Tall, dark, and handsome, Wiley Pillar could have been the quintessential poster boy for Gone with the Wind. Along with an aura of contained fury, however, restlessness about his person belayed contentment. His story was all too common in corporate business: the opportunity, rocket growth, an exhilarating ride, an altered lifestyle, and then the crash. Not only had he lost his job and profit from the cooperative venture, he had had to watch a former colleague who “had been a bit cleverer than the rest of us,” continued to float along on a thick cushion of financial security.

“I’m here,” Wiley stated, “because I’m stuck somewhere on Jacob’s Ladder.” My face must have mirrored my confusion because he laughed, a deep, resonate, infectious laugh. “My father was a jazz trumpeter,” he explained, “and he loved that old tune. I must have heard it a million times growing up. Makes a great metaphor.”

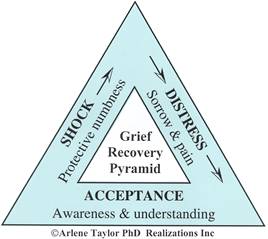

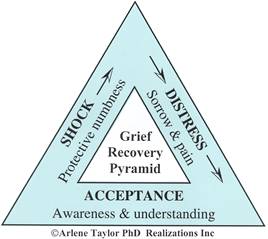

Wiley had read about loss and recovery and had pinpointed his current position on the Grief Recovery Pyramid. “I’m flopping back and forth between distress and acceptance. Like a dying fish,” he said ruefully. “And I can’t find the next rung.”

Loss is part and parcel of being human. Successful recovery doesn’t happen by wishing. It requires awareness, thoughtful effort, and conscious choices—a process that is as unfamiliar to most as a foreign language. There is good news. Recovery is possible, and you don’t have to go it alone. On the other hand, no one can do it for you. “Recovery from your loss is your job,” I told Wiley. “Here are seven steps to consider.”

1. Create a loss history

Get a very large sheet of paper, draw a horizontal line across the center, and create your own personal loss-line. Write down all the losses you can recall, including even what may seem to be small losses. Assign relevant dates and locations to the best of your memory. Write down all the losses you can recall. Include even the little losses, so called. Avoid denial, mislabeling, and minimizing your loss history. Seeing your loss line can provide you with a larger picture and may trigger recall of losses you have not yet even identified, much less grieved. This is important because unresolved emotional pain can be cumulative. An emotional slush fund from the past can increase the intensity of your reaction to present episodes of loss, causing you to react out of proportion to the situation at hand. Some would like to avoid this part of the process, but I encourage them to bite the bullet and do the work. It is worth its weight in gold and can pay huge dividends.

2. Verbalize your loss

Every human being experiences some type of loss in life, so there is no shame involved, unless you decide to assign some. Talk about your loss. Use real words and avoid euphemisms. This may be more of a challenge for the male brain. The female brain’s challenge can be to refrain from endless rehearsal five years down the line. Say aloud that you are engaged in the process of grief recovery. This helps make it real to your brain. Learning how to matter-of-factly state what happened to you can help to get the information out in front of you, which can make it easier to deal with. It can also help you avoid some of the acting-out behaviors that adults tend to exhibit when they don’t know how to else express their emotional pain. Behaviors such as getting drunk, crashing the car, kicking the cat, having an affair, engaging in unprotected sexual activity, sloughing off at work, using drugs, zoning out in front of the television … you name it.

3. Get off the blame merry-go-round

Stop blaming anyone, yourself as well as others. Avoid “what if,” “if only,” “how could they,” and “why me,” or their equivalents. Most people did the best they could at the time with the tools they had. Even if the individuals were evil, it is impossible to go back and alter what happened. Think of blame as the quintessential “red herring.” Blaming takes energy and can derail your recovery process. Dealing with what is can:

4. Take complete responsibility for your recovery process

Remember, no one can do it for you. It involves your loss. Other brains will likely perceive your loss differently from the way your brain perceives it because your brains are different. This includes taking responsibility for allowing yourself to experience all your emotions. They are physiological signals that are designed to get your attention, give you valuable information, and provide energy to take action. You need the information they can provide. Take responsibility for the feelings you create and maintain. Remember that you can change the way you feel when you change the way you think. Take responsibility for any and all actions you take and for all the behaviors you exhibit.

5. Access a support system and accept help

No one is an island. Human beings are relational and spiritual creatures and can provide vital support to each other. Develop relationships with a few key people who can listen to you talk, provide helpful feedback, engage in selected activities with you, or just “be” with you as needed. Avoid a tendency to isolate from others. Allow others to give you the gift of their empathy and caring, and accept their gift, but connect in a balanced manner. Include interaction with pets if they exist; pets can form key elements of your support system. Be very clear with yourself and others that while they may be supportive and affirming, they cannot work the process for you. Hone your spirituality in ways that work for your brain. This may involve meditation, nature, music, the arts, reading, or any of a variety of other meaningful endeavors.

6. Respect the nature of your loss and consciously choose to celebrate

Celebrations can alter your brain’s chemical stew in a positive and hopeful manner. Happiness and thanksgiving can co-exist in the midst of tragedy and loss. Laughter increases the level of several brain chemicals that can help you feel better. Celebrate:

If a death was involved, know that you have the ability to carry a picture of your loved one in your mind. You may want to do something special to help keep the memory of your loved one alive or to memorialize the loss in a beneficial way (e.g., Mothers Against Drunk Drivers).

7. Look for the open door

Recognize that you always get something when you have to give something up. Nothing is ever wasted in the universe. Look for the gift and find that something. When one door closes in life, avoid spending time and energy pounding on it. Instead, look for other options. Be alert to unexpected opportunities and take constructive action to walk through the door that isopen and embrace the opportunity.Something very wonderful may happen in this process if you and your brain and your heart are open to it. Above all, honor your own work in the face of loss, whatever that loss may be—it does involve work!

“That’s all?” Wiley asked when we had discussed the seven strategies.

“There is the matter of forgiveness,” I replied, recalling his comments about thecleverer colleague. I had alluded to the concept when we had talked about giving up blame.

“Are you going to go all metaphysical on me now,” he growled, “just when I was starting to think you know what you’re talking about?” I couldn’t help burst out laughing. “I’ll tell you up front,” he added, his face twisting in a wry smile, “I’m not big on warming a pew every week.”

I explained that forgiveness is a gift you give yourself. It needn’t involve religion or even a deity unless they are already part of one’s belief system. Forgiveness does provide several key benefits, however. It allows the body to turn down the production of cortisol and other harmful substances that can actually destroy brain cells. And while it doesn’t change what happened or make you like what happened, it is a way of releasing destructive feelings that can sap health and diminish happiness.

“Okay,” Wiley replied, still growling. “What does your brand of forgiveness entail?”

My brand is pretty simple. It involves six steps:

My belief is that you forgive or you risk deteriorating your brain and body. Not an attractive picture! Affirmations can be used to instruct your subconscious mind to let go of past pain; to forgive, move forward, and embrace a more positive future.

Wiley knew what had to be done to get to the next rung. And he was willing to do it. As he walked down the hall toward the elevator, I could hear whistling. Jacob’s Ladder. Wiley was climbing.

Waste no time in mindless grieving because it is over—smile and

give thanks because it happened at all!

—Arlene R. Taylor

Loss can be described as the state of being deprived of something that you hoped for or once had or thought you had; the perception of being without something that you valued and wanted to retain. The loss can be physical—you can touch or measure it—or it can be abstract, perceived in cognitive, emotional, philosophical, behavioral, or spiritual dimensions. And often a combination of both. On this planet, there are times when the loss is temporary or can be fixed and repaired. There are also times when it cannot.

Avoid getting caught in the trap of defining loss too narrowly. It could involve the death of a partner, family member, friend, or pet or separation/divorce; displacement due to a natural disaster such an earthquake, hurricane, flood, or tornado; the loss of a body organ or body part; the loss of some sensory perception (e.g., sight or hearing); a hoped-for event that does not materialize or the diminishment of your options (e.g., inability to follow a certain career path). Defining loss more globally can help you to identify it more quickly and begin the process of effective grief recovery in a timely manner.

Creating a Loss Line—hard copy or electronic—can help you picture losses over your lifetime; some of which may be prior to your actual birth. Write the date and the loss event in the middle of the page.

Grief recovery is the process of learning to feel better and to achieve a condition of balance following any type of loss. For some, grief recovery means returning to a previously experienced state of soundness and balance; for others, it means attaining a state of soundness and balance that they may not have experienced before. It involves grieving the loss and healing the pain. Just as human beings can recover from the pain of surgery and feel better as the incision heals or recover from a broken bone and feel better as the bone heals, so you can recover from a loss and feel better as you move through the grieving process effectively.

Grief is something like a toothache. It rarely resolves on its own. Try to ‘stuff’ all thoughts of the loss and avoid grief recovery and you can set yourself up for developing a slush fund of unresolved loss and grief in the brain. This can put you at risk for overreacting when even a small loss occurs down the line and can trigger behaviors that result in negative outcomes (a ‘mess’), which then may require considerable clean-up.

Elizabeth Kubler-Ross discussed the five stages of grief in her book On Death and Dying (1969). The five stages—denial, anger, bargaining, depression, and acceptance—have been landmark in helping individuals prepare for their own death. There can be a vast difference, however, between the grieving process useful in preparation for one’s own death and the grief-recovery process that is effective for survivors of loss.

The Grief Recovery Pyramid is designed to help survivors work through loss episodes and move successfully through the grief recovery process.

Identifying a loss, along with the perception of what it means to you in your life, and the choice to move through the grief recovery process both begin in the brain.

Stages I, II, and III follow, including Suggestions for Action. You may find yourself moving back and forth around the pyramid or even re-experiencing symptoms from time to time.

Stage I -Shock Symptoms may last from a few days to several weeks and may include:

| Suggestions for action Feel and show grief in your own way

|

Stage II – Distress Symptoms may last from a few weeks to two years and may include:

| Suggestions for action

|

Stage III – Acceptance Timelines will vary for each individual.

| Suggestions for action

|

Remember, recovery is a process—an ongoing journey—that differs for each individual because each brain is different. It is what it is and you can do it.

A child can live with anything as long as he or she is told the truth and is allowed to share with loved ones the natural feelings people have when they are suffering.

—Eda LeShan

Loss can be overwhelming for children. They may exhibit this by going from being quiet to noisy (or vice versa), or from caring to aggressive or stoic. They may experience nightmares or sleep-walking, become easily upset, become frantic when care providers are out of sight, or revert to more infantile behaviors (e.g., thumbsucking, bedwetting). To the extent that you are comfortable with your own grief recovery process, you are better able to role model an appropriate process for them. Following are suggestions for helping children deal with loss.

Waste no time in mindless grieving because it is over—smile and

give thanks because it happened at all!

—Arlene R. Taylor

Loss can be described as the state of being deprived of something that you hoped for or once had or thought you had; the perception of being without something that you valued and wanted to retain. The loss can be physical—you can touch or measure it—or it can be abstract, perceived in cognitive, emotional, philosophical, behavioral, or spiritual dimensions. And often a combination of both. On this planet, there are times when the loss is temporary or can be fixed and repaired. There are also times when it cannot.

Avoid getting caught in the trap of defining loss too narrowly. It could involve the death of a partner, family member, friend, or pet or separation/divorce; displacement due to a natural disaster such an earthquake, hurricane, flood, or tornado; the loss of a body organ or body part; the loss of some sensory perception (e.g., sight or hearing); a hoped-for event that does not materialize or the diminishment of your options (e.g., inability to follow a certain career path). Defining loss more globally can help you to identify it more quickly and begin the process of effective grief recovery in a timely manner.

Creating a Loss Line—hard copy or electronic—can help you picture losses over your lifetime; some of which may be prior to your actual birth. Write the date and the loss event in the middle of the page.

Grief recovery is the process of learning to feel better and to achieve a condition of balance following any type of loss. For some, grief recovery means returning to a previously experienced state of soundness and balance; for others, it means attaining a state of soundness and balance that they may not have experienced before. It involves grieving the loss and healing the pain. Just as human beings can recover from the pain of surgery and feel better as the incision heals or recover from a broken bone and feel better as the bone heals, so you can recover from a loss and feel better as you move through the grieving process effectively.

Grief is something like a toothache. It rarely resolves on its own. Try to “stuff” all thoughts of the loss and avoid grief recovery and you can set yourself up for developing a slush fund of unresolved loss and grief in the brain. This can put you at risk for overreacting when even a small loss occurs down the line and can trigger behaviors that result in negative outcomes (a “mess”), which then may require considerable clean-up.

Elizabeth Kubler-Ross discussed the five stages of grief in her book On Death and Dying (1969). The five stages—denial, anger, bargaining, depression, and acceptance—have been landmark in helping individuals prepare for their own death. There can be a vast difference, however, between the grieving process useful in preparation for one’s own death and the grief-recovery process that is effective for survivors of loss.

The Grief Recovery Pyramid is designed to help survivors work through loss episodes and move successfully through the grief recovery process.

Identifying a loss, along with the perception of what it means to you in your life, and the choice to move through the grief recovery process both begin in the brain.

Stages I, II, and III follow, including Suggestions for Action. You may find yourself moving back and forth around the pyramid or even re-experiencing symptoms from time to time.

Stage I -Shock Symptoms may last from a few days to several weeks and may include:

| Suggestions for action:

|

Stage II – Distress Symptoms may last from a few weeks to two years and may include:

| Suggestions for action:

|

Stage III – Acceptance Timelines will vary for each individual.

| Suggestions for action:

|

Remember, recovery is a process—an ongoing journey—that differs for each individual because each brain is different. It is what it is and you can do it.

What we have once enjoyed deeply we can never lose. All that we love deeply becomes a part of us.

―Helen Keller

The friend who can be silent with us in a moment of despair or confusion, who can stay with us in an hour of grief and bereavement, who can tolerate not knowing…

not healing, not curing… that is a friend who cares.

—Henri Nouwen

“Thank you, yes,” said Colleen, when the waiter asked if she wanted her coffee cup refilled.

“No more for me,” said Anita, shaking her head.

The two women had met to talk about how to interact with Jillian, a good friend of theirs who was obviously not present but whose parents had just been killed in a vehicle accident that was not their fault.

“I never seem to know what to say,” Anita exclaimed, sipping coffee. “Afraid I’ll say the wrong thing, I often end up either mumbling some innate platitude or saying nothing. I know the other person senses my discomfort. And it’s really embarrassing when they try to comfort me.” She made a sound halfway between a snort and a moan.

In the words of Meghan O’Rourke:

There is a discomfort that surrounds grief. It makes even the most well-intentioned people unsure of what to say. And so many of the freshly bereaved end up feeling even more alone.

Unfortunately, only too true. As a result, some say nothing—for fear of saying the wrong thing—which can contribute to the freshly bereaved feeling even more isolated. Some say unhelpful things—in a mistaken attempt to be helpful—that only contribute to the freshly bereaved feeling even worse.

“What can I say?” is a common lament on the lips of many, who want to be supportive but have little or no idea of how to go about it.

“For starters,” said Colleen, sipping her steaming brew, “I can tell you what not to say.” She smiled ruefully. “As you know, I also lost both of my parents. For whatever reason, I was closer emotionally to my father than to my mother. For six months I was in so much pain I was dry-eyed. Of course, people didn’t know what to say to me, either—I know that now. However, rather than being comforted, I was often irritated by their comments. No one ever used the word death. Not even the clergyman who did the memorial service. Some launched into a recital of how they felt when one of their loved ones “passed on.” I wasn’t interested in their grief just then. Many of them offered innate platitudes that, while well meaning, were less than comforting. I remember silently creating retorts in my brain and am just glad that my brain filter worked so I didn’t blurt any of them out.”

“Retorts?” asked Anita, genuinely puzzled.

“Yeah, retorts,” said Colleen. “I knew they meant well but I doubt they really thought about what they were saying. I remember going to the grocery store and one clerk saying, Sorry to hear about your dad. Too bad he couldn’t have waited a bit longer to get his one-way ticket punched to the big sleep punched. I tell you: that was unhelpful. For weeks I collected examples of what people said to me. Sometimes I chuckled in private, but for a person in real emotional pain their comments typically were beyond unhelpful and sometimes painful. They sure did nothing to comfort me, that’s for sure.”

“Oh, my goodness,” said Anita. “That is exactly what I want to avoid, which is the reason I sometimes fail to say anything. Give me some more examples and tell me what your ‘silent retorts’ were.” So Colleen did just that.

Anita burst out laughing. “I really regret laughing, Colleen,” she said, “but in a way it’s hysterical and laughter is therapeutic. You could do a whole stand-up comedy routine with those comments. What were they thinking?”

“That’s the point,” said Colleen. “I doubt they were. Thinking. They were uncomfortable and may have felt bad later on, if they even remembered what they said. That’s the problem with platitudes and euphemisms. They often pop out automatically. It would have been more helpful to me if they’d just smiled sympathetically and kept their mouths shut.”

“So, did you ever shed tears for your father’s death?” asked Anita.

“I did,” Colleen replied. “About six months after Dad died, I crossed paths with a colleague whom I’d not seen for several years. When we recognized each other she stopped, put her hand on my arm, and said, ‘I read about your father’s death in the paper and I meant to write you a note because I know how close you were to him. I remember him. He was such a warm, people person. Honestly, I have no idea what you are going through because my father is still alive. Is there anything I can do for you?’”

Anita nodded.

Colleen continued. “I told her that she had just given me a huge gift by her words. ‘I know he loved music,’ my friend had added. ‘I’ll picture him playing his favorite instruments in marvelous venues.’ She smiled and we parted. Driving home I suddenly burst into tears and bawled on and off for two weeks. Her words were so real and authentic; not contrived or trite. They helped me to feel real, to move out of the shock stage, and to embrace the grieving process head on.”

“Wow!” said Anita. “What a difference. Let me put into words what I think happened.”

“It’s almost like a formula,” Anita added. “I know what I can say to Jillian. I can tell her that I remember how I grieved when my mom died unexpectedly. But can only dimly imagine what she must be going through with both parents dying at the same time. In a vehicle accident, no less, that was the other driver’s fault.”

“There’s such a difference between almost brushing off the death as if it were a fly on the table or making fun of it through euphemisms and just calmly stating what is,” said Colleen. “It was a stroke of genius—her giving me a picture of him playing music in marvelous venues, even though that wasn’t his profession. I often see him like that now in my mind’s eye playing his heart out on the violin or the marimba-phone or the alto sax. Such a comforting picture.”

If you know someone who has experienced a loss, be alert and pay attention. You may become aware of their grief through observing changes in their behaviors, especially if they have been unable to verbalize their loss and grief. For example, you may notice that:

You might ask if they want to share what is happening in their life. If they acknowledge loss and grief, ask what they would like you to do for or with them. What they think would be helpful may be light years away from what you expected. One woman asked her friend to accompany her to the mortuary to pick up her loved one’s ashes. If you know them well enough, you may comment on what you notice has changed. Honoring another person includes not trying to push on them what you think would be helpful. They may or may not be willing to talk about them but you have broached the subject and let them know you are interested in their wellbeing. Avoid assuming you know the depth of another’s grief. Ask them to tell you about the person they loved. Telling another person about their loved one can be healing and a way of keeping their memory alive. In some cases, the most helpful thing you can do is just sit quietly with them for a time, sending them loving and positive mental thoughts and not requiring or expecting them to do or say anything.

Remember, grieving with those who have experienced a loss is about them, not about you. Answer their questions if you want to do so, but refrain from talking about yourself and delivering a monologue about “how it worked for me.” That can be deadly not only for grief recovery (because every brain is different) but also for the relationship down the line.

NOTE:

For additional information, refer to Taylor’s website: www.ArleneTaylor.org.

Articles and PowerPoint presentations on the topic of Loss, Grief, Suicide, and Recovery, are available.

The phone was ringing incessantly as I walked into the office. I heard a voice choked with tears. The story emerged in bits and pieces. Aryanne’s brother had been deployed overseas, and the message that all family members hope never arrives—had: Missing in action. Presumed dead. “It’s so sad,” she hiccupped, “even though being in the military was his life goal. How will we ever recover?”

Her reaction was not all that uncommon. Many people are confused about war, to say nothing of never having learned how to truly recover from loss. War and death certainly represent loss, but it can also result from natural disasters, the Chapter 11 collapse of a business with resulting layoffs, or deterioration in one’s health, to name just a few.

As Aryanne sat in my office that afternoon, she felt most insecure about how to help her five-year-old son, Jason. “Several people he knows have been sent overseas,” she said. “And lately he keeps wanting to know…” her voice trailed away.

The question Jason kept asking was, Are you going away, too, Mommy? Because Aryanne didn’t know how to respond, she said nothing, fearing she might make things worse. A child needs explanations appropriate to his/her age level, since too little or too much can exacerbate the situation.

She also reported that Jason had reverted to more infantile behaviors. “He’s back to sucking his thumb and he’s wet the bed several times,” Aryanne explained. “He was way past that before…” Loss can be overwhelming for children, and their behaviors often exhibit this. The child’s stress can be compounded when adults misunderstand these changes in behavior.

Deal with loss effectively can be a challenge. You can make it easier or more difficult for recovery to occur. Here are a baker’s-dozen suggestions for helping children recover from loss.

1. Provide a safe environment in which they can talk about the loss

Listen without judgment to what they think happened. Accept that whatever they perceive is reality for them at this time and refrain from “correcting them” or imposing your brain’s perspective. Be patient. It may be prudent to offer little tidbits of feedback later on, rather than at the moment. It may be helpful for them to talk with someone else near their own age who has experienced a similar loss. The work of children is play. Play with them and listen carefully as they talk to their toys, to each other, and to you. The goal is simply to make it safe and comfortable for them to talk about what happened and how they feel about what happened, without being judged or criticized or corrected.

2. Role model, using words that express emotions or feelings

This can help them become more comfortable with verbalizing words such as:

Also role model using words that express:

Be matter-of-fact about stating your emotions and feelings. They are what they are at that moment. And you have the ability to change the way you feel by changing the way you think.

3. Encourage them to express their feelings in every way possible

The sky is the limit. For example:

4. Be very clear that tears are okay

Not only are they okay, they are part and parcel of how some brains express deep emotion, especially those with an Envisioning brain bent. Tears can be helpful in the grieving process, regardless of gender, but are not necessary for recovery to occur. Avoid encouraging them to cry, but if they do exhibit tears, reaffirm that tears are a natural brain phenomenon and a gesture of deep emotion. Be aware that they may shed tears about something totally unrelated to the loss because of being in a state of sadness. Like referred pain that can move from one location to another in the body, tears related to loss can spring up from unrelated events; events that trigger anxiety or insecurity.

5. Reassure them that you expect to be there to care for them

Remind them of other people in their lives that also expect to be there to help them and to watch them grow up safely (e.g., siblings, aunts, uncles, good friends, and teachers).Tell or read stories about multi-generational events to help them develop a sense of continuity. If it is part of their belief system, comments about a Higher Power can be both comforting and helpful.

6. Give them hope for the future—a vision of what can be

Hang a large calendar on the wall and write down upcoming activities for next week, month, or year. Illustrate them with little stickers or pictures when possible. Refer to these upcoming events as “carrots on the calendar.” Being able to picture upcoming events can help them see past the immediate loss and enable them to imagine the future as a real possibility. They need to experience episodes of happiness even as they move through the recovery process.

7. Maintain familiar routines as much as possible

Knowing what is going to happen can reduce a tendency to carry a sense of uncertainty into every aspect of life. For example:

At the same time, vary the routine occasionally in a conscious and deliberate manner so they don’t get caught in the “I only feel safe when everything stays the same” mentality. If they love “surprises,” vary the routine with a favorite surprise.

8. Encourage them to make decisions

Help them to experience a sense of being in charge of something or in control over something by not only permitting but encouraging them to make decisions. If it is inappropriate for them to be in complete control, at least give them a choice about some aspect of the event, activity, or situation. For example:

Allow them to experience the consequences of their choices. Provide acceptable options and avoid giving the impression by word or gesture thatyou would have made a different choice. That type of response can actually reinforce a sense of inadequacy. The whole purpose of encouraging them to choose is to help them feel safer through being at least partially in control of selected aspects of life. Not only is this helpful during the recovery process, it also gives the brain practice in honing decision-making skills that are critical for success in adulthood

9. Avoid isolating them from the real world

Forget digging a hole and crawling into it. Schedule time with friends and relatives. Reminisce about the happy and the sad. If the loss involves death, exchange stories about the person or pet. Laugh about funny things that happened with them in the past. If tears come, even while you are laughing, accept that joy and loss are part of living. This can increase their sense of safety through continued connection and an acceptance of what is. Role model going with the flow of life. Take steps to make things as smooth as possible, but there are potholes and speed bumps in the road of life about which you can do very little. They watch to see how you handle these.

10. Provide opportunities for them to help others

Balanced caring for others can help to keep the mind and body occupied with something other than the loss, which can assist with recovery. For example:

Removing focus on the loss can give the brain a much-needed break. It can then return to the recovery process with renewed energy and expanded perspective.

11. Include them in your recovery process

Avoid frightening them with your grief and overwhelming them with it. At the same time, include them at an appropriate level as you move through the process. Be authentic. Allow them to see frailty as well as strength; that is the reality of life. They often have a sense about what is “real” and what isn’t, and it can be confusing when what is happening doesn’t appear to be reality. There are no secrets in families. Just situations and events that people try to pretend didn’t happen, sweep under the proverbial rug, minimize by living in denial, alter through lying, or avoid addressing altogether.

12. Help them find the “gift”

As an old proverb puts it, the universe wastes nothing. Water evaporates into the air and returns as rain. Leaves absorb carbon dioxide and release oxygen. And on this planet you generally must give up something to get something. Conversely, you usually get something when you have to give up something. Help them find the “gift”; identify what they get because of the loss (e.g., no longer having to watch a person or pet suffer, time to spend on other activities, a new lesson learned, the opportunity to encounter new people or environments).This may require that you stop banging your head on the closed door. Look for the door that is open and walk through it.

13. Live the 20:80 Rule

The 20:80 Rule, so called, comes from words of wisdom attributed to Epictetus, a 7th Century Philosopher. Approximately 20% of the stress to the brain and body is due to the specific loss or event, while 80% is due to what you think about it. Acknowledge and address the 20% but concentrate on the 80% and help children do the same. The tendency is to do just the opposite. Suddenly life seems consumed with the horrificness of the 20% rather than acknowledging and dealing with it as part of life—but not all of life. Turn this into a game. For every negative that surfaces, challenge them to think of four things for which to be thankful. This can alter brain chemistry in a positive way. It can also help them hone skills of affirmation that are critically important to successful living. If you live the 20:80 Rule there is a good chance the children will learn it, as well.

Several months later, Aryanne and Jason stopped by. He appeared to be happy and well-adjusted. Showing me a picture of a darling little terrier, Jason explained that it was his job to help the little pup be happy. “We play ball,” he said proudly. Aryanne could be proud of the work she had done, too. She had made it easier for recovery to occur.