to see how this parent would respond. No eruption. No pejoratives. Just a few words uttered in a relatively calm voice: “Put the squeegee in your back pack, apologize to the passengers, and then let’s talk about this.” The travelers appeared genuinely surprised by the apology and rushed to offer comments such as, That’s okay, Oh, no harm done, Not to worry, I know it’s tough to hang around the airport.

Curious to hear the remainder of the conversation, I ducked behind an adjacent pillar. “I realize you didn’t mean for the ball to get loose and I know it’s a pain waiting for our delayed flight, especially for someone as active as you are. Nevertheless, [I love that word!] you need to think ahead about the possible consequences of your actions such as a potential for hitting others, breaking reading glasses, upsetting cups of coffee, and so on.”

The teenager nodded and said, “I’m sorry. I didn’t think ahead.” His face held a wan half-smile.

Touching the child’s shoulder gently, the parent replied, “You’ll be more likely to next time. Hmmm. Now, what can you do to pass the time that will have a lower risk for negative consequences?”

How I wanted to shout, Bravo, great role modeling for the next generation! (My Ambiverted brain and a sense of public decorum restrained me.) The parent had identified the problem, gave instructions about behaviors required in consequence of the initial action, explained the need to think ahead about possible negative outcomes, and offered help to come up with a better choice under the present circumstances. All without yelling, demeaning, or shaming. No generation gap here, I thought, at least not in this situation. I’d spoken a trifle too soon as a strident, brittle voice caught my attention.

“So what good do you think that’ll do?” I peaked around the pillar. An elderly woman was addressing the boy’s parent. “You didn’t even make him tell you why he did it?” She shook her head, the muscles of her face wrinkled in a disapproving mask. Oh, oh, I thought to myself. Here it comes. And come it did with a vengeance. For the next few seconds all manner of suggestions poured forth of how she thought the child/parent interaction should have been handled.

I looked at the parent who a moment earlier had appeared calm and confident. Now the body language bespoke discouragement, weariness, and irritation. “We’ve had this discussion before.” The words were softly spoken but carried an underlying tension. “At best, why questions are difficult for adults to answer and almost impossible for teenagers. Why questions just get in the way of communication.” If looks could kill the elderly woman’s eyes might have accomplished the task effortlessly. Before she could reply, the parent continued, “Case in point, if I asked you why you are so upset with the way I just handled things, how would you answer?”

Her response, when it came, was nonverbal. Shoving her nose in the air, she sniffed, turned abruptly on her heel, and headed for the nearest beverage kiosk. There it was. Loud and clear and ugly. Generation gap! Just a different combinations of generations.

Leaving the safety of the pillar, I headed back down the concourse. This time I really had to bite my tongue to keep from saying to the parent, “I truly admire the communication style you exhibited with your son. You avoided why questions!” I’d also been pleased to note that the parent seemed to be quite well informed. Studies have shown that when confronted with a question, especially when in the midst of an emotionally charged situation, individuals tended to access differing portions of the brain based on their ages. Those above age twenty-one tended to access the thinking brain (cerebrum) where functions related to conscious and logical/rational thought processing are housed. Those under the age of twenty-one tended to access portions of the brain sometimes referred to as the emotional brain (e.g., limbic lobe, pain-pleasure center) where there is no conscious thought—but plenty of emotion!

Therefore, when individuals below the age of twenty-one are asked a question such as, “Why did you do that?” they may want to respond and may even try to do so, but their brains may downshift. As a result, they will likely be trying to formulate an answer from the emotional brain and may become defensive or even unable to articulate effectively. This negative outcome can be further compounded if the child or adolescent perceives the situation to be adversarial or stressful. If the adult (so-called) is processing from the thinking brain while the adolescent is processing from the emotional brain, it’s no wonder there can be a disconcerting disconnect.

Many adults agonize over why questions about their own behaviors. How much more those under twenty-one whose brains are “still in the oven,” so to speak! How easy it is to shame others, especially young people, for things that we ourselves find difficult to accomplish.

Back at my gate it was time to board. Soon we were five miles above the earth and I had sufficient food for thought for the entire trip. Fortunately, we can narrow the generation gap.

As the old proverb puts it, a word aptly spoken is like apples of gold in settings of silver.

“Our triplets are due in about five months,” Eva began, smiling. “It appears our whole family will be complete in one pregnancy. Naturally, we’re noticing other young parents, and their parenting styles are all over the proverbial map. We’ve seen everything from completely permissive to Captain-Von-Trapp rigidity.”

“We just spent a weekend at Disneyland,” said her husband Marc, joining the conversation, “and that trip reinforced our need for a few smart parenting tips—sooner rather than later.”

“Disneyland can be a fun vacation,” said the pediatric coach. “As a metaphor for life, however, it describes a mindset of instant gratification, of wanting it all, trying to avoid consequences, and of using plastic and paying later. But when “later” arrives—as it always will—then the shock sets in.”

“Exactly,” said Marc. “We’d like to start out in the best way possible.”

“Perhaps the first thing to remember is that each brain on the planet is different. Your triplets may arrive in this world on the same day, but each will have a unique brain. Pay close attention to the characteristics they exhibit from birth. Give them a range of experiences, always honoring who each is innately.”

“The sensory systems, for example,” said Eva. “Wouldn’t it be fun if one was visual, one auditory, and one kinesthetic?”

“It would,” their coach agreed, “as long as you didn’t expect each to approach life using the same sensory preference.”

“I’m visual,” said Marc, “but my wife is clearly kinesthetic. I see things more quickly, while she is much more sensitive to odors and tastes and the way clothing feels against her skin. If one of the triplets is auditory, we’ve got the senses covered.” They laughed.

“Add to that the possibilities of an extroverted, ambiverted, or introverted preference,” the coach began.

“That’s mindboggling!” exclaimed Eva, interrupting. “I’m ambiverted, while Marc is more introverted. It really would be challenging if we end up with three extroverts.”

Train up children in the way they should go (in keeping with their individual gifts or “bent”) and when they are old they’ll stick with it.

Proverbs 22:6

Amplified Bible

“Appropriate training also means that your chosen job or career path may be inappropriate for your child, no matter how much you love what you do,” the coach continued. “The tasks your brains do energy-efficiently may be energy-exhausting for your children. Help your triplets identify and follow their individual brain’s bent, not yours.”

“I certainly understand that,” said Marc, nodding. “The eldest son in our family for three generations back has always been an accountant. I apprenticed, but absolutely hated it. When I decided to become a teacher, my life got measurably better almost immediately. It took a few years for my parents to agree it was the best choice for my brain. Eventually, my father told me that he had always wanted to be a cook, not an accountant. Imagine that!”

“Do you have some other cautions?” asked Eva.

The coach was happy to provide several.

“I was raised in an orphanage,” said Eva. “The attendants likely did their best, but I missed out on the type of parenting you just described. I’d like to do better for my child. Oops, children. Especially the unconditional love part.”

“Unconditional love is a journey involving a life-long process of learning to let go,” said their coach. “No clinging, playing favorites, living vicariously, or trying to compensate for your child’s unfortunate choices. It never condones or enables bad behaviors, over-functions or under-functions, or nullifies consequences—(i.e., if you do the crime, you do the time)—even as you continue to show love for the person. I often suggest that parents regularly ask themselves a couple of questions:

“I think my parents gave me a good bit of unconditional love,” said Marc, “although the concept is something of an oxymoron. Their love really sustained me the year I spent in the hospital following a serious vehicle accident. Not to forget the subsequent two years in rehab. We want to give that to our triplets.”

“The unconditional love part,” said Eva, laughing. “Not the vehicle accident or the years of rehab.”

“The lagniappe for today—the little something extra—is the value of patience,” said the coach. “Success requires an ability to wait and be productive while you wait. Studies have shown that being grateful and giving thanks can reduce impatience. Living in gratitude can actually help you delay immediate gratification, when doing so can help you eventually achieve a greater reward.”

“Like studying and finishing high school,” said Marc. “Many times I felt like avoiding my homework. Now I’m glad I persisted.”

“I’ve written these tips down,” said Eva. “Can we come back next month and talk more about parenting in a Disneyland world? This was helpful.” Their coach smiled, and the couple left with an appointment card in hand.

Remember, a parent’s role-modeling is more effective than anything he or she will ever say. Parenting in today’s Disneyland world takes

Sooner rather than later! Note: Taylor’s free Sensory Preference and Extroversion-Ambiversion-Introversion Assessments are available at http://arlenetaylor.org/index.php/taylor-s-assessments-resources.html.

It sure beats the old “time out”…

We heard the yelling long before we rounded the corner in the airport. Further down the concourse we soon identified its source. The little girl appeared to be about five or six years old. Brightly colored pink and purple beads adorned her long braids. The colors matched her shoes and stockings. Right now, however, the braids and the shoes and stockings were going up and down in the air as the child jumped energetically.

“I don’t want to take a time out,” yelled the child. “You take a time out. You’ve been mad and yelling all day. And I am really hungry!” The mother’s face said it all—a combination of acknowledgement, embarrassment, fatigue, and frustration.

“Oh my!” exclaimed Louise (my cousin was traveling with me). “I know them! Here, watch my luggage,” and Louise took off down the concourse at a jog. I followed much more slowly. Pulling two roller bags is a challenge at the best of times. I watched as the two women embraced, while the little girl put her arms around my cousin’s waist and hung on for dear life. Both mother and daughter burst into tears.

By the time I arrived with luggage, Louise had shepherded the pair to a more secluded corner of the waiting area and I was introduced to Maybell and her daughter Clarisse. The alarm had failed to go off earlier that morning, which had resulted in a mad dash for the airport. There had been no time for breakfast. No doubt the low blood sugar in both brains had contributed to the stress.

Their flight was being announced and I barely had time to produce a couple of energy bars from my carryon. The tears subsided as the bars began to disappear. “I never liked the term time out, either,” said Louise, as we watched Maybell and Clarisse head down the jetway. They turned and waved, faces wreathed in smiles. “It has such a negative connotation for most people.”

We brainstormed on the flight, trying to come up with a term that would be more positively construed and yet accomplish the same thing. “First, we need to define the purpose for the intervention,” said Louse thoughtfully. “My parents always told me it was so I ‘could think about what I had done wrong.’” She paused. “That never seemed very helpful to me.” In fact, children often stew during a so-called time out and can end up feeling even more frustrated and resentful.

I thought for a moment. “It seems to me that the purpose is really to allow for a few moments of quiet contemplation, to break the stress cycle, and to figure out how one could exhibit a different behavior in the future, should a similar situation arise.”

“Exactly,” said Louise. “So let’s start with magic moment as the label. A moment during which your brain can take a deep breath and magically alter not only the event itself but also your behavior. If it is perceived as less punitive, much of the negative connotation may disappear.” She paused for a moment and then said brightly, “And we can call it M-‘n’-M. Kids will remember that easily!” And so might the adults, I thought to myself.

Louise had a good point. All human beings experience situations of distress at one time or another and handling them effectively appropriately can be challenging for the adults. How much more so for children who may not recognize the stressor or whose brains lack the necessary tools for resolution due to incomplete development.

Louise said she was going to suggest the concept of a magic moment to Maybell when they met again at their monthly reading group. “You can take one any time, anywhere,” she said. “You simply need to decide ahead of time where you will go in your mind’s eye.”

“In my M-‘n’-M, “I said, turning to look at Louise in the seat next to me, “I see myself sitting on the rocky coast on St. George’s Island in Antarctica. I am surrounded by at least three different species of penguins, all strolling unconcernedly around me within arms reach. Talk about a truly magical moment!” We both laughed.

“And parents who think ahead,” said Louise, “potentially can minimize even the need for an M-‘n’-M. For example, if Maybell had packed the night before and included some snacks in her carryon, the alarm fiasco might have had less dramatic consequences.”

It can also be important to talk about the magic moment ahead of time, and explain that it is just three minutes of creative brainstorming in which you identify three things that could be done differently in the future. You can just close your eyes right where you are or, if you can, retreat to a designated spot (e.g., behind the big rubber plant in the corner) for your three-minutes of mind’s eye. When a parent obviously takes time for a magic moment and calmly talks about what could be done differently another time, this role-models the process for the child. You can also use an M-‘n’-M to think ahead about something that is coming up, rather than waiting until the situation arrives to brainstorm.

Louise was really getting into the spirit of our discussion. She looked out of the window at the billowing clouds stretched out endlessly below the plane. “Hmm,” she murmured. “If Maybell had been able to take an M-‘n’-M herself, what she articulated to her daughter might have gone something like this:

“I close my eyes and picture myself standing calmly behind the cascading water at Niagara Falls. I always feel safe there and filled with awe. What are three things I could change? Next time I double-check the alarm clock to prevent being rushed in the morning. I pack our bags the evening before and include snacks in the carryon. If I feel like yelling for you to take a ‘time out,’ I’ll take an M-‘n’-M myself. It only takes three minutes!”

“Niagara Falls?” I asked Louise in amazement. “Have you been there? The roar of the water drowns out everything. It was definitely a magic moment in my life but perhaps not the type we’re discussing here!” Louise had toured behind the falls, as it turned out, and we both laughed at the recollection. I did, however, understand the benefit of rehearsal.

Will taking an M-‘n-M prevent negative outcomes? Sometimes. What it can do is reduce stress by placing a different spin on the process. It’s a way of becoming more emotionally intelligent. Instead of a negative and hated time out with more heat and resentment generated than solutions, a less punitive and more unique M-‘n-M may result in more positive dialogue and constructive prevention strategies. It’s sure worth a try!

Now back to Antarctica for three minutes of recalled awe! I’m taking an M-‘n’-M just because….

randparents are special! I really knew only one of mine, and she changed my life. Whenever I think about Grandma Rose (after whom I was named) a glow of cherished love sweeps over me. I lived with her for three months during my senior year in nursing school. My brain can still offer me exquisite taste memories of her home-baked bread and French style split pea soup!

What was it that made her so special? In a word: acceptance. She had a way of helping me to feel that I was okay with her just as I was at that moment. Even when I exhibited behaviors that she wasn’t wild about, I always felt accepted. She died in 1984 at the age of 88 (way too soon for me), and her nurturing influence in my life lingers like a rare perfume.

Perhaps that’s why I have such a soft spot in my heart for grandparents in general, like the one who stood in the checkout line ahead of me recently. From a brief moment or two of conversation I gleaned that she was buying birthday cards for her twin granddaughters. Her facial expression was a mixture of happiness, sadness, and frustration as she remarked, “Wish I could give them something really nice.”

And then there was the elderly gentleman who was wandering the aisles of Wal-Mart looking to purchase gifts for his grandchildren. “Eleven of ‘em,” he said, “between the ages of three and twenty-three.” He moved on muttering more to himself than to anyone else, “…suitable gifts that I can afford.”

Sometimes grandparents lament that on a fixed income they don’t have much of value to give their grandchildren. Nothing could be further from the truth! Every grandparent can provide a legacy of inestimable value. They can give a gift that keeps on giving.

For example, studies have shown that a healthy balanced sense of self-worth forms one of the foundation blocks for successful living. Self-esteem levels in children are fairly high during grade school but rapidly decline by the time they finish high school. The decline is even more pronounced in girls than in boys. Even when parents understand this typical self-esteem slide, and devote time to this important area of personal growth, grandparents can enhance and facilitate the process. They often have a major impact on the quality of a child’s life.

Grandparenting is both a science and an art. Think of it as a type of generational mentoring. And you don’t even have to be biologically related to your “grandchild”! You can grandparent a child whose own grandparents have died, who live a great distance away, or who are otherwise unable to offer their grandparenting skills.

What can you do specifically? Here are six practical suggestions to assist you with the art and science of grandparenting:

Make comments such as, “You are a unique person and I am so happy you are part of this family.” If the child violates personal or family boundaries, offer course-correction without devaluation. Critique the performance without criticizing the performer. Reward efforts even when outcomes are less than desirable. Help the child to understand the difference between “Oops, I made a mistake,” (one example of healthy shame) versus “I am a mistake” (the quintessential definition of unhealthy shame). If you never had the opportunity to learn about affirmations or sensory preference and consequently were unable to relate to your own children in an optimum manner that matched their innate giftedness, you can certainly study those topics now. You can hone an affirming communication style and nurture your grandchild in his/her sensory preference (e.g., auditory, kinesthetic, visual).

Ask questions such as, “What do you want to be when you grow up?” “Tell me how you feel about war?” “What thoughts do you have about a Higher Power?” “Tell me about your best friend.” Then shut up and listen. I mean clamp your lips together and stay centered on the child without allowing your mind to wander. Listen in an open, encouraging, nonjudgmental way, thus providing an opportunity for the child to verbalize hopes, fears, and feelings in a safe environment.

Tell stories about what it was like when you were a child and when his/her parents were growing up (if you knew them then). Stories are an excellent medium for transmitting health information, generational history, successes, failures, and a whole host of other meaningful experiences that can help the child to feel hopeful about the future and to avoid pitfalls. Explain that daily choices made throughout life influence not only our personal happiness and success¾but family outcomes as well. Make sure they understand that mistakes are just stepping-stones to help us learn how to live life more successfully. Let them see you handle your mistakes appropriately and share with them what you learned in the process.

Relate to the child in a way that makes him/her feel real—a reality as distinct as their fingerprints. Help the child to understand the difference between needs and wants and to learn to prioritize each. Wants (often referred to goals in adulthood) are an important part of life. Without them, the child may be satisfied with the status quo and never become the person he/she was designed to be. Encourage the child to set and achieve realistic goals, and to realize some wants. They are those little extras that add euphoria to life and create pleasant memories that can last a lifetime. Remember that the brain tends to imprint experiences that involve strong emotions, whether they are happy or sad!

Inspire the child to believe he/she can make a difference in this world. When abuse is present in the environment, children tend to grow up unempowered as a consequence of deficient personal boundaries. Be willing to risk speaking out if you suspect physical, mental, emotional, spiritual, or sexual abuse. Grandchildren are fountains from which the next generation springs. You need to do your part to keep the water as pure as possible. Each person lives “downstream” from someone significant in his/her life. Think of your grandchild as living downstream from you. What is the quality of the water when it reaches the child?

Studies have shown that approximately 75% of the message in a two-party communication is conveyed through nonverbal body language. In other words, do as I do is usually far more convincing than do as I say. When you exhibit a high-level-wellness lifestyle, in balance, you show your grandchildren that growing older can be exciting, stimulating, and relatively free from dis-ease. When accidents or illnesses do occur, you can live the 20:80 Rule: it’s not so much what happens to you that matters, as what you think about what happens to you and how you respond.

Can you really make a difference? More than you may know! You can pass on a gift that no one else can give, can help to fill your grandchild’s love cup and thereby, positively influence the future—of your grandchild, of the culture, of the global village. And you can do this without having to spend a penny (of hard, cold cash that is)! You can do this because you are providing quality time and your unique perspective. It’s a gift that only you can give. A gift that will continue through time. Give the gift that keeps on giving. Start now!

STEP 1. I recognize that I have not completed all the developmental tasks of childhood and admit that in my own strength I am powerless to reparent myself successfully.

STEP 2. I believe that a Power greater than myself can restore me to wholeness and enable me to effectively reparent myself.

STEP 3. In this reparenting process, I make a decision to turn my will and my life over to the care of God, as I understand my Higher Power.

STEP 4. I am making a searching and fearless moral inventory of myself, doing family-of-origin work to discover the factors that interfered with the satisfactory completion of some of the development tasks of childhood.

STEP 5. I admit to my Higher Power, to myself, and to another human being the exact nature of the areas in which I need reparenting and am ready to have my Higher Power assist me in this process.

STEP 6. I am entirely ready to have my Higher Power help me to reparent myself and to complete the developmental tasks of childhood that I have not successfully learned.

STEP 7. I humbly ask God to remove my shortcomings and to give me clarity of vision in the reparenting process.

STEP 8. I am making a list of individuals I have harmed because of my immaturity, contributed to by unsatisfactory completion of some of the developmental tasks of childhood, and am willing to make amends.

STEP 9. Wherever and whenever possible, I am making amends to people I have harmed, except when to do so would injure them or others.

STEP 10. I continue to take personal inventory during my reparenting process and promptly admit when I am wrong.

STEP 11. I seek through prayer and meditation to improve my conscious contact with my Higher Power, asking for wisdom and energy to reparent myself toward wholeness.

STEP 12. I am reparenting myself toward wholeness and am sharing my experience with others as appropriate, encouraging them in their recovery and reparenting process even as I practice these principles in my life on a daily basis.

It had been a hectic day. Heather had been up since 4:00 a.m. making lunches, throwing clothes in the washing machine, and leaving breakfast on the table. Promptly at six o’clock she left the house for the outpatient surgery center where she worked four days a week.

Now, back home after her eight-hour shift, Heather glanced at the clock. As wife, parent, nurse, homemaker—you name it—she was accustomed to completing many tasks in the shortest time possible. Once again she filled the washing machine, this time with sheets and towels. Soon it was swishing and spinning its load.

A few adept motions and Heather had her beloved bread machine filled with ingredients for a polenta loaf. She hummed along with the machine’s humming sound and thought about the scent of freshly-baked bread that would soon be filling the kitchen. That triggered the thought of another scent. Cookies! The twins would be home from school in another hour. Time to make a batch of chocolate-chip cookies if I hurry, Heather thought to herself. They’ll top off spaghetti and salad nicely!

Heather was just removing a tray of golden-brown chocolate-chip cookies from the oven as the two eight-year-olds burst in through the back door. “Cookies!” shouted Trevor. “Cookies!” echoed Trisha. “Can we have cookies?” they asked in duet.

“No, you can’t,” replied Heather, placing the hot cookies on wire racks to cool.

“Why not?” asked Trisha.

“Because it would spoil your appetite,” replied Heather.

“No it wouldn’t,” said Trisha.

“Yes, it would,” said her mother.

“It won’t spoil my appetite,” said Trisha. “I had P.E. this afternoon and I’m starving!”

“I said no,” repeated Heather.

“That’s not fair!” said Trevor.

“It is fair because I make the rules,” replied Heather, a note of exasperation creeping into her voice.

“Well, it’s not fair!” said Trevor. “You don’t know what my body wants. I ran around the track this afternoon and I’m starving, too. You’re mean!” and he stalked off to his room, his face a thundercloud.

“Please, Mummie!” begged Trisha. “Just one. I promise I won’t ask for any more before dinner.”

“I said no, Trisha. Why do you keep asking?” asked her mother. “What part of ‘no’ don’t you get?”

Trisha burst into tears. “You could let me have one,” sobbed the little girl. “It wouldn’t hurt you to let me have one!”

“That’s it!” said Heather. “Go to your room and stay there until dinner.”

“Why do I have to go to my room just because I want a cookie?” asked Trisha.

“Because I said so!” shouted Heather. “I’m sick and tired of your begging! I wish I hadn’t even baked cookies!” Heather’s face was red and it wasn’t from the heat of the oven.

Head down, Trisha slowly turned and walked to her room. Even as the door closed behind the child, sounds of her heart-rending sobs could still be heard.

Heather sank into a chair. Well, that went well, she thought to herself. What a dismal atmosphere that interaction created. Indeed, what could have been a happy after-school reunion between parent and children had gone straight to hell in the proverbial hand basket.

Dinner that night was also a rather dismal affair. Trisha’s face was still tear-stained. Trevor’s expression was still disgruntled. Their father asked about how school had gone and received monosyllabic responses. When he asked the reason for their sad faces, the children mumbled something about wanting cookies. “Sure, cookie-time,” their father said, smiling.

Heather brought a plate of golden-brown chocolate-chip cookies to the table and said, “Help yourself to two cookies each.” The twins sat nibbling slowly, in silence. This was not the happy dinner I had in mind, Heather thought. What a disaster!

Later that week, the twins brought home a flier announcing a lecture that was being sponsored by the local PTA. The topic was how to increase compliance and decrease conflict in communicating with children. Heather decided to attend and “had my eyes opened,” as she put it, when recapping the information later that evening for her husband.

There can be a huge difference in the way differing brains absorb and respond to language. The left hemisphere is believed to be home to decision-making as well as Broca’s Area (spoken language) and Wernicke’s Area (decoding heard language). Individuals with an innate energy advantage in the left hemisphere typically know how to spell the word no andthey understand what it means. They may choose to argue, debate, or demand what they want when they want it, but their brains do get the concept of no.

The right hemisphere, on the other hand, is the home of possibilities, the venue for creativity and spontaneous problem-solving. Either it doesn’t understand the word no or its focus is so strongly on how can I make this happen? that it tends to ignore or ride roughshod over the concept of no. Many parents and teachers can tell stories about how exhausting it can be to have a right-brained child come up with every possible option under the sun in an attempt to get a yes response.

“That’s what happened when I made cookies the other night,” Heather told her husband. “Trevor got my no, although he didn’t like it and tried to argue that it wasn’t fair.” Her husband nodded. “Trisha, on the other hand, bent all her energy on trying to get a yes. I see that now and how I played right into the situation.”

“Did the speaker have any suggestions?” asked her husband.

“Sure did,” responded Heather and she went on to describe the discussion and role-playing that had kept the evening lively, interesting, and helpful. “I wrote this down,” explained Heather: Always say yes if you possibly can, even if you need to use a qualifier. I’m going to practice,” she added.

“Hmmm-m-m. Always say yes if you possibly can,” repeated her husband, a twinkle in his eye. “That could be good.” They both laughed.

A couple of weeks later Heather had the opportunity to do some hands-on real-time practicing. On this occasion, Heather’s mother had arrived bearing gifts just before the twins burst in after school. The gifts included three dozen favorite mini-cupcakes, each decorated with frosting and red-hot candy hearts. The twins took one look at the cupcakes, jumped up and down, and cried, “Cupcakes! Cupcakes! Can we have cupcakes?”

Heather had looked at her mother and replied, “Yes, you may have cupcakes in about two hours, at dinner tonight.”

“In two hours?” asked Trevor.

“Yes,” replied his mother.

“Do we have to wait two hours?” asked Trisha.

“Yes,” Heather replied.

The twins looked at each other, a puzzled look on each face. “Can we have two cupcakes?” asked Trevor.

“Yes, when you have eaten all your salad tonight,” replied his mother.

“Can I have four cupcakes?” asked Trisha.

“Yes,” Heather replied. “You may have two cupcakes for dinner tonight and two more cupcakes tomorrow.”

“But I still have to wait ‘til dinner?” asked Trisha.

“Yes,” Heather said, smiling. “Put your books in your room and change your clothes. You can visit with Grandma for awhile before she has to leave to pick up Gramps at the dentist’s office.” The children looked at each other somewhat uncertainly for a moment, and then turned and ran toward their rooms.

“Your face has a deer-in-the-headlights look,” said Heather’s mother. “What’s the deal?”

“The deal,” said Heather, “is that this is the first time I can ever remember saying no and not getting a big argument.”

“But you didn’t say no,” said her mother, her face wreathed in a rather mischievous smile. “You said yes—with a qualifier.”

Heather smiled back. “I did, didn’t I? And the response was light-years ahead of my last confrontation with the twins. Just wait until I tell their father. This is good news!”

And it was.