Busting Bad Behaviors

Entering the lobby, I walked straight into high drama. The principle actor was a slim young woman who was fairly vibrating with emotion.

“That’s insulting, demeaning, sexist, racist, and you WILL pay for it!” she screamed, her long ponytail racing in circles. “Who are you to tell me what to do? Who asked you to critique my behaviors anyway?”

Individuals in the group began to drift silently away until only the drama queen was left in the lobby, hands on hips, ponytail still swinging.

Turning to go, she noticed me. Glaring in my direction, she fairly spat out the words: “Did you hear what that b____ said to me? Did you?”

Shook my head.

“Well! She told me I needed to get my s____ together! That’s what! Said I was disgusting, something straight out of the book of bad behaviors for a two-year-old. That’s what!”

I refrained from smiling with difficulty, however, based on the performance I’d just witnessed. It really was Broadway stage quality.

“I expect you’re going to put me down, too! Tell me my behavior was bad, whatever bad means!”

“It’s your behavior; your call. For me, I decide if a behavior is good or bad based on whether the outcome is negative or positive. What I can say is this: that was an Oscar-winning performance.”

“I suppose, if you were me, you’d have done something entirely different,” she said, sarcastically.

“If I were you, I probably would have done exactly what you did. I imagine you were doing the best you could at the time with what you know. Most people do. But if it were myself, I’d probably try to figure out what triggered the comment. And, if I could learn anything from it. Those two things—before I reacted.”

“You are pathetic!” was her response, although her posture relaxed ever so slightly, and her hands fell from her hips. “What could I possible learn from it?”

“What would have been your response if the comment had been “Grow up,” or “Get your life together”? I countered.

“Easy,” she replied. “I’d just have flipped her the bird and told her that I am grown up!”

“And?” I persisted.

“Oh, that I am getting my life together. Well, as soon as I figure out how to do that, I suppose.” She was mumbling.

“She didn’t say either of those things,” I said. “Rather, she gave you a metaphor, which certainly got your attention.” No matter that the language was rather primitive, I thought.

Walking over to a comfortable chair, I removed my coat, sat down, and pointed to a nearby chair. The young woman strolled over nonchalantly and flopped down, legs hanging over one upholstered arm.

“She got my attention, that’s for sure,” she said. “What’s a metaphor?”

“A metaphor is a type of story that can help people better understand a specific situation in their lives by comparing it with something else. Here’s an example.”

“Scruffy is a large loveable hound that lives down the block. Unkempt and ungroomed, he is completely untrained. Wait. I take that back. He has learning that anything and everything goes. His owners, to all appearances, have devoted zero time and energy to teaching this rather loveable pooch how to be a valued member of society. Consequently, he runs wild in his corner of the world: flattening freshly planted flowers, scratching paint off fences and doors, peeing on gate posts, digging holes in gardens, and leaving messes anywhere and everywhere without regard to where people walk or sit. Naturally, he saunters off expecting others to clean up after him. He jumps on people he likes, planting big paws on shoulders and leaving imprints on suits and blouses the size of a saucer. He can do in a pair of glasses with one swipe of his big tongue. Most regard him as an unmitigated neighborhood nuisance. But because they like his owners, they tolerate his egregious behaviors—so far, anyway.”

“I can picture that,” she said, actually smiling. “Why doesn’t someone just bust the hound? I’d do it if I lived in that neighborhood.”

It was my turn to laugh. “How might this metaphor apply to your life?” I asked.

She shrugged, rolling her large dark eyes expressively. “I’m sure and certain you’re about to tell me!”

“Only if you want to hear my brain’s perspective.

She shrugged and assumed a regular sitting position. I took that as a go-ahead.

“Compare yourself to Scruffy, although you are much better looking.” She chuckled. “Although I have no idea what triggered that other person’s comments, is there any possibility that you’ve been making messes in your corner of the world and expecting others to either pick up after you or live with it? Any chance you have been exhibiting JOT behaviors—that is, J-jumping to conclusions, O-overreacting, and T-taking things personally? If so, have these resulted in positive outcomes for you?”

“Boy, you don’t pull any punches!” the young woman snapped. After staring at the floor for a few minutes, she got up, walked back and forth a few times, and then settled back down in the chair, legs over the arm again.

Finally looking up with tears glistening in her dark eyes, she said, “Okay, I get it. But only because of your meta-something.”

“Metaphor,” I repeated.

“But I still don’t like being told to get my…” I held up my hand, signaling that I remembered.

“Whenever another brain shares its opinion, you always have a choice,” I said. “You can choose to jump to conclusions, overreact, and take it personally. Or you can realize it’s just that brain’s opinion. You can pick it up and run with it—or not. Learn from it—or not.”

“Oh. Oh,” she said slowly. “I assumed she was intending to put me down. I took it personally and decided she hates me.”

I said nothing.

She sighed. “I might have over-reacted¾just a bit, you understand.” Her face unfolded into a beautiful smile. “Instead of biting her head off, I could have busted my own bad behavior.”

We both burst out laughing.

I gave her a thumbs up. “Good on you, as they say down under. That’s how you start raising your Emotional Intelligence, your EQ. Next time, in a similar situation, you can choose to respond more effectively.”

“Scruffy is in training!” she said, wryly. After a moment of silence, she added, “Were you serious about my performance being Oscar-winning?”

So, she had heard my comment.

“If Oscars were awarded for bad behaviors that result in negative consequences, you bet,” I said, thinking to myself that sometimes they may be.

“I’ve always dreamed of acting on stage or even being a drama coach,” she said wistfully.

“Then go for it,” I replied. “Harness some of that innate ability and put it to good use. If your brain can perceive it, you can achieve it!”

“You think I could do that?”

“It doesn’t matter what I think. It’s what you and your brain think. If you think you can or you think you can’t, either way you’re right. If today was any indication…” I let my voice trail off.

She looked at me for a long moment.

“Yes,” she said, a new note in her voice. “Yes! Definitely. I can do that! Matter of fact, I am doing it. I’ll invite you to the first play I act in or coach!”

“Deal,” I said.

Jumping up, she pulled me out of my chair, threw her arms around me, and lifted me off the floor by at least twelve inches. Goodness! The woman is tall and strong!

Setting me down after kissing me soundly on both cheeks, she jogged across the lobby and headed down the long corridor, her ponytail making those interesting circles.

Her words drifted back to me. “No more making messes. Bust those bad behaviors instead!”

Retrieving a shoe and putting myself back together, it took me a full minute to stop laughing.

Even more fun than winning an Oscar is helping people bust bad behaviors and make better choices…in their “corner of the world.”

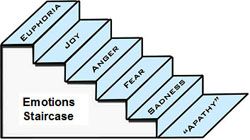

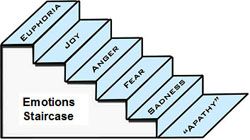

Emotions Staircase

“That does it!” Lars was in full roar. Greta had failed to stop for gas on her way home which, admittedly, was unhelpful. But so was Lars’s ranting, raving, and flailing of long arms that put at risk anyone within reaching distance.

Greta placed her hands over her ears and burst into tears. This, too, was unhelpful, but lived up to their typical pattern. Lars would get frustrated and exercise his lungs, Greta would get flustered and exercise her tear ducts.

“Heaven help us!” exclaimed Great-Uncle Johan, still spry at 89. “The car…it needs some gas. So, fill ‘er up!”

“Greta should have!” Lars bellowed.

“So, send her now,” Great-Uncle Johan said, adding, “She’s seventeen? Maybe still some child. She’ll learn.” Silence. He turned to Greta. “So, this is so bad you have tears?”

“When Lars yells I cry….” Greta’s voice trailed off.

“So, he makes the huge noise like a bull elephant and you cry! Your eyes―they are connected to your ears?” Great-Uncle Johan raised an eyebrow and a shoulder.

“I don’t have time for this nonsense,” Lars began.

“Nonsense for sure,” Great-Uncle Johan agreed, interrupting. “So, you vant to spend your energy in tears?” He looked over at Greta, sniffing and wiping her eyes.

Then he turned to Lars. “So, you vant to spend your energy in loud?” Lars appeared a trifle uncertain, opened his mouth, and shut it again. “Look at your vatch, man,” Great-Uncle Johan directed. “Pick some time. How long you vant to waste on the angry?”

Lars looked at Great-Uncle Johan, then at Greta, and finally at his Rolex. “Two minutes,” he replied after a pregnant pause. He was beginning to feel slightly foolish. The situation seemed both ludicrous and ridiculous, and at this point he was having difficulty keeping his face straight.

“So, be you livid for two minutes!” ordered Great-Uncle Johan. “Go outside. Valk. Den Greta to get gas!” He turned to leave the room, shaking his head and muttering, “Big vaste of energy…all dis yelling and crying! BIG vaste of energy…!”

Lars and Greta looked at each other for a moment and then burst out laughing.

* * * * *

Great-Uncle Johan was right. Many people expend vast amounts of energy yelling and crying, often over a little blip on the screen of life. When negative behavioral patterns continue year after year, it’s like they are suffering from The Ostrich Syndrome: their heads stuck in the proverbial sand box, at least in terms of managing their emotions and feelings.

Not only do humans vary tremendously in their perception of emotions but also in their ability to identify, articulate, and manage them effectively—a challenge that ranks right up there in everyday living. Although the words emotions and feelings are frequently used interchangeably, they are notsynonyms in terms of brain-function. They even follow different pathways in the human brain!

Emotions are physiological changes that occur in response to an external stimulus or an internal one (such as a thought). They function as cellular signals designed to get one’s attention much as an orange highway flag is designed to alert a driver to a situation up ahead. When in the grip of a strong emotion, the human brain is in a biochemically altered state that comes complete with distinctive facial expressions, physiological markers, gestures, and actions. Candace Pert, the researcher who first identified opiate receptors in the human brain and was interviewed in the documentary What the Bleep? pointed out that each core emotion may relate to a specific neuropeptide, a brain chemical that influences mood.

Although beliefs differ regarding the number of “core” emotions, scientific evidence exists that facial expressions registering Joy, Anger, Fear, and Sadness are inborn and can be observed on the face of a fetus during gestation. Although there are hundreds of words related to emotions, likely they could be assigned to one of these four. Emotions translate information from the subconscious into conscious awareness and provide energy for constructive action. In this sense, all emotions are positive—although the actions exhibited around them may be negative.

Feelings, on the other hand, reflect one’s subjective interpretation as the brain tries to make sense of the physiological changes that result from the emotion. Human beings create their own feelings based on experience, learned behaviors, personal belief systems, and thought patterns―to name just a few. It’s empowering to realize that no one can force you to maintain a specific feeling over time. Others can provide a stimulus that triggers an emotion. But you take it from there in terms of feelings and behaviors.

This means that, while you may not be responsible for every emotion that surfaces, generally you are responsible for the feelings you choose to maintain (i.e., you create your feelings by your thoughts) and the behaviors you choose to exhibit.

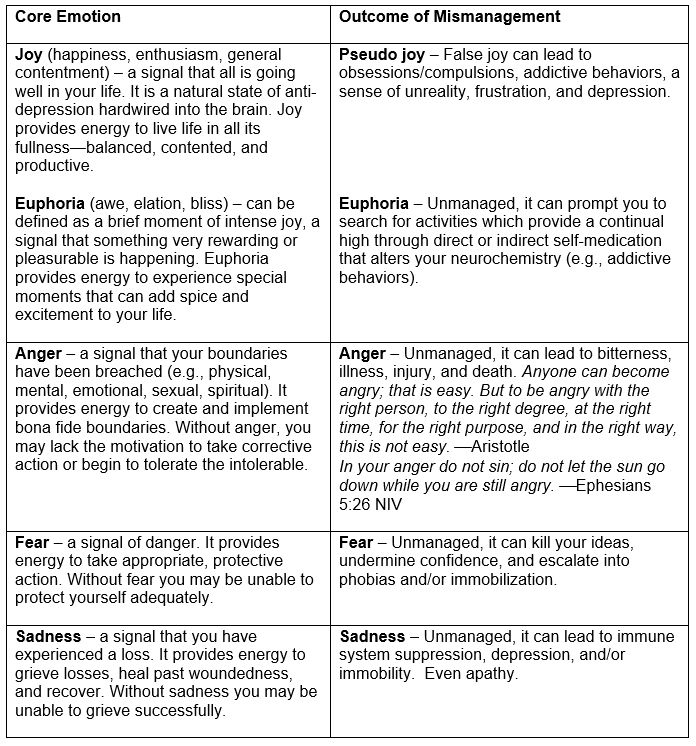

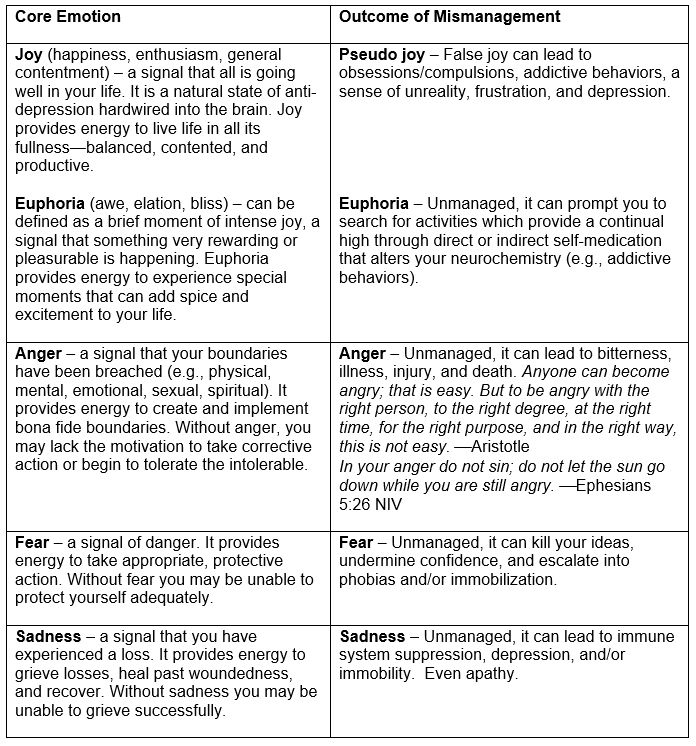

The following table lists core emotions, along with a summary of their purpose, and examples of undesirable outcomes that can result from mismanagement.

Rather than being labeled as “core” emotions, surprise, disgust, shame, and guilt are often referred to differently. Surprise and disgust are emotional motivators that can arise in combination with a core emotion. Surprise can surface in combination with any core emotion; disgust, often in combination with anger, fear, and sadness.

Shame and guilt are learned reactions that serve as interrupters to remind you of your human limitations. It can be difficult to differentiate between the two.

- Healthy shame says, Oops, I made a mistake! I can learn a more functional behavior and make a different choice in the future. Healthy guilt can motivate you toward constructive action when you have violated personal values or standards. Contrition is sometimes used as a synonym for healthy guilt. Contrition involves some remorse for having made a mistake, along with accepting some responsibility for the mistake or, at least, for your part in the situation. Neither healthy guilt nor contrition endlessly beats one up for being human.

- False shame says, What a putz! You are so inadequate. You deserve to be punished. Rather than simply admitting that you are human and made a mistake and are capable of course correcting, false guilt tries to instill a belief that you yourself are a mistake.

The Emotions Staircase portrays core emotions as a series of steps. Metaphorically, you will be standing on one of the steps at any given moment. With increased awareness of your own emotions and by implementing strategies for managing them more effectively, you can learn to spend most of your time on the step of Joy and typically move to another step only when the present situation warrants it. While not thought to be an emotion in and of itself, Apathy may represent a state of being emotional overwhelmed in which the individual becomes immobile. Human beings rarely try to commit suicide when in a state of apathy. They don’t have the energy! They can be at higher risk for suicide attempts as they begin to move back up the Emotions Staircase and get more energy.

The Emotions Staircase portrays core emotions as a series of steps. Metaphorically, you will be standing on one of the steps at any given moment. With increased awareness of your own emotions and by implementing strategies for managing them more effectively, you can learn to spend most of your time on the step of Joy and typically move to another step only when the present situation warrants it. While not thought to be an emotion in and of itself, Apathy may represent a state of being emotional overwhelmed in which the individual becomes immobile. Human beings rarely try to commit suicide when in a state of apathy. They don’t have the energy! They can be at higher risk for suicide attempts as they begin to move back up the Emotions Staircase and get more energy.

Walking up the down staircase (as some term it) is a learned skill. Where it used to take days or months for some to recognize and resolve a protective emotion (e.g., Anger, Fear, or Sadness), it is possible to develop skills that enable you to walk back up the stairs to Joy in a matter of minutes or hours.

Following is an example of one way to use the Emotions Staircase to avoid taking things personally, spending needless energy because of another brain’s opinion, or becoming defensive. Here’s how one woman described the process.

Imagine a person approached me at a meeting with this comment: “The clothes you’re wearing don’t suit you.” The first thing I remind myself is this: although human brains—as members of the same species—are more alike than different, every brain is believed to differ in structure, function, and perception. Furthermore, all any brain has is its own opinion. Since my mind is very clear about this, rather than becoming defensive or overreacting, I begin to brainstorm possible reasons for a seminar participant to make a comment such as this to the presenter.

Since thoughts can fly across neuron pathways at rates of 400 feet per second, my brain suggests some possible scenarios:

- Sensory preference (e.g., This person, if kinesthetic, doesn’t perceive the fabric is comfortable. Or, if visual, doesn’t like the color or cut. Or, if auditory dislikes the sound the fabric makes.)

- Level of fatigue (e.g., The individual may be short of sleep, resulting in less brain energy for monitoring comments before choosing to verbalize them.

- Seminar topic (e.g., The content is triggering some painful memories in the participant and, since the reason is never the reason, the discomfort is being expressed in criticism of the speaker.)

- None of the above (e.g., The person is simply having a bad day or was dragged along to the seminar and would rather be somewhere else, resulting in negative comments.)

If I want to know more about the seminar participant’s opinion, I can say, “Please be more specific.” If not, I can respond with, “Thank you for sharing your opinion,” and move on to another topic or return to the business at hand.

At my first opportunity, however, I will take a brief inventory. If there has been no negative impact to my brain, I remain at a position of Joy, understanding that the unsolicited opinion reflects that brain’s perception only and may have little (if anything) to do with my reality and the way my brain perceives.

If my brief inventory reveals that I am no longer at a position of Joy―that the comment did impact my brain negatively―then I need to take conscious action to resolve that negative impact. After all, every thought I think affects every cell in my brain and body.

Below is the typical self-talk process I would use to manage that comment and mentally reposition myself at the step of Joy on the metaphorical Emotions Staircase Model:

- Question: What step am I standing on?

- Answer: At Sadness. That’s appropriate to the sense of “loss” at failing to make a good impression on this participant. Remember, however, that only I can decide how much energy I choose to put into another brain’s opinion.

- Question: What factors can I identify that moved my brain to Sadness?

- Answer: My brain connected the participant’s comment to an event during childhood when I was wearing a homemade, rather shapeless, flour-sack dress. As compared to other children, I had felt inadequate, self-conscious, and ashamed of my appearance. Some old self-esteem issues resurfaced that prompted me to wonder if I even know what looks good on me. (My sensory preference is auditory; visual, my lowest.) Also, there were remnants of unrealistic expectations that, by trying hard enough, I can make a positive impression on everyone. Impossible. Wishful thinking.

- Question: Is there anything concrete I can do, or want to do, about that brain’s perception?

- Answer: Not now. That brain’s opinion is none of my business unless I choose to take it personally. I like what I’m wearing. It meets my preferences and is comfortable. I take a deep breath and, using the energy generated by the emotion of Sadness, move to the step of Fear.

- Question: What am I afraid of?

- Answer: Feelings of discomfort, anxiety, or inadequacy. Perhaps sometime another individual will make a similar comment, and my brain will connect it to past experiences. Then, I’ll feel Sad again. I can’t guarantee that won’t happen. However, I remind myself that I am an adult, I can take care of myself, and I know how to implement appropriate boundaries. I take a deep breath and, using the energy generated by the emotion of Fear, move to the step of Anger.

- Question: What am I angry about?

- Answer: That someone (who, in my brain’s opinion, didn’t exactly look like she had just stepped off a Chanel or Dior runway) had made a judgment about what I wore. What flaming nerve! I can’t be accountable for another brain’s perception or criticism. I remind myself that each brain is different and start chuckling at the audacity. I take a deep breath and, using the energy generated by the emotion of Anger, step up to Joy.

- Question: What was the gift in this experience?

- Answer: More practice making a quick return to Joy. Validation that I have the tools to deal with negative/judgmental comments―and that those tools work. I choose how I want to respond. Gratification that I was able to quickly contract with my brain to process the comment later and avoid allowing it to interfere with my presentation.

Good example. Obviously, it takes much longer to write this all down compared to the relatively short time required to go through the self-talk process. You need to develop your own style, recognizing that you pass through each emotion going both ways. However, during the actual event everything usually happens so quickly that you aren’t aware of this. Your goal is to move to the step appropriate for the situation at hand. Then, take the necessary steps to return to a position of Joy.

The following four steps will put you in a much better position to make conscious choices about the way you want to manage your emotions and feelings, the actions you decide to take, and the behaviors you choose to exhibit:

- Identify your emotional history, including the emotional atmosphere(s) you experienced during childhood and adolescence

- Differentiate between emotions and feelings, theoretically and practically

- Understand the factors that have contributed to your present emotional tone

- Work on developing high levels of emotional intelligence of EQ to help you manage your emotions and feelings successfully―hopefully your emotional age matches or exceeds your chronological age.

You can learn to identify your emotions accurately and recognize the information they provide. Then, take responsibility for the feelings you maintain and the actions you take related to them. (Sometimes the appropriate action is to do nothing—at that moment.)

You can hone the skill of processing an event with an emotional component (especially one that involves an overreaction) quickly and consciously. As your skill level increases and you learn to talk yourself through the process of living at Joy, you can role model for others and even teach the strategies to young children.

As Great-Uncle Johan would say, “Vat a deal!”

Fer-de-lance Fiasco

The Constitution only guarantees the American people the right to pursue happiness. You have to catch it yourself.

—Benjamin Franklin

Perched on the stool, her body language screaming dejection, disappointment, and disbelief, she wailed, “I can’t believe I did it again! I keep jumping to conclusions, overreacting, and taking things personally.” She covered her face with her hands.

JOT behaviors, I thought to myself. Off and on over the past ten years, Angie had dropped by to chat. It was usually to rehearse another installment in the on-going saga of her life. Typically, the same chapter, same verse―with just a twist in the details.

“Are you here to tell me about the latest fiasco?” I asked. Angie nodded. Soon it all came tumbling out.

Chad called me late afternoon yesterday and suggested we meet for dinner at a new restaurant in town. As soon as we’d placed our order, we started talking about our upcoming trip to Thailand. I told him how excited I was and said, “After our trip to Cambodia, I think I’ll be a bit more adventurous in trying new foods.”

Chad smiled and said, “I bet we can find you some filet of fer-de-lance.”

I didn’t find that funny, so I clammed up the rest of the evening. It really was very uncomfortable.

Angie stopped her rehearsal and looked at the floor.

“And?” I prompted.

“And I did a similar thing last week when he took me out for lunch. And again the week before that. And a week before that. I tell you: it’s no fun! I’m 47 years old, for heaven’s sake! When am I going to stop?”

“I have no idea,” I said, calmly.

Ignoring my comment, Angie continued. “If I were Chad, I’d probably stop taking me out.”

“Many men would,” I replied. “It can’t be much fun for him either.”

Again Angie ignored my comment. “When I think about it now,” she continued, “it was a really clever comment. I mean, I know what a fer-de-lance is. I read about it in one of the Nero Wolf books. You know, the series by Rex Stout.”

I nodded.

“I think the venom only comes out through the hollow fangs,” said Angie. “It isn’t in muscle tissue, which is the reason snake is on the menu in many Asian countries…”

I nodded again.

“What would you have done in my place?” asked Angie.

“If I were you, probably exactly what you did,” I said, smiling. “Most people do about the best they can at the time with what they know.”

“But what would you have done in a similar situation if you were you?” Angie asked.

“I would have implemented AAA replacement behaviors. Likely have laughed and replied, ‘Very clever! Fer-de-lance! But I said a ‘bit more adventurous’―not off the charts dramatically exotic!’ And, anyway, to me adventurous never includes eating something that ever had a mother―or a face.”

“Well, that’s not what I did,” said Angie. “I pouted, clamed up, and pouted some more.”

“An adult pout is really a quiet, emotional tantrum,” I said.

“Remind me of the AAA replacement behaviors.”

I did:

- First, ASK questions to clarify the situation instead of jumping to conclusions and making assumptions that may be off base and way out in left field.

- Next, ACT calmly as you assess the situation to prevent a reactive emotional tsunami from blowing up a relationship bridge.

- Third, ALTER your perception or reframe the event, looking at it from a different perspective to avoid taking things personally.

“I must be getting something out of this, or I would not be repeating the behaviors.”

“And that would be?”

“I get letting him know I didn’t like what he said. Then I feel sorry for myself because I’m unhappy. And then I get mad at myself for ruining the event. Then I don’t sleep well and wake up with another migraine. And, sadly, I repeat it a few days later…” Angie paused and then said abruptly, “You know, I’m getting really tired of this!”

“Not tired enough,” I said, laughing. “At least not tired enough to put in the work to raise your level of emotional intelligence―your EQ―and choose to exhibit different behaviors.”

“Help me analyze this,” she said. I agreed to do my best.

“Chad’s comment likely reflected male humor, and you completely missed it.” Angie nodded. “Women who fail to understand male humor miss a ton of opportunities for laughter. Males are actually very funny. In some studies they came across five times funnier than females. Knowing that, I always choose to think humor first. They tend to use humor to connect with others and can be great teasers, especially with people they care about.”

“But what if it wasn’t meant to be humorous?” said Angie.

“Then it was just that other brain’s opinion, and I can choose whether or not to pick it up. Personally, I am at a loss to think of even one reason to pick up another brain’s unkind or negative opinion.”

Angie smiled, and we went on to talk about other things to address.

When you choose to take something personally, your brain goes into a “poor me” stance. Feeling anxious and uncomfortable might trigger your brain to downshift into the emotionally reactive mammalian layer and to leap to a very erroneous conclusion. In Angie’s case she might have thought, Well, you nerd! A fer-de-lance is a poisonous snake. You want me to eat a poisonous snake? The nerve!

Or your brain might slide down into the basic reptilian layer where stress responses are housed: fight-flight, tend-befriend, conserve-withdraw. Metaphorically, Angie chose conserve-withdraw and disconnected from communicating with Chad, ruining the evening for them both quite unnecessarily. And, in the process, interfering with a good night’s sleep, suppressing her immune system, and contributing to a migraine.

But that’s not all. Because the brain seeks congruence, it begins to recall other “poor me” incidentsfrom the past. Soon, you feel tired and sad as accumulated injustices come to mind. Enters: an overreaction―which is never just about the present and always about the past to the tune of something like 70 percent. Something about the present reminds your brain of something from the past, bringing back all the unresolved emotional pain and dumping it into the present moment. This often emotionally beats up the other person, who really doesn’t even know about all the unresolved issues in your past.

An overreaction is a behavioral way of saying that what happened to you in the past was unfair. (It probably was and typically requires going through a recovery process to forgive, heal, and move on to high-level-healthiness.) When you over-react, you usually begin to feel indignant about all the accumulated injustices your brain has recalled. As indignation rises, so does the emotion of anger, triggering the release of adrenalin, which gives you a boost of needed energy.

As adrenalin rises, so does dopamine (the “feel better” chemical), which may make you feel better momentarily. Soon, however, you realize that—oh no!―you did it again and start beating yourself up for taking things personally or jumping to conclusions or overreacting, which triggers the release of adrenalin. And so on.

It becomes a vicious circle because—in effect―you have become addicted to your own adrenalin and dopamine. No, you’re not ingesting anything from the outside. You just trigger their release from your own internal pharmacy through the thoughts you think, the feelings you hang on to, and the behaviors you exhibit.

There are consequences, however. Disruption of sleep, nightmares, headaches, and suppressed immune function come to mind, all leading to an increased susceptibility to colds, flu, and other illnesses, and possible adrenal insufficiency as those critical glands become exhausted from the never-ending demand for more adrenalin.

During our discussion of this ugly cycle, some of the color drained from Angie’s face. “I was miserable as a child,” she said, quietly. “I’ve never been happy. I don’t think I know how to be happy. I do know how to take things personally and create a state of chaos—sometimes inside my own head―maybe to get adrenalin.”

“That’s very honest,” I said, “and I’m proud of you. You can only deal with what you can label and describe. And you just labeled and described a bottom line from your childhood: unhappiness.” Unfortunately, unhappiness can become a way of life. Over time, it can turn into a habit.

Happiness is a choice—at least in adulthood. Many people have everything they need (not necessarily everything they want) and could be happy. Yet, they choose to be unhappy. That was demonstrated in a study of lottery winners who reportedly were much less happy after winning than before.

People whine and complain, pout and overreact, jump to conclusions and take things personally. This not only impacts them negatively but also every person with whom they come into contact, even poisoning the environment.

“So, where do I begin?” asked Angie.

“You begin by choosing to be happy―ongoing. Part of raising your Emotional Intelligence level involves managing your moods. A mood is simply a feeling you choose to hang onto for a long time. You can choose to hang onto happiness. Write down some affirmations and read them aloud several times a day. Reading aloud is more effective than just rehearsal of rote memorization. Remember to use your first name and the pronoun ‘you.’ Try these…

“Angie, you have everything you need. You are happy.”

“Angie, you like being happy. Everything goes better that way.”

“Angie, choosing happiness help you stay upshifted.”

“My brain’s opinion is that Emotional Intelligence should be a required course in the School of Life. High EQ skills are essential for anyone wanting to be happy, healthy, and successful.

“The course requires digging into family-of-origin work and a commitment to honesty. The homework is challenging. The exams, often tough to pass. That’s why many people drop out and fail to keep learning and practicing. In my own life, however, the work has been exponentially worth the effort.”

Grabbing pen and paper, Angie begin writing furiously. At last she sat up straighter and smiled. Not into the camera: into life!

“And Chad?” I asked.

Little humble, Angie responded. “Some of my behaviors have been most unattractive and down-right dysfunctional. As soon as I get home, I shall thank Chad for his patience and apologize for my episodes of pouting. My quiet emotional tantrums, as you put it. I shall also ask him to call my attention to any future behaviors that appear to involve pouting.”

As the song says, “This is how we do it!” Avoiding another fixable fiasco is all about choice!

Hey! Those are Mine!

The pleasure of reconnecting with friends was mine the last time I presented a seminar in Walla Walla, Washington. During the delightful evening I spent with the Trethewey family, our conversation inevitably turned to brain function.

We discussed the seemingly incorrigible human tendency to assume, whenever there is a difference of opinion or thinking style, that the other individual is wrong or at fault somehow. We’re so quick to blame another. Fortunately, applied knowledge, especially as related to current brain-function information, can dampen that predisposition¾ usually to everyone’s benefit!

At one point in our discussion, Ralph related an anecdote he’d read in the book, A Third Serving of Chicken Soup for the Soul. It was a great example of the topic we were discussing. This is what he told me.

It seemed that a traveler had found herself temporarily stranded at a busy airport. To pass the hours before the next flight, she stopped in one of the airport shops and purchased a book and a bag of cookies. The waiting area was jammed with people. Finally locating an empty chair, the weary traveler sank into it and began to read.

Although engrossed in her book, she couldn’t help noticing that the man beside her was helping himself to her cookies. Her first thought was, What nerve! But then she rationalized, Well, it won’t hurt me to share a few. Besides, everyone’s tired here and I don’t want to make a scene.

The minutes ticked by. The woman would help herself to a cookie; so would he. More time passed. Eventually there was only one treat left. I wonder what he’ll do now? She didn’t have long to wonder.

Pulling the last cookie out of the bag, the man broke it in two and, with a nervous smile, offered her half. This was the last straw. She couldn’t remember when she’d been so irritated! Galled, actually. In fact, the more she thought about it, the more incensed she became. Her book lay unread across her lap as the woman mentally concocted a speech. She wasn’t going to let this pass after all. No way. That cookie thief needed to learn some manners!

Before she could give voice to words, however, her flight was called. Gathering up her belongings, the woman passed through the gate and boarded the plane.

Shortly after takeoff, and while still seething inwardly, the weary traveler reached into her bag to retrieve her book. Imagine her shock to have her hand land on a bag of cookies. A bag of unopened cookies. Her bag of unopened cookies.

Alas. Too late she discovered that the cookies she had so readily devoured in the airport had belonged to someone else. The man next to her had actually been sharing his supply with her!

On top of chomping down at least half of his cookies, I almost gave him a piece of my mind, as well, she said to herself ruefully. It was a bit embarrassing to acknowledge that she was the rude one. And she couldn’t even apologize!

Metaphorically, many individuals reenact similar scenes repeatedly—unless and until they learn a new way.

How about you?

Part 01 - IQ+EQ = SQ

Fifty years ago, the terms Emotional Intelligence and Emotional Quotient were not part of mainstream culture. Thanks to Goleman and others, this has changed dramatically.

Even fewer had heard of the Success Quotient, a perceived measure of your overall success in life to date. The formula states: IQ (Intelligence Quotient) plus EQ (Emotional Quotient) equals SQ (Success Quotient).

IQ contributes a mere 20% to success. EQ, a whopping 80%― four times the contribution of IQ.

EQ involves separate skills so does not show up on IQ tests. Yet, EQ matters more than anything else to one’s level of success.

Of your 30,000 genes, about 500 contribute to your IQ, skills related to academic intelligence, of which perhaps 50-80% is inherited from your biological parents. Environment and choice also contribute. A range and not a static number, you may be able to raise your IQ by 5-30 points depending on where you start.

Not an emotion itself, EQ represents a set of skills to help you manage emotions effectively. You can experience them, get their message, choose behaviors that result in positive outcomes, and ultimately increase your likelihood of success.

Although beliefs about emotions differ, uterine scans have shown that facial expressions registering four specific emotions—all positive—are inborn and can be seen on the face of a fetus. Anger, fear, and sadness are protective emotions—although behaviors around them may be negative. Joy is the only emotion with no negative consequences when maintained over time.

Emotions are signals that arise in the subconscious from a stimulus inside or you (thoughts) or outside of you (environment). They connect the subconscious with the conscious mind and provide valuable information. The brain then tries to make sense of the emotion and what you think it means, which results in a feeling. To change the way you feel, you must change the way you think!

What do high EQ skills look like? Check out Part 2.

Part 02 - High EQ!

Most people want to be successful. Many have no idea how to get there. Fewer still understand the role that Emotional Quotient or EQ skills plays in helping a person achieve success.

At birth, if you were fortunate enough to land in an environment where the adults exhibited high EQ, you at least got to observe them—whether or not you chose to build skills for yourself. If, on the other hand, those in your environment had not a clue—you missed that advantage. Nevertheless, since skills that contribute to your EQ are learned—not inherited—you can begin building them any time, and the sky is the limit.

How do EQ skills increase your risk for success? They help you identify what feels good, what feels bad and how to get from bad to good in ways that result in positive outcomes.

Here is a partial list of specific characteristics linked with high EQ.

- Aware and calm

- Peaceful and satisfied

- Balanced sense of self-worth

- Happy, grateful, and appreciative

- Energetic and motivated

- Interdependent rather than excessively dependent or ruthlessly independent

- Contented and consistent

- Able to perceive and expect success

Those are the behaviors I want in myself. Also, in my closest friends and in anyone I might hire.

Although I never met Socrates personally, he reportedly said: the unexamined life is not worth living.

Examine your EQ skills—however uncomfortable it may seem initially. Since you tend to stop maturing emotionally when you experience severe trauma, it’s worth identifying what has happened to you along with your typical behaviors. Explore the history of your biological ancestors—if possible. What you learn may be hard pills to swallow but you can deal effectively only with what you can identify, label, and describe.

High EQ helps you recognize low EQ behaviors quickly—which enables you to course-correct and protect yourself, as needed. The outcome? The liklihood of a higher SQ or Success Quotient.

Low EQ behaviors are uniformly unhelpful. See Part 3.

Part 03 - Low EQ!

No family system is completely functional. Each has its strengths and weaknesses—low Emotional Quotient levels or EQ, for example. Many grew up in environments where undesirable behaviors so commonly occurred, they seemed normal.

While physical maturation is somewhat automatic, mental and emotional maturation are not. Building high EQ skills requires learning and choice. Since you only know what you know, many simply carry learned dysfunctional behaviors into adulthood.

Bad news: growing older is not synonymous with growing one’s EQ.

What do EQ skills look like in adults?

Basically like an unhappy two-year-old throwing a tantrum—trapped in a body that’s somewhere between 18 and 118 years old.

Adulthood tantrums may involve angry outbursts, aggression, rage, tit-for-tat retaliation, gaslighting, and the silent treatment. It can also involve mental, emotional, physical, financial, religious, racial, and sexual abuse. So is consistent criticism of others in an attempt to make oneself momentarily feel better than.

Low EQ is unattractive to observe and horrible to live with! Here is a partial list of characteristics liknked with low—or no—EQ:

- Frustrated, unaware

- Restless, unstable

- Poor self-worth, dejected, lonely

- Unhappy and stressed

- Angry, critical

- Judgmental, blaming

- Too dependent or inappropriately independent

- Expects and perceives failure

Like water, behaviors tend to seek their own level. Low EQ—or high EQ. Whom would you hire? Who are your closest friends? What behaviors do you exhibit?

Just like the range of IQ skills, there is a range of EQ behaviors. Adults can act like babies, unable to delay gratification. Or like some children, pouting, whining, using tears as blackmail, and threatening to “leave.” Or like self-absorbed narcissistic teenagers, defensive, blaming, critical, judgmental, arguing if criticized, refusing to discuss or deal with issues, doing whatever it takes to look better in the eyes of others.

Here is the good news! Since EQ skills are learned, you can start building them any time you want. It is all about choice. Yours.

Meet “J-O-T” in Part 4.

Part 04 - J-O-T & EQ

A jot can be defined as a “tiny amount” or to “write something quickly.” Conflict can begin with a tiny thing. It can occur because one or both individuals process words or events differently and act on that perception quickly.

Three common behaviors contribute heavily to conflict in all relationships. I have labeled them J-O-T—JOT behaviors—and they represent a low Emotional Quotient or EQ.

These are my definitions:

- J stands for Jumping to conclusions

- O stands for Overreacting

- T stands for Taking things personally

When did you last act out a JOT behavior?

Maybe a friend walks by without a hey—or even a smile. In a nanosecond you jump to the conclusion that this “friend” must be mad at you.

You overreact big time, ruminating how badly you are being treated. Then you take it personal.

A week later the friend calls and asks you to lunch. Still angry, you shout, “Are you kidding?” and disconnect. They call again; you don’t pick up. They text; you block their number. Finished.

Unless your friend has a high EQ—it is, finished. You blew up a bridge—all because of JOT. (Genuine love never dies a natural death, you understand. It can be murdered.)

Weeks later you hear that your friend had just received stressful news. Being preoccupied, it’s likely you were never even noticed. Oops. Better repair the bridge.

Unfortunately, this was not the first time you did a JOT behavior—not by a country mile. As such, your friend has moved on. There goes a relationship you might have had for a lifetime. In a professional venue, you may have lost a contract, a plum assignment, a valued colleague, or even a job you needed or wanted.

Everyone has done JOTs—even those with high EQ if they become overstressed. Take note: the higher your EQ, the less likely you are to exhibit JOT behaviors—and leave messes in your wake.

What to do? Try A-A-A. See Part 5

Part 05 - AAA & EQ

Some things are tough on relationships, personal and professional, JOT behaviors, for example: Jumping to conclusions; Overreacting; and Taking things personally. They create conflict!

How can you course correct?

By implementing AAA replacement behaviors. What is AAA? A type of relationship assistance on the road of life.

- A – stands for ASKING questions to clarify the situation instead of jumping to conclusions that may be way off base.

- A – stands for ACTING calmly as you assess the situation and avoiding an emotional tsunami.

- A – stands for ALTERING your perception to avoid taking things personally.

Scrutinize yourself for JOT behaviors. You may initially recognize them only in retrospect. For example, when you find yourself in conflict, perhaps having burned a bridge and ruined a relationship.

Evaluate the consequences of those behaviors. Were the outcomes positive or negative? Before long, with constant vigilance—the blueprint for success—you may become mindful of being in the middle of a JOT behavior and course correct. Immediately!

The long-term goal is to catch yourself before you head into a full-blown JOT and decide if you really want to travel that road again. A better choice: implement AAA. Now!

AAA replacement behaviors can reduce conflict in adults, children, and even in tots.

Your brain can only do what it thinks it can do, and it’s your job to tell it what it can do. Talk to your brain as if it is a separate person—which it is, in a way. Stop telling it what NOT to do and tell it only what you want to have happen.

For example: “JD, you choose AAA replacement behaviors. You ask questions. You act calmly. You alter your perception. You are successful.”

Access willpower to help you build AAA replacement behaviors. Although not designed to stop bad behaviors, willpower can help you learn new ones.

Dump JOT. Sign up for AAA.

Could your EQ use a tune-up? Check out Part 6

Part 06 - Raising EQ

Your behaviors—at least initially—reflect your own family-of-origin issues. These include spoken and unspoken rules handed down, unidentified and/or unhealed woundedness, and layers of cellular memory from biological ancestors—plus all your own life experiences to date.

Low Spiritual Intelligence (or SI)—the spirit with which you live life—or low Emotional Quotient (EQ) does not serve you well in daily living. When both SI and EQ are low, it can be a real challenge to achieving healthy relationships or providing healthy leadership.

No surprise, buildingEQ skills goes faster when you know who you are. Not who someone else thinks you are or who you have been told you are—but who you really are innately. This includes figuring out activities that drain your energy as well as what your brain does easily and well.

Start by reading a story. Pay close attention to the main characters. Do their behaviors result in negative or positive outcomes? Once you can do that in a story, you can do that more easily in yourself.

Or you could begin by building AAA replacement behaviors and course-correcting the moment you recognize a JOT behavior. Find a healthy way to reward yourself every time you STOP before you start down the JOT highway.

Eight behaviors commonly linked with high EQ include an ability to:

- Identify, accurately label, assess level of intensity, and express emotions appropriately

- Recognize what the emotion is trying to communicate

- Articulate the difference between identifying an emotion and taking immediate action

- Identify and decode social cues, understanding the perspective of others regardless of agreement

- Exhibit effective verbal and nonverbal skills

- Manage your own feelings and moods successfully

- Delay gratification and exhibit good impulse control

- Handle relationships effectively

Raising your Emotional Quotient requires a can-do mindset. Studies show that, by maintaining this mindset, your brain can literally rewire itself to facilitate that attitude.

What about EQ in the workplace? That’s in Part 7.

Part 07 - Workplace EQ!

Emotional Quotient (or EQ) is linked with overall success in life. Period. This includes the workplace.

Having employment difficulties? Been fired once or twice? Trouble with relationships? Here’s a consideration: Assess your EQ.

High EQ helps you recognize low EQ behaviors quickly, allowing you to course-correct. The outcome? An increased risk for having a more successful work life on site or when working remotely.

As reported by US News, workplace studies in 2006 estimated that managers spend 18% of their time managing employee conflicts—almost double the 9% identified by similar studies in 1996. Those conflicts typically involved low EQ. Managers spent nearly a fifth of their work hours managing conflict, costing time and energy they could not devote to growing the business.

What employer wants that? Owners and stockholders (if they exist) will not be jumping for joy!

Interestingly, workplace studies also show that successful managers tend to have an average IQ but high EQ. Less successful managers: often a high IQ—but low EQ.

In his book Emotional Intelligence at Work, Dalip Singh, MD, points out that components of high EQ can motivate individuals on the job to maximize productivity, manage change, and resolve conflict.

That enables them to:

- Maintain stable, rewarding, collegial relationships.

- Minimize arguments and resolve disputes, both expensive in terms of physical and mental health and in leadership failure.

- Experience a difference of opinion and still communicate in affirming ways that avoid serious or protracted disagreements that can burn bridges—some irreparable.

- Reduce negative stress, understanding that 70% of contributors to conflict involves one’s own personal history.

- Share an opinion honestly and graciously while remaining relatively indifferent about whether it is accepted. This prevents badgering or bullying in attempt to get others to agree to change their opinion. After all, a brain convinced against its will is of the same opinion still.

A powerful medicine, your Emotional Quotient makes a powerful difference in the workplace.

Bottom line: When you know better, you can choose to do better.

Part 08 - EQ & Self-awareness

Self-awareness involves a personal knowledge of your own character, thoughts, emotions, feelings, desires, and motives, along with a knowledge of how others view you.

Do you know that the essential life skills of Emotional Intelligence (EQ) and self-awareness are linked hand in glove? They are linked because building EQ skills requires strong self-awareness. Although many believe they have high self-awareness, studies estimate that only one in 10-15 individuals really possesses those skills for accuracy. You cannot take steps to get out of a trap if you do not even realize you are in one.

Considering almost any hierarchy, people considered the “higher ups” are least likely to be self-aware of how others perceive them. Why? Because there are fewer individuals “above” to provide kind and helpful feedback. And those “below” may be unwilling to take the risk.

—Pay attention in the moment to what is happening both inside of you and in your environment. Imagine watching yourself from the outside, monitoring your appearance and behaviors, and noting how they affect your interactions and relationships.

—Learn to identify your emotions quickly and accurately, what likely triggered them, and what they are trying to tell you. Do they relate to your past? If so, take steps to heal and release emotional baggage.

—Be open to feedback. View their comments dispassionately. It is, after all, only their opinion. Plus, you can become more self-aware of your behaviors and how they are perceived, at least by some. There’s always something you can learn.

—Avoid “why” questions (e.g., why did I say or do that?) which lead to rationalization. Instead, ask “what” questions, e.g., what steps must I take to avoid these less-than-desirable behaviors in the future?

—Hang out with self-aware individuals; they can help you sharpen your skills. Treat others as you would prefer to be treated. What you circulate into the environment often comes back to you.

Building Self-awareness skills can help you build Emotional Intelligence skills—worth 80 percent of your overall success in life. These two essential life skills are linked, hand in glove.

Part 09 - EQ & Conflict

Conflict—that is, discord between two or more entities—is expensive. Conflicts can range from minor differences of opinion to contentious, cataclysmic disputes that include mob action or wars. It can include generational conflict as families pass down vendettas from one generation to the next.

In the home, conflict contributes to stress, unhappiness, illness, addictions, divorce, violence, and even murder. In schools and churches, conflict burns out personnel, triggers arguments and misunderstandings, and can also escalate into violence and bloodshed. In the workplace, conflict increases stress, drains personnel, contributes to higher rates of absenteeism and workers comp claims that trims profits from the bottom line. As of 2021, estimates are that managers spend at least 25 percent of their time resolving workplace conflicts—one of the biggest challenges companies, managers, and employees face.

Estimates are that 70 percent of contributors to conflict involves your own past experiences and the resulting impact on your response in the present moment. Conflict typically reflects low levels of Emotional Intelligence (EQ). High EQ skills help you realize that you are under no obligation to accept an invitation to an argument. That, in itself, can help to minimize—if not avoid—situations of conflict. EQ skills help you decide when to walk away from a situation because the likelihood of resolving the conflict is slim to none.

High EQ allows you to share your brain’s opinion as honestly and graciously as possible and then remain healthfully indifferent to whether your opinion or recommendation is taken. After all, the opinions of others are none of your business. This helps you evade badgering others to embrace your perspective and burning bridges that may not be reparable.

Of all the problems people experience, about 50 percent are of their own making, based on their thoughts and choices. Imagine dumping at least half of all your problems off the back of your lifetime-pickup truck!

Overall, EQ skills can help you avoid making serious and sometimes permanent life-impactful decisions based on temporary emotions and feelings.

To live out your days in conflict is expensive. Countering discord with high EQ skills is worth its weight in gold.

Part 10 - EQ & Leadership

The concept of leadership is complex. After all, there are billions of brains on Planet Earth and probably as many ways to “lead” as brains thinking about it.

In adulthood, you provide leadership for yourself: your decisions, behaviors, and choices when relating with others. If you are a parent, you provide leadership for younger family members; if a teacher, for your students. In business, you can provide leadership for a department, project, or the entire organization.

Leadership styles reflect one’s level of EQ skills and ability to role-model them. Leadership success involves the interplay between one’s Intelligence Quotient (IQ) and one’s level of Emotional Intelligence (EQ).

Although not a fixed number, IQ represents a range of largely inherited potential academic intelligence. EQ is a set of learned skills that are distinct from, but complementary to, academic intelligence. This IQ-EQ interplay is affected by many factors: one’s generational biological inheritance, past experiences, the impact of closest friends (especially those with whom one spends the most time), willingness to learn, and a personal choice to build EQ skills.

Based on the Success Quotient (SQ) formula—IQ plus EQ equals SQ—estimates are that IQ contributes only about 20 percent to one’s overall success in life, while EQ skills contribute about 80 percent. Studies in the workplace have shown that successful leaders tend to exhibit high levels of EQ skills—although their IQ levels are often average. Less successful leaders often have a high IQ but low levels of EQ skills.

According to Dr. Daniel Goleman, “CEOs are hired for their intellect and business expertise and fired for a lack of emotional intelligence.”

Without high EQ skills, leadership reflects the individual’s own family-of-origin issues, the spoken and unspoken rules handed down, unidentified and/or unhealed woundedness, and past personal experiences—all packaged in layers of cellular memory from 3 to 4 previous generations of biological ancestors.

Healthy, functional, and successful leadership requires solid EQ skills. Top leadership performers tend to use both IQ and EQ skills. Refer to Part 2 of this series for examples of high EQ behaviors. How many do you need to build? The sky is the limit.

Part 11 - EQ & Delayed Gratification

Delayed gratification is a label that describes an ability to resist an immediate reward, hoping to obtain a more valuable reward in the future. Essential for self-regulation, self-control, goal achievement, and success, it is a learned skill.

In the 1960s, psychologist Walter Mischel began a longitudinal study on deferred gratification designed to measure the willpower of 4-year-old children to delay gratification. Eventually, known as the Stanford Marshmallow Experiment, Mischel placed a large marshmallow in front of 653 children. Each child could choose to eat it immediately or, if after waiting for 15 minutes until the researcher returned to the room, have two marshmallows.

Two-thirds of the 4-year-olds ate their marshmallows before the researcher returned. A few children even tried to “bully” others into giving up their marshmallows, reinforcing an emerging understanding that bullying behaviors are learned.

One third of the children waited and received a second marshmallow. These particular 4-year-olds seemed to think differently. They sang songs, tapped feet, told stories, played games, walked around the room, closed their eyes, or even fell asleep while waiting.

A 1988 follow-up found that those who had gotten a second marshmallow were more socially competent and self-assertive. They also exhibited more resilience in dealing with life’s frustrations. A 1990 follow-up showed that the 2-marshmallow youth had applied deferred gratification in pursuit of their goals. They averaged 200 points higher on their SAT college-entrance exams and were already more successful than the eat-it-now children.

In 2011, a sample of the original participant group received brain imaging. Scans showed two key differences in two brain areas in participants who had received 2 marshmallows. Their prefrontal cortex (involved in planning, evaluating, deciding, choosing, and willpower) was more active. The Ventral Striatum located deep inside the brain and affecting mood, addiction, and learning, was also more active when the 2-marshmallow participants were endeavoring to delay gratification.

Even if you might have been in Mischel’s two-thirds group of eat-it-now children, in adulthood you can intentionally learn to delay immediate gratification. Linked with high EQ Skills, an ability to delay gratification is essential for self-regulation, self-control, goal achievement, and success.

Part 12 - EQ & Communication

Emotional Intelligence skills can help you clearly communicate your thoughts and influence others with your words. The conscious brain uses language and turns what you say, read, and hear into brain pictures. This allows the huge subconscious mind—that does not use language per se and that is more powerful than the conscious mind—to follow the pictures language created. Thus is critically important to use the most effective words when communicating what you want to happen.

When telling your brain what to do, avoid the word “I” as it tends to trigger the ego in the mammalian (2nd brain) layer. Avoid future-tense words like “I’m going to….” The brain understands future tense and may think: That is then and this is now. When now comes, I’ll help you—if you still want to do it.

Brain imaging studies have discovered a more effective self-talk style that creates more accurate brain pictures. Use your given name so the brain knows who is talking, the pronoun you, and present tense words to tell your brain what to do. Say, “Farquart, you are walking for 15 minutes.”

Use positive words and phrases. Negatives are a two-step process. The word “don’t” implies that you should do the opposite of what you just said (or heard). However, the brain may either miss the don’t or fail to convert the first picture it created. The phrases “Don’t touch the stove,” (negative) and “Keep your hand away from the stove,” (positive) create entirely different pictures in the brain.

Stop talking about what you do not want to happen. The goal is to trigger the brain to create a picture of what you want to happen for the subconscious to follow. Say: “Sally, speak quietly,” rather than “Don’t yell.” “Sam, remember your homework,” not “Don’t forget your homework.” “Ingrid, share with your sister,” instead of “Don’t be so selfish.” “Tom, you are learning,” rather than “Don’t be such a dunce!”

Speak so the brain creates a picture of what you do want to happen—in your brain and in the brains of others. It’s a win-win!

Part 13 - EQ & Relationships

he human brain is a relational organ. How you approach relationships is as unique as your own brain. Your most important relationship is the one you have with yourself. You are the only person who will be with you for your entire life. The way you treat others tends to mirror how you treat yourself.

Daniel J. Goleman, PhD, has pointed out that one aspect of successful relationships is not just how compatible you are with each other, but how you deal with incompatibility—present by degrees in every relationship. When EQ skills are slim to none, family relational patterns from the past play out in present relationships without the individuals necessarily even being aware.

High EQ helps you identify what feels good, what feels bad, and how to get from bad to good in a way that results in positive outcomes. Because the brain likes to feel “good,” it may push you—based on past experience— toward behaviors it thinks can help you feel “good” or at least feel “better.” There is a healthy feeling good with positive outcomes and a pseudo feeling good with negative outcomes, typically involving addictive or dysfunctional behaviors.

Paying attention allows you to build emotional connections with others. Simple inattention kills connection, empathy, and compassion. Stop checking your cell phone repeatedly. Turn off electronics periodically. Exchange quality attention in the moment. This can help you achieve safe, resilient, healthy, and rewarding relationships.

Building EQ skills helps you differentiate between caring and manipulation, between offering help when it is genuinely needed and simply giving in to another’s every wish or demand or imposing your own preferences. After all, knowing what someone else thinks and wants does not mean always agreeing with them. Every brain on Planet Earth is unique with its own opinions, which may differ from yours.

EQ skills help you make ethical and moral decisions about how to take care of yourself and how to respond to others appropriately. High EQ assists you in developing healthy and reciprocal relationships. You take care of your own needs and some wants, while sharing and receiving in balance from others!

Part 14 - Benefits of High EQ

In his book Emotional Intelligence at Work (2006), Dahlip Singh, PhD, pointed out that building EQ skills in life can help you in many ways. You can maximize your own productivity; avoid, minimize, and/or resolve conflict; handle change effectively; and exhibit empowering behaviors. You can also manage your emotions and feelings to help self-regulate brain chemicals and hormones—increasing both intuition and clarity.

EQ skills help create emotional competence as you:

- Tackle emotional upsets, avoiding emotional exhaustion or “stuffing it.”

- Develop optimum levels of self-esteem—neither over- nor under-inflated.

- Select tactful responses to emotional stimuli, knowing that sometimes no immediate response is most appropriate: you simply observe and learn.

- Handle egoism by taking initiative to increase your self-awareness.

EQ skills help develop desirable behavioral characteristics such as:

- A healthy superego that promotes moral integrity and appropriate social standards.

- Awareness of how others perceive you, neither over-estimating nor under-estimating your knowledge and competence.

- An ability to delay immediate gratification for a larger and more desirable long-term goal.

- Adaptability, understanding that the only constant in life is change.

- Flexibility, knowing that “more than one road leads to Rome.”

EQ skills aid in developing emotional maturity, helping you:

- Recognize and respond to emotional stimuli of low intensity without needing a “hit over the head” before you recognize the emotion.

- Show appropriate empathy, e.g., not merely acknowledging that someone is struggling.

- Manage interpersonal relationships effectively, including the ability to avoid or walk away from abusive situations or environments, asking for help as needed.

- Tend to “live at joy” most of the time, being thankful and grateful.

- Avoid becoming incapacitated by the choices of others.

- Communicate positive emotions through mindset, self-talk, and affirmations.

Hone your EQ skills by using them consistently in all your interpersonal interactions, allowing others—especially those who are younger—the opportunity to observe your EQ role-modeling in real time. You may be the only person they know who is showing high levels of EQ. These skills can help you leave your corner of Planet Earth a better place than you found it. What an opportunity! What a legacy!

When the Answer Is Always “No”

Thursday. The end of a hectic school day. A HOT hectic school day. The air conditioning had decided to take a break on one of the hottest days so far that September: picture-taking day for the school yearbook. I fear the pictures will reflect a lot of sweaty faces and some rather damp and stringy hair, the school nurse mused, anticipating her own air-conditioned home. And not a minute too soon! Closing her desk, she prepared to retreat.

A knock on the door. “It’s open!” Two girls—barely teenagers— pushed their way into the health office.

“What can I do for you girls?” the school nurse asked, smiling tiredly.

“My mom is sitting the car crying,” said Nancy. “She won’t tell me what is wrong. But she is really, really upset.”

“It is very fortuitous,” said Aimi, her arm around Nancy’s shoulders. “Fortuitous that you are still here—not that Nancy’s mother is upset, of course. But maybe …” She looked at the school nurse with a please-can-you-do-something-to-help-her expression. “Maybe you could talk to her mom?”

“Nancy, please ask your mother if she’d like to come into the school and chat for a few minutes,” the nurse said. “Perhaps you girls could spend a little time on the swings—or, if it is too hot, play piano duets in the music room.”

The two girls were out the door in an instant.

Nancy’s mother did want to chat. But once in the health office, Megan just sat and cried. And cried. Finally, the school nurse said, “If you want to share with me what happened, perhaps I can help.”

Gradually the sobbing morphed into hiccups; the hiccups dissolved into several large sighs. “It was my birthday last Monday, and all I got from my husband was a card. And I did not get that until Tuesday morning at breakfast! I feel so devalued. I cannot seem to think about anything else. It is gotten worse every day this week. In the car I finally had a total meltdown.”

“Did you want something besides a card?” the nurse asked.

“Of course, I wanted something else!” the woman snapped, her sighs turning into outright indignation. “What do you think?”

“I cannot assume what you wanted,” the school nurse said, kindly. “You will need to tell me.”

A little more prodding revealed that Megan had wanted to go to on a dinner date to a new restaurant.

“Is going out for a dinner date to a new restaurant well within your budget?” the nurse asked.

It was.

“Did you tell your husband that a birthday dinner date was what you wanted?”

Megan mumbled something indistinctly.

“I didn’t get what you said,” the school nurse responded.

Silence.

“I cannot help you unless you are willing to communicate,” said the nurse.

Several very large sighs ensued. In the end it turned out that Megan had not reminded her husband of the upcoming birthday nor had she said anything about what she wanted. When the school nurse questioned the reason for this complete lack of communication, Megan again mumbled something indistinctly.

Silence. The school nurse waited.

Eventually, Megan spoke her mind. “If he loved me, my husband should be able to remember my birthday and figure out what I would like for a present!”

That led to a rather lively discussion.

“No matter what you may have come to believe,” the school nurse explained, “the human brain is unable to read another’s mind.”

Megan glanced at her sideways.

“No matter how much your husband loves you, he may have had no clue about what you wanted for your birthday—obviously, he didn’t have the date written in his calendar, either.”

“He could have asked…” Megan replied, her mouth in a pout.

“You could have reminded him,” the nurse countered.

“Whose side are you on?”

“I am on the side of acting like a responsible adult and communicating effectively. Not on the side of unrealistic expectations, over-reacting, and taking things personally. That represents J-O-T behaviors and low levels of Emotional Intelligence.”

“I never heard of J-O-T. How does that play into my sorry story?”

“J stands for jumping to conclusions. You jumped to the conclusion that your husband could read your mind and just chose not to do so. O stands for overreacting. I would say nearly three days of sobbing is in that category. And T stands for taking things personally. Your saying ‘If my husband loved me,’ represents taking it personally.”

“But if I have to ask, then dinner wouldn’t mean anything!” Megan was no longer mumbling.

To her credit, the school nurse really tried to keep a straight face. She really did. She failed, however. Busting into laughter, the nurse said, “Oh, for crying out loud. That is about as dysfunctional a perspective as I have heard in many a year. Nothing like expecting too much of your husband and then getting bent out of shape if you give him a clue and he jumps on it. Honestly!” And she burst into gales of laughter. It had been a long HOT day!

Megan tried hard to retain her pout, tried not to grin back. But a slight lip-twitch gave her away.

It was at that juncture that first Aimi, then Nancy stuck a head around the crack in the doorway. Seeing her mother no longer sobbing uncontrollably, Nancy’s face showed a rather comical relief. No matter the age of a child, no one likes to see their mother crying in pain.

“Come on in, girls,” said Megan. “You may as well learn this sooner than later.” In a few sentences she explained how upset she had been about just getting a card for her birthday—and that a day late! To her credit, she also said that she had not reminded her husband of her upcoming birthday nor had she told him of her wish for a dinner date at the new restaurant.

The nurse was direct. “You need to tell your husband what you want. You may not get it in every instance, but articulating it gives you a better chance. And he will not have to guess. If you do not ask, the answer is always no.”

“You always ask me what I want for my birthday,” said Nancy, taking her mom’s hand.

“And my parents always ask me what I’d like for mine,” chimed in Aimi.

“I guess I do like to give Nancy what she asks for, whenever I can,” said Megan.

“I rest my case,” the nurse said, simply.

“I have an idea!” cried Aimi. “Tell your husband you’re sorry you didn’t remind him about your birthday. Negotiate to have a delayed birthday date night next week at the new restaurant.”

“Brilliant idea!” said Nancy, jumping up and down.

“And maybe Nancy and I can have a sleep-over that night,” said Aimi, hopefully. “If you can have the delayed birthday dinner on Friday or Saturday evening. School, you know.”

“I’m on it,” said Megan, turning toward the nurse. “And would you have some time to help me learn more about EQ and JOT? Somehow I must have missed those skills growing up.”

The nurse could—and would. Megan and Nancy left the office, Nancy waving good-bye.

“I told you it was fortuitous!” said Aimi, laughing. “Thank you for helping Nancy’s mom!” And Aimi was out the door, too.

Telling those you care about what you would like on a special occasion seems like such a simple thing to do, mused the school nurse. After all, it is not brain surgery … it is brain science, however. No one can “read” another’s mind….

She locked the door to the health office, anxious to get home. Chatting had helped Megan cool down; the nurse reflected. “And now it’s my turn to cool down!” she said out loud—only to herself. “Air Con here I come!”

The Emotions Staircase portrays core emotions as a series of steps. Metaphorically, you will be standing on one of the steps at any given moment. With increased awareness of your own emotions and by implementing strategies for managing them more effectively, you can learn to spend most of your time on the step of Joy and typically move to another step only when the present situation warrants it. While not thought to be an emotion in and of itself, Apathy may represent a state of being emotional overwhelmed in which the individual becomes immobile. Human beings rarely try to commit suicide when in a state of apathy. They don’t have the energy! They can be at higher risk for suicide attempts as they begin to move back up the Emotions Staircase and get more energy.

The Emotions Staircase portrays core emotions as a series of steps. Metaphorically, you will be standing on one of the steps at any given moment. With increased awareness of your own emotions and by implementing strategies for managing them more effectively, you can learn to spend most of your time on the step of Joy and typically move to another step only when the present situation warrants it. While not thought to be an emotion in and of itself, Apathy may represent a state of being emotional overwhelmed in which the individual becomes immobile. Human beings rarely try to commit suicide when in a state of apathy. They don’t have the energy! They can be at higher risk for suicide attempts as they begin to move back up the Emotions Staircase and get more energy.