“We won!” exclaimed Josh, sliding into his chair at the dinner table. “Seven games in a row. I love playing Aussie Rules!”

“You love winning,” said his brother, Ned. “Me? I’m not into competition.”

“I like women’s footy, especially when we ditch keeping score and just have fun figuring out new plays,” said Janet.

“What’s the point of playing if you don’t keep score?” asked Josh. No one answered.

“Four siblings and we’re all so different,” said Gina, Janet’s twin.

“Some brains like competition, others don’t. Some like to play, others prefer to watch,” said their father, helping himself to more mashed potatoes and gravy. “I played footy from the time I could chase a ball. My brother, on the other hand, not so much. Your Uncle Perry would rather work with leather than chase it. Probably the reason he now makes footy gear. And he’s very good at what he does.”

“No chasing leather for me,” said Ned.

“I must have inherited your competitive genes, Dad,” said Josh.

“That, and perhaps cellular memories (epigenetics) from your father’s years of playing,” said their mother. “He had twenty years of footy under his belt before we met, married—and made you.” They all chuckled companionably.

“What makes a person love competition?” asked Gina. “I like to win when we play games during physical education, but never so badly that I try to break the rules or cheat like some do. That makes me very uncomfortable.”

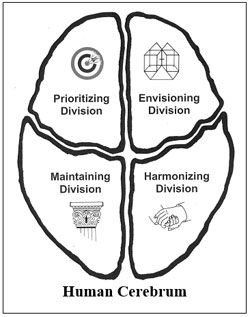

“The love of competition likely has multiple underpinnings,” said their father. “Genetics, epigenetics, opportunities and expectations, perceived rewards, encouragement from family and mentors—and certainly, individual brain differences. For example, an extroverted brain like yours, Josh, thrives on the stimulation competition offers. An energy advantage in the left frontal lobe or prioritizing division of the cerebrum contributes, too, as that part of the brain wants to win. Ned’s brain, on the other hand, leans toward introversion, preferring less stimulation in its environment. His energy advantage is more likely linked with the harmonizing division, concerned with connection, empathy, and helping others.”

“But I’m happy to cheer in the bleachers,” said Ned. “I can actually get quite pumped at times—as long as I’m off the field.” He laughed.

“The testosterone effect,” said their mother. “In addition to surges related to developmental periods, testosterone secretion increases in the presence of any form of competition, including active participation in a competitive situation or virtual participation through observation. Assertive-aggressive behaviors tend to escalate in both genders as testosterone levels rise—although the relative rise appears to be more dramatic in males than in the females. Dr. Michael Gurian points out that although testosterone levels go up with competition in both males and females, males have a much higher testosterone baseline, which makes males on average more aggressively competitive than females.[1] The relationship between testosterone and assertiveness is more complex in females according to Dr. Helen Fisher. Levels of testosterone in females do not appear to rise and fall based on wins or loses in sports as levels do in males.”[2]

“The desire for sex arises in the hypothalamus, stimulated by hormones, especially testosterone,” said their father. “And males have 10-20 times more testosterone.[3] Competition raises testosterone levels, rivalry fuels aggression.[4] Since testosterone tends to increase in the presence of competition, dating directly after an exciting competition (e.g., football game, track and field competition) can be a risky affair. In fact, the testosterone phenomenon may play a factor in date rape.”

“I’ll remember that,” said Janet.

“We best all remember that,” said Ned, nodding

“The thrill of competition can increase adrenaline levels in a person’s body, too,” said their father. “As adrenaline levels rise, so does dopamine, the feel-better chemical. Some individuals pursue competition because they are addicted to their own adrenalin and dopamine, released in the presence of competition. That underscores the importance of balance in life. Even a good thing taken to the extreme can result in negative outcomes.”

“So what about our brains?” asked Janet. “Gina’s and mine?”

“My guess is that your brains are probably ambiverted,” said their father, “although there will be differences since every brain on this planet is unique. No two brains are exactly the same and each person’s brain operates most efficiently when involved in activities it does best.[5] You girls each enjoy some stimulation followed by some quiet recovery time. You can compete but don’t particularly gravitate toward it. Janet, your brain’s giftedness may align with the envisioning division that likes innovation, variety, and figuring how to do things in a new way. Gina, your brain may function most energy-efficiently from the maintaining, division because you learn the rules of the game quickly and seem to keep score easily.”

“Is competition good or bad for the brain?” asked Ned.

“Healthy, balanced competition can stimulate brain function and add spice to life,” said their mother. “Taken to the extreme, it can turn everything into a win-lose and sabotage relationships.”

“I know,” said Josh. “Gary practices hard to hone his skills but if the team loses—his dad loses it, too. He berates his son or another player for making mistakes or makes nasty remarks. I feel sorry for Gary.”

“Poor sportsmanship,” said their father. “Learning to reward yourself for doing your very best and yet knowing how to be happy for the winner—even when it isn’t you—are important life lessons.”

“Historically, a male’s sense of self-worth often has come from arenas of combat, where he has struggled on the job ladder, competed in sports, vied in entertainment or fought in politics,” their mother explained. “When cooperating becomes more desirable than competing, some males may perceive their main source of esteem—competition—is undermined. While some female brains like competition, women have generally competed more for male attention than in areas of sports or entertainment. And speaking of brains,” their mother added, smiling, “while all four of you have unique brains, each of you—repeat, each of you—carries their dirty dishes into the kitchen.” They all laughed and began stacking plates.

Different strokes for different folks. Fortunate indeed are those who come from a family system that recognizes, honors, and embraces individual uniqueness, helping each person to hone their brain’s innate giftedness—and thrive.

1 Gurian, Michael, PhD, and et al. Boys and Girls Learn Differently!

2 Fisher, Helen, PhD. The First Sex.

3 Pease, Barbara and Allan. Why Men Don’t Listen and Women Can’t Read Maps.

4 Moir, Anne, and David Jessel. Brain Sex, the Real Difference Between Men & Women.

5 Restak, Richard, MD. Mozart’s Brain and the Fighter Pilot.

Hickory, dickory, dock, the mouse ran up the clock,

The clock struck one, the mouse ran down, hickory, dickory, dock.

—Old English Nursery Rhyme

“It’s that I don’t get the respect I deserve!” the woman fairly shouted. “And all because of a mouse!” To my listening ear her words sounded like a combination of whining (anger squeezing out of a very small opening) and reactionary self-pity (a behavior that is low on the Emotional Intelligence Continuum). Peralta’s story came tumbling out.

It seems that she had found tell-tale mouse tracks under the kitchen sink. “Mice make me crazy,” she said, waving her arms expressively in the air, “flaming crazy!”

“You found tell-tale mouse tracks?” I asked. “You didn’t even see the mouse run up the clock?” I couldn’t help it. Her story made me think of the old rhyme my brother and I had learned in childhood.

Peralta looked at me for a moment like I was “flaming nuts.” Obviously, my nursery-rhyme memories weren’t ringing any bells. “So in response to a recent television commercial,” she continued, “I bought a better mouse trap at the local hardware store.” Evidently, she had shown the better mouse trap to her husband when he had came home for dinner that evening.

Peralta stood up and walked around my office. Her body fairly vibrated with emotion. “Do you know what he said?” she asked. “Do you?”

I shook my head. Of course I didn’t.

“He picked up the mouse trap and asked, ‘How much did it cost?’ He wanted to know how much it cost!” she exploded. “Isn’t that just like a man? No sensitivity to my fear of mice!” Peralta was on a roll. “I told him,” she continued,” that it was more expensive than cheap wood traps because it was disposable. And besides, it would save a great deal of time, energy, and drama.” She clamped her lips together in a thin line.

I waited. Silence.

“And?” I prompted after more silence.

“He said,” Peralta continued dramatically, crossing her arms and sticking out her chin, “he said, ‘Less drama would be a treat.’” Her face darkened with rage.

“And?” I prompted again, thinking to myself that less drama likely would be a treat.

“That was rude, uncalled for, showed an utter lack of respect for me, his wife . . . and I’ve been mad at him ever since.” Her chin jutted out even further. “We hardly speak.”

“So when did this happen?” I asked.

“Two months ago,” she snapped.

“Two months ago!” Now it was my turn to be astounded. “You’ve wasted time, energy, and drama for two whole months?” I asked. Really, I hadn’t intended to say that but my brain seemed to have had a mind of its own.

“Well, what would you have said?” Peralta demanded.

“I don’t know for sure,” I replied. “At my present state of growth and development, however, I know it would have been quite different from my response thirty or forty years ago.”

“What would you have done thirty or forty years ago?” Peralta asked, her face lighting up with curiosity.

“Honestly?” I asked. Peralta nodded. “I probably wouldn’t have said anything, but I likely would have spun on my heel and left him standing in the kitchen holding the better mouse trap. And I probably wouldn’t have been oozing with conversation for a while either,” I added, chuckling ruefully.

Peralta laughed. “I can just picture that,” she said. “What would you say now?”

“First of all,” I responded, “a tiny creature like a scuttling little mouse might startle me, but I would not be terrified and I wouldn’t waste any energy on drama.”

“What would you have SAID?” Peralta demanded.

“Probably something like this,” I replied:

Don’t tell me you’d miss the drama of having me climb up onto the counter while screaming my lungs out! How could you live without that?

“He probably would have shrugged and replied, You wanna bet? And then both of us would have burst out laughing. And I would have thanked him in advance for handling the trapping.”

Peralta stared at me for a very long time. Finally she said, “You’d have made a JOKE about it?”

“Most likely,” I replied. “Life is far too short to waste any time on needless drama. Especially with interactions that could drive a wedge between partners or friends.”

I shared with Peralta some of the research about how laughter can be used very effectively to defuse tense situations and to help participants put the events into some type of perspective. For example, mirthful laugher has been shown to:

“It’s difficult to remain upset or stay angry at someone with whom you are laughing,” I pointed out.

“Now I feel like a flaming idiot,” said Peralta, looking out the window.

“You’re hardly an idiot,” I replied, “but you must be quite an actress, especially to sustain not speaking to your husband for two months.” I paused for a moment and then asked mischievously, “Do you think he’s been enjoying the silence? Has it been a treat?”

Peralta burst out laughing but quickly sobered as she replied, “Maybe initially, but it’s not been very pleasant around our house.” Again there was silence.

“I’ve been a fool,” the woman said, “but I am a good actress, and I have a great idea.”

“What is it?” I asked (and then quickly wished I hadn’t).

“I know where there’s a costume store,” she began. “I’m going to dress up like a mouse. And when my husband gets home tonight I’ll squeak that I need to be trapped and…”

She had stopped speaking because I had both hands in the air. “Too much information,” I said.

And then we talked about what she could do differently in the future, should a similar situation arise. “That’s how you begin to increase your level of Emotional Intelligence,” I explained. “You replay the video in your head, stopping it when you reach the spot where you’d really like to exhibit a different behavior. You picture yourself doing the new behavior and that gives your brain a new pattern to follow.”

We chatted a while longer, and then Peralta, glancing at her watch, jumped up. “I’m off to get a mouse costume,” she said as the door closed behind her.

Oh, my. Well, whatever it takes, I thought to myself, hickory, dickory dock….