The concept of downshifting appears to fit with both what is now known about the triune nature of the human brain and what is observed in instructional settings and activities of daily living.

—Leslie A. Hart

Human Brain and Human Learning

“My brain is like a what?” His handsome face was wreathed in puzzlement.

“Like an automatic transmission,” I replied. “Metaphorically, the human brain can be described in terms of three functional layers or gears, much like those of an automatic transmission.”

“And the purpose of these gears?” he asked.

“So you can drive smoothly on the highway of life, slowing down and speeding up, shifting down and shifting up as necessary—based on highway conditions—in order to arrive safely and timely at your destination. Generally, you want to drive in the third or top gear as much as possible, accessing second or first gear only when those gears are needed.”

“Just to be sure we’re on the same page,” I continued, “imagine you’re heading to Lake Tahoe for a weekend of skiing, driving a vehicle with an automatic transmission. (Everyone in California knows about Lake Tahoe!) You pass the 3,000 foot elevation marker, then the one for 5,000 feet. As you continue toward the 7,000 foot marker the highway narrows and becomes steeper. Snow begins to fall, and traffic backs up. What do you expect your vehicle to do automatically?”

“Shift down, of course,” the man answered. “My part is to stay off the horn. I think I’ve finally learned that snow is oblivious to the sound of honking. Pretty much so is traffic.” We laughed. How true.

“How far down will it shift?” I asked.

He stroked his carefully trimmed beard, thoughtfully. “Only as far as necessary to help me get through.”

“Great answer,” I said. “Sometimes when I ask that question I hear ‘to first gear, of course.’ Not necessarily. Your vehicle will go to first only if it cannot get through in second.”

He nodded in agreement.

I continued. “What happens if it shifts down to first and is still unable to get through?”

“The engine will stall,” he replied, “and most likely I’ll have to stop and put on chains. Nothing I’m excited about experiencing on my way to Tahoe for a skiing weekend!”

“Now imagine the reverse. Not the gear, the situation,” I clarified. “The road flattens out, it stops snowing, and traffic disperses. Now what do you want your vehicle to do?”

“Upshift.”

“What are the consequences if it fails to upshift?”

He listed several possibilities in rapid-fire succession:

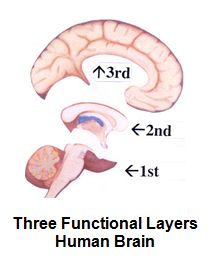

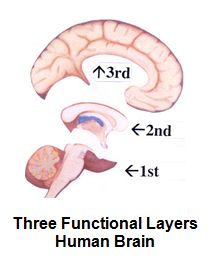

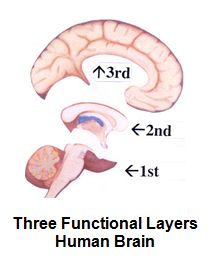

To make it more real, I suggested that he imagine his left wrist as first gear, his left fist as second gear, and his right hand placed over the top of his left fist as third gear. “If you could move that into your skull, it would resemble the three brain layers,” I told him. (Refer to drawing of the three layers on the right.)

“Interesting,” he said. “What life-highway conditions would require use of second or first gear?”

“Interesting,” he said. “What life-highway conditions would require use of second or first gear?”

“The brain tends to downshift in situations that involve trauma, crisis, fear, anxiety, negative experiences, or mindsets that promote a sense of helplessness,” I said. Then I gave him a list:

“Like being bullied,” he said. “I’m currently working with a teenager whose brain is likely downshifted from experiencing bullying behaviors. This helps explain a lot.”

Self-destructive behaviors, sometimes as a response to unmanaged stress or trauma, can kick the brain out of third gear, as well. These may include eating disorders, drug abuse, unbalanced living, addictive behaviors, compulsive sex or shopping or gambling, and the excessive use of electronics (including violent video games).

When confronted with these types of situations, the brain tends to downshift, searching for functions to enhance its sense of safety.

Some activities serve to highjack the third brain layer. They may or may not trigger downshifting, but they can interfere with high-level executive brain functions. I think of them as “brain suspenders” (e.g., specific types of music, flashing disco lights, extreme hunger, use of alcohol and various drugs), which temporarily suspend clear thinking, rational judgment, and effective decision-making.

Some activities serve to highjack the third brain layer. They may or may not trigger downshifting, but they can interfere with high-level executive brain functions. I think of them as “brain suspenders” (e.g., specific types of music, flashing disco lights, extreme hunger, use of alcohol and various drugs), which temporarily suspend clear thinking, rational judgment, and effective decision-making.

“Do I take it to understand that any type of fear can trigger downshifting?” he asked

I responded to that good question. “According to Joseph Chilton Pearce in The Biology of Transcendence, fear of any kind can throw the brain into a survival mode that when fully active, shuts down higher levels of awareness. This results in a shift of attention and energy away from the cerebrum and toward the brain stem. In such instances, humans tend to react on a more primitive level.”

The fear can be real (an actual danger) or imaginary (e.g., a fear of failure, of not being loved, of being unable to care for one’s self). The emotion of fear is essential to living safely, because it alerts you to situations that could pose a danger. Unfortunately, much of the fear people tend to harbor in their minds and bodies has nothing to do with actual danger. Rather it is imaginary fear that may have its basis in past experiences, self-esteem issues, learned patterns of negative thinking, unhealed wounds, lack of specific skills related to living successfully, and sometimes a failure to leave childhood defense mechanisms behind and grow up into a mature adulthood.

If you recognize fearful thoughts, ask yourself some questions and then pay attention to your thoughts:

“Very helpful,” the man said, again stroking his carefully trimmed beard. It was a very classy beard. “I can use this information when I lead group therapy sessions. And it shines a new light on the Serenity Prayer. Thanks.”

He was more than welcome.

*Grant me the serenityto accept the things I cannot change;

courage to change the things I can;

and wisdom to know the difference.

—Reinhold Niebuhr (1892–1971)

©Arlene R. Taylor PhD arlenetaylor.org

Ignoring who you truly, authentically are can literally be killing you… Forcing yourself to be someone you are not or stuffing down who you really are…will tax you so much that it will shorten your life by years and years.

—Phillip C. McGraw PhD, from his book Self Matters

In the mid ‘70s after experiencing firsthand the exhaustion of burnout and mid-life crisis, Taylor became even more interested in the concept of energy. With increased awareness, she noticed others whose symptoms appeared to match hers. Taylor interviewed some of these individuals, several of whom had sought care due to suspected PTSD (Posttraumatic Stress Disorder). According to their respective physicians, however, the patients’ reported symptoms did not meet the classic definition for PTSD. While some symptoms mirrored PTSD, there were two notable exceptions:

Over time, Taylor continued to interview individuals and identified a collection of symptoms that seemed to be exhibited fairly consistently, although the actual level of symptomatology varied based on the person’s own history. A common theme ran through their histories: they expressed disappointment and dissatisfaction with life as they had been living it for the past decade or so. The reasons for this dissatisfaction were, at times, nebulous, but life clearly wasn’t working for them, at least not in ways they had been led to believe life should or could work. Persistent fatigue was a key trigger for seeking consultation, a fatigue that couldn’t be tied to anything specific. None had been diagnosed with an illness, disease, or condition that would be associated typically with energy drain (e.g., Infectious Mononucleosis, CFIDS or Chronic Fatigue Immune Dysfunction Syndrome).

In their search for answers, many of these individuals reported having completed assessments such as Herrmann’s Brain Dominance Inventory, the Myers Briggs Temperament Inventory, Benziger Thinking Styles Assessment, Blitchington’s and Cruise’s Four Temperament Inventory, the Keirsey-Bates assessment or the Johnson-O’Conner aptitude testing. They were able to articulate examples of tasks during the performance of which they felt good and had plenty of energy. But when the opposite occurred, they felt drained and disappointed, uncomfortable and even exhausted. In general, the more time they had spent completing these types of energy-exhausting tasks, the more PASS symptoms they reported. This further reinforced Taylor’s perception that the reported energy drains were related to the types of tasks these individuals were asking their brains to complete.

For purposes of sharing her observations in a more formal manner, Taylor arrived at the acronym PASS, Prolonged Adaptive Stress Syndrome, to describe the eight commonly observed symptoms that may be present in varying degrees in individuals who have spent years living an energy-exhausting lifestyle.

1. Fatigue

The brain likely has to work much harder when trying to accomplish tasks that do not match its own energy advantage. The additional energy-expenditures can contribute to an increased need for sleep, interference with sleep, decreased dreaming, and a progressive fatigue that is not alleviated by sleep.

2. Hypervigilance

Living an energy-exhausting lifestyle can push the brain to activate a protective safety mechanism. The Reticular Activating System or RAS can push the individual into a state of protective alertness. This sense of hypervigilance can be exhibited as a startle reflex, an increased sense of generalized alarm, or as restless jitteriness.

3. Immune System Suppression

Stress can suppress immune system function (e.g., temporarily shrink the Thymus gland). Outcomes related to immune system suppression can include a slowed rate of healing, exacerbation of autoimmune diseases, an increased susceptibility to contagious illnesses, and/or an increased risk of developing diseases such as diabetes and cancer.

4. Reduced Function of the Frontal Lobes

Some individuals experience a decrease in artistic or creative competencies (e.g., writer’s block, difficulty brainstorming options, diminished problem-solving skills). Others evidence interference with their ability to make logical or rational decisions, exhibit a tendency toward increased injuries due to cognitive impairment, or notice slowed speed of thinking and/or reduced mental clarity.

5. Altered Neurochemistry

Interference with hypothalamus and pituitary function can affect hormonal balance (e.g., decreased growth hormone, insulin production irregularities, alteration in reproduction functions, and an increase in glucocorticoids that can prematurely age the Hippocampus). Reports from mice/rat studies suggest that altered neurochemistry due to extreme or prolonged stress may interfere with the permeability of the Blood Brain Barrier.

6. Memory Problems

Cortisol, released under stress, can interfere with memory functions. Dr. Robert Sapolsky of Stanford University and author of Why Zebras Don’t Get Ulcers outlined several consequences:

7. Discouragement or Depression

Conserve/Withdraw is a reaction form that the brain may use when an event or situation seems overwhelming and for which there seems no ready solution. Experienced over time, this can lead to discouragement and a sense of hopelessness, even exacerbating existing depression. Estimates are that 20 million people in the United States may be depressed at any given time, with approximately 15% of those being suicidal. No surprise, exhaustion can contribute to both discouragement and depression.

8. Self-Esteem Problems

A perceived lack of success in life, as well as the cumulative impact of PASS symptoms, can whack one’s sense of self-worth and/or exacerbate existing self-esteem problems. Behaviors may appear that mirror low self-esteem (victim mindset) and/or inflated self-esteem (offender mindset). An altered sense of self-worth can also impact the way in which an individual exhibits personal self-care.

Based on PET (Positron Emission Tomography) Scans, Dr. Richard Haier of San Diego has estimated that the brain may need to work 100 times harder second per second when an individual develops and uses skills outside of his/her area of energy advantage.

As Taylor and others have noticed, when the brain is forced to spend large amounts of time completing tasks that are energy-exhausting, the individual may experience chronic anxiety and eventually exhibit symptoms of PASS. The number and/or severity of PASS symptoms likely has to do with the length of time the person lived an energy-exhausting lifestyle.

Stress Equation

The brain is the first body system to recognize a stressor and it reacts with split-second timing. It can stimulate the stress response for up to 72 hours after a traumatic event—real or imagined—longer, if you keep rehearsing the event in detail.

It has been said that stressors generally interact with the brain in a predictable 20:80 ratio. Sometimes referred to as the 20:80 Rule, it states that:

It is possible that the adverse affects on the brain and body resulting from life situations that lead to PASS symptoms may exceed the typical 20%. This seems likely, given that this form of stress involves not only external and environmental triggers but also the rate at which the brain itself must work and the amount of energy that must be expended in order to accomplish the desired tasks.

By virtue of the increased energy expenditure, this type of adapting may be considered a major life stressor. Over time, it may also contribute to an increased risk of self-medicating through addictive behaviors in an attempt to alter one’s own brain chemistry and “feel better.” At least it is an area worth evaluating, especially if the individual recognizes several of the PASS symptoms.

By Arlene R. Taylor PhD, and I. Katherine Benziger, PhD

OVERVIEW

Human beings are perhaps healthiest, happiest, and most successful when they can use and be rewarded for using their own innate giftedness, or what Jung and Benziger call their natural lead function. Indeed, it can be said that when a person develops and uses his/her natural lead function in an environment which both supports and rewards that function, the experience is similar to if not identical with the experience of flow, identified by Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi in Flow: The Psychology of Optimal Experience.

For whatever reason, when this does not occur the brain is forced to spend large amounts of time functioning from areas requiring significantly greater expenditures of energy. In other words, the brain is forced to Falsify Type. The result is that the brain and brain-body system experience stress, chronic anxiety and exhaustion. Indeed, Falsifying Type is so costly that over time it can lead to the development of a syndrome identified by Taylor as PASS or Prolonged Adaptive Stress Syndrome. Significantly, one element of PASS is the experience, seemingly without cause, of chronic depression.

BACKGROUND

Dr. Carl Gustav Jung originally coined the term Falsification of Type to describe an individual whose most developed and/or used skills were outside one’s area of greatest natural preference. In his writing, Jung stated that he believed the problem to be a serious one with both practical and psychological ramifications. Indeed, Jung saw Falsification of Type as “a violation of their natural disposition,”[1] explaining that:

As a rule whenever such Falsification of Type takes place as a result of external influence, the individual becomes neurotic later, and a cure can successfully be sought only in the development of the attitude (e.g., function) which corresponds with the individual’s natural way.

In the last analysis, it may well be that physiological causes (inaccessible to our knowledge in 1926) play a part in this. That this may be the case seems not improbable, in view of one’s experience that the reversal of type often proves exceedingly harmful to the physiological well-being of the organism, often leading to an acute state of exhaustion.”[2]

Dr. Benziger, who established and studied the physiological foundations for Type and Falsification of Type over the past two decades, expanded on Jung’s observations regarding the results or costs of Falsifying Type. Benziger, using her Benziger Thinking Styles Assessment (BTSA) to gather and study data of individuals who had been or were Falsifying Type. In her summary report on the topic, Falsification of Type: Its Jungian and Physiological Foundations and Mental, Emotional and Physiological Costs, published in 1995, she stated that:

Benziger’s observations and thinking are supported by the research of Dr. Richard Haier of San Diego. Using PET scan studies, Haier demonstrated that the brain needs to work much harder when not using the person’s natural lead function (which he establishes as an area of exceptional natural efficiency).

Haier estimated that the brain may need to work as much as 100 times harder when an individual is developing and / or using skills outside one’s area of natural efficiency.

Such a demand on the brain requires huge amounts of energy and oxygen. This not only pushes the brain to “burn hotter”, as it were, but could also over time throw off the person’s innate homeostatic balance in the area of oxygen usage and distribution. Normally the brain uses approximately 20% of the oxygen taken in through the lungs. This leaves about 80% for the rest of the body where it is utilized in the process of metabolism and in providing energy at the cellular level and overall. As more and more oxygen is demanded by the brain that is falsifying type, less and less is available to keep the rest of the body up to speed. A variety of symptoms can result (e.g., fatigue, digestive problems, listlessness). Indeed, over time, the oxygen imbalance can contribute to the person’s body shifting from anabolic to catabolic functioning.

Taylor, over an eleven-year period during which she worked with clients reporting symptoms of depression and apparent PTSD, observed that specific symptoms seemed to be present in individuals who were Falsifying Type—living in a state of prolonged adapting as evidenced through the BTSA profile. In addition, her observations led her to theorize that in some cases, individuals who were being diagnosed with PTSD or depression, might not be suffering from PTSD or depression per se (not as the underlying contributing factor), but rather from Falsifying Type. Taylor’s findings suggest that Falsifying Type may be best understood as a separate, discrete, and treatable syndrome, although it can contribute to the exacerbation of a variety of other illnesses. For some individuals, it can also be life threatening. Subsequently, to facilitate sharing her findings with others, Taylor assigned the label PASS (Prolonged Adaptive Stress Syndrome) to identify the predictable collection of symptoms which seem to appear when an individual has been Falsifying Type.

PASS

Eight commonly observed symptoms may be present in varying degrees in individuals who have been Falsifying Type. This collection of symptoms can include:

1. FATIGUE. Prolonged adapting can require the brain to work up to 100 times harder, which can result in up to 100 times greater energy expenditure. This can be observed as:

2. HYPER-VIGILANCE. Prolonged adapting can create a state of hyper-vigilance as the brain goes on protective alertness. This is a safety mechanism and can show up in a variety of different ways:

3. IMMUNE SYSTEM ALTERATION. Falsifying Type can be thought of as the individual living a lie at some level. Lying can suppress immune system function (e.g., can temporarily shrink the Thymus gland) which can negatively impact one’s health. Symptoms that can be seen include:

4. MEMORY IMPAIRMENT. Cortisol, released under stress, can interfere with memory functions. Examples from Robert Sapolsky’s book, Why Zebras Don’t Get Ulcers, include:

5. ALTERED BRAIN CHEMISTRY. Prolonged adapting can interfere with hypothalamus and pituitary function which, in turn, can interfere with hormonal balance. This may be observed as:

6. DIMINISHED FRONTAL LOBE FUNCTIONS. Prolonged adapting (viewed as a significant stressor) can interfere with functions typically associated with the frontal lobes of the cerebrum. Symptoms can include:

7. DISCOURAGEMENT AND/OR DEPRESSION. Prolonged adapting can lead to the repeated triggering of the conserve/withdraw reaction form to stress. This can be especially true for high introverts although it can be observed in extraverts who, as years go by, continue to perceive a mismatch between who they are as individuals and societal expectations and/or repeated episodes of failure. This can lead to discouragement, especially as fatigue increases, and can contribute to the development of depression or to the exacerbation of existing depression. Estimates suggest that upwards of 20 million individuals in the USA are depressed, 15% of whom are suicidal. Prolonged adapting appears to be a key factor in at least some of these cases.

8. SELF-ESTEEM PROBLEMS. Any or all of the other symptoms can be contributed to a perceived diminished overall success in life. In turn, this can whack one’s self esteem. Problems in this area can appear as “low self-esteem” or “inflated self-esteem” or flip back and forth between them. Examples include:

POSSIBLE IMPLICATIONS

It has been said that stressors generally interact with the brain in a two-part equation. Sometimes referred to as the 20:80 Rule, this suggests that:

20% of the effect to the mind and body is due to the stressor itself

80% of the effect to the mind and body is due to one’s perception of the stressor

As the philosopher Epictetus was quoted as saying: It’s not so much what happens to us as what we think about what happens to us that makes the difference.

The 20:80 Rule, therefore, can be not only appropriate but also very helpful in a variety of situations. This can be particular true when the stressors are environmental and situational–outside of ourselves. This could include stressors such as: another’s individual’s attitude towards us, our having been fired from a job, being unable to develop a romantic relationship with a desired individual or a relationship that is clearly in difficulty. In such situations the 20:80 Rule can be of great assistance in pointing us to the value of “reframing” our perception of the stressor.

When a stressor is inside ourselves, however, and involves a mismatch between who we are innately and expectations of society, culture, school, church, and family, the ramifications may be quite different. In these cases, we so often become involved in Falsifying Type as we strive to obtain rewards or avoid punishment (e.g., shaming, invalidation of the self). Benziger believes that when considering Falsification of Type, neuroscience and experience suggest that the 20:80 Rule may need to be adjusted substantially. The Stressor (Falsifying Type) may contribute as much as 60% of the effect on the mind and body while our perception (Interpretation or Framing of the Stressor) may contribute only about 40% of the effect. The implications are profound. This would play Falsifying Type as a major and potentially life-threatening stressor!

Education, understanding, empathy, emotional support, and reframing of one’s individual experience are powerful psychological tools. Long term, however, they are basically powerless when the individual spends hours and hours each day in activities that require the brain to work up to 100 times harder, when life actually contributes to an imbalance of the brain and body, when body systems are thrown into distress by falsifying type.

Individuals who exhibit symptoms of PASS need to be evaluated for possible underlying physiological illness and (in the case of PTSD) for a history of previous trauma. They also need to be evaluated for the presence of Falsifying Type. If found to be present, they need to be assisted in identifying their own innate giftedness and helped with strategies that can reduce the adapting. The ideal, of course, is for the individual to stop Falsifying Type as soon as possible. In our culture, however, this can be easier said than immediately accomplished. In the meanwhile, understanding prolonged adapting as a significant stressor can help individuals deal with it more efficaciously.

Selected Bibliography on Falsification of Type and PASS

For those wishing to read more in-depth and technical sources, the following bibliography is recommended.

Benziger, Katherine. The Physiological and Psycho-Physiological Bases for Jungian Concepts: An Annotated Bibliography, KBA 1996.

Benziger, Katherine. Falsification of Type: Its Jungian and Physiological Foundations & Mental, Emotional and Physiological Costs, KBA 1995.

Csikszentmihalyi, Mihaly. Flow: The Psychology of Optimal Experience: Steps Towards Enhancing the Quality of Life. Harper & Row Publishers. 1990.

Hafen, Brent Q. Mind/Body Health: The Effects of Attitudes, Emotions and Relationships. Simon & Schuster / Allyn & Bacon 1996.

Jung, Carl Gustav. The Psychology of Type. London 1926.

Justice, Blair, Ph.D. Who Gets Sick: How Beliefs, Moods and Thoughts Affect Your Health. Jeremy P. Tarcher, Inc. Los Angeles, 1987.

Haier, Richard. Cortical Glucose Metabolic Rate Correlates of Abstract Reasoning and Intelligence, Studied with Positron Emission, by Haier et al. unpublished paper from January 1988.

Haier, Richard. The Study of Personality With Positron Emission Tomography in Personality Dimensions & Arousal, ed. by Jan Stvelan & Hans J. Eyesenck. Plenum Publishing Company, 1987.

Logan, Robert K. The Alphabet Effect: The Impact of the Phonetic Alphabet on the Development of Western Civilization. William Morrow and Company, Inc. New York, 1986.

Sapolsky, Robert M. Why Zebras Don’t Get Ulcers: A Guide to Stress, Stress-Related Diseases, and Coping. W. H. Freeman and Company, New York 1994.

Schlain, Leonard. The Alphabet Versus the Goddess: The Conflict Between Word and Image. Viking. New York 1998.

[1] Jung, Psychological Types, page 415.

[2] Ibid. page 415-416.

A penny saved is a penny earned.

—Benjamin Franklin

“I’m Marta,” the teenager said. “I need some tips, and I need them now!” A toss of her head sent her mane of hair flying. What must it be like to have that much hair, I wondered.

Aloud I asked, “What type of tips?”

“I get the natural brain phenomenon of downshifting,” she said. “I understand the concept. What’s more, I’ve decided half of my life has been spent in either second or first gear. I need some tips to help me upshift and stay there unless I really do fall into a pothole.”

“You’ve got the language under your belt,” I said laughing. “I’ll say that for you.”

“So how about some tips?” the girl repeated.

I looked at her more carefully. There was something I couldn’t put my finger on. She seemed just a tad too blithely persistent…

Marta noticed me watching her. “Actually,” she said, rather sheepishly, “I want to use this topic for my term English research paper, and I figured it would be smarter—and faster—to ask for your help. I promise I’ll use the tips for myself, too. Puleese!”

“Okay,” I agreed, laughing. “I’ve been asked to write an article outlining some upshifting strategies, so we’ll kill two proverbial birds with one stone.” Her sigh of relief could have been heard across town.

1. Identify symptoms you tend to exhibit when downshifted

As the old saying goes, you can only get out of trap once you recognize you’re in one. This requires some honest thought. When downshifted, people often exhibit symptoms that include sighing, defending, stonewalling, arguing, crying, yelling, avoiding, pouting, whining, fighting, bullying, isolating, over-complying, over-conforming, breaking the rules to make a statement, jumping to conclusions, taking things personally, overreacting, and so on.

The last three symptoms are especially common. Think back to the last time you jumped to conclusions, took something personally, or overreacted. Metaphorically, replay the DVD in your brain. Watch when your behavior began to go south. Now back up the DVD and re-record yourself behaving in a more functional and desirable manner. Try to identify what memories or incident(s) from your past might have set you up to respond in that way. Take another look and resolve them insofar as it is possible to do so. Picturing yourself exhibiting higher levels of emotional intelligence (i.e., choosing behaviors that provide positive outcomes) can move you toward actually doing that.

2. Identify factors that have triggered past downshifting

Triggers vary for different brains and may include the following:

Once you have defined triggers for downshifting, you can be better prepared in the future when similar situations arise. Think of it as purchasing long-term insurance. Be alert and aware. Think ahead and avoid triggers whenever possible.

3. Identify patterns of behavior you tend to exhibit when downshifted

Differing from symptoms, patterns of behavior involve the persona you typically tend to adopt when downshifted. Do you become a victim and allow people to breech your boundaries and walk all over you? Or do you become an offender, where you do that to others? Perhaps you flip back and forth between those two positions. Do you withdraw and isolate, becoming the proverbial poor-me martyr? Maybe you run away mentally and emotionally, if not physically. You might even have developed a unique pattern that combines several unhelpful and usually unattractive characteristics.

When do these patterns of behavior emerge: right away, the next day, a week later? How long do they typically last: a few moments, hours, days, several weeks? Or have they become an identity for a lifetime?

Remember that you can only manage what you label and describe. If you can’t figure it out on your own, ask a trusted friend or counselor for feedback.

4. Define what you need in order to feel safe

The process of upshifting relates to the brain’s perception of safety, just as downshifting relates to the brain’s perception of danger or fear. A perception of safety is different for different brains, although there are likely to be some common threads. Identify what you need in order to feel safe and take steps to obtain that for yourself. You may need to raise your level of emotional intelligence [EQ]. Develop competency in handling developmental tasks for your age. Think ahead and make choices that are safer for you.

Develop a metaphorical emergency kit filled with tools you can use when something unexpected happens, such as:

5. Select two upshifting strategies and pre-plan to use them

The good news is that your brain is so complex and capable that you can implement a pre-planned strategy to upshift as soon as you are aware of being downshifted. Select at least two strategies that can be used in multiple situations. The possibilities are endless. Just pick two strategies and preplan to use them. Here are some suggestions. (Note: The ones I use are the first two.)

As you implement these five strategies, you will likely find that often you can prevent needless downshifting. Such a deal!

It’s one thing to learn to upshift quickly. It’s another to prevent even the need for upshifting. This reminds me of Ben Franklin’s old saying, A penny saved is a penny earned. To paraphrase, a downshift prevented is an upshift on tap.

Laughing, Marta snapped her iPad case shut. “Thanks a bunch. It was fun killing two proverbial birds with one stone, knowing they’re still alive and all. Good luck with your article.” Tossing her great mane over her shoulder (Amazing hair, that! Red, no less) she headed for the door, calling back, “I can do this you know—both my paper and my own upshifting work.”

No doubt she could and would.

Each day of our lives we make deposits in the memory banks of our children.

—Charles R. Swindoll

“He hasn’t talked to us, except for a mumbled word or two, for nearly three weeks,” the woman said, tearfully.

“And he flunked his math test last Friday,” said the man. “Not like him at all.”

The middle-aged couple sat across the table from me. I’d agreed to meet for brunch to talk about concerns related to their 14-year old son, Jon. Their body language expressed anxiety and concern, notwithstanding the excellent food that was disappearing off our plates.

“Did he used to talk with you?” I asked, between bites of quiche.

The father nodded. The mother said, “Always.”

Silence.

“What triggered the change? Alterations in behavior never arise out of a vacuum. As one person put it, every pathology has an ecology.”

The father looked out of the window, seemingly studying the massive redwoods that reached for the sky. The mother looked at the floor, twisting the corners of her napkin.

I waited.

“Things have been a bit tense at our home lately,” the mother said finally, glancing at her husband.

Then the father spoke up, a mix of frustration and fear in his voice. “I was fired after 25 years on the job.”

I nodded.

“We began arguing over everything and nothing,” his wife continued. “A few weeks ago it escalated into a screaming match. When Jon tried to intervene, we screamed at him, too. It was as if a blind dropped down behind his eyes. It’s still there. As I said, except for answering direct questions with a word or two, he has been non-communicative.” She sighed and brushed beginning tears away.

“We blew it big time,” said the husband. “The only way is up, but we have no idea how to start the climb.”

“That’s an interesting comment,” I said, “considering you’re likely describing the natural brain phenomenon of downshifting. Yes, the only way is up but the problem is that while your behaviors can trigger downshifting in another brain, you cannot force that brain to upshift.”

I explained how the brain can be described in terms of three functional layers, which metaphorically can be thought of as gears in an automatic transmission. In the face of fear or anxiety, the brain directs its energy and attention to lower brain layers, searching for functions to help it feel safer, a natural phenomenon known as downshifting. In the process the brain also tends to stop engaging in conscious cognitive functions such as meaningful communication. “Your brains were probably downshifted,” I told the parents, “triggering the fight or flight stress response housed in the first layer or gear. You chose fight. Your son appears to have selected flight, at least from communication.”

I explained how the brain can be described in terms of three functional layers, which metaphorically can be thought of as gears in an automatic transmission. In the face of fear or anxiety, the brain directs its energy and attention to lower brain layers, searching for functions to help it feel safer, a natural phenomenon known as downshifting. In the process the brain also tends to stop engaging in conscious cognitive functions such as meaningful communication. “Your brains were probably downshifted,” I told the parents, “triggering the fight or flight stress response housed in the first layer or gear. You chose fight. Your son appears to have selected flight, at least from communication.”

No child (boy or girl) likes to hear parental arguing and fighting (much less screaming), but studies have shown that these types of behaviors tend to be harder on boy brains. Parental arguing or divorce can place boy brains at higher risk for downshifting, a situation that could seriously derail communication and learning both at home and at school. In fact, it might take several years before the boy’s brain returns to learning readiness.

“But we’re not divorcing!” the husband exclaimed.

“Does your son know that?” I asked. “With all the arguing and screaming, I’d be willing to bet he fears that divorce is the next step.”

No longer just threatening, tears now rolled silently down the mother’s face.

“We’re desperate,” said the father. “Tell us how to get his brain to upshift.”

“Therein lies the rub,” I said. “Again, while your behaviors can trigger downshifting in another brain, you cannot force it to upshift.”

The silence was deafening as the information soaked in.

“There is good news,” I continued. “Since downshifting occurs in response to fear, anxiety, trauma, or perceived threat (e.g. something that invokes a sense of helplessness in the brain), you can set up the environment to help the downshifted brain feel safer. Under conditions of perceived safety, it may upshift on its own.”

Before I offered them suggestions, however, I had something else to recommend. “I think you need to talk with your son, together, calmly and honestly. You might begin by apologizing for allowing your own fears and anxieties to express themselves in negative behaviors, like arguing and screaming. Be honest about how difficult being fired is for the male brain and talk about what you are doing to become re-employed. Reaffirm how much you love him and each other and share your hope for a positive future.”

Looking at each other, they both nodded. So we jumped into examples of potentially helpful strategies. Strategies the might help their son’s brain feel safe enough to upshift.

1. Use short, simple, positive statements.

Some believe that a portion of the 2nd brain layer or gear, (pain/pleasure center) rarely matures emotionally beyond the age of a four- or five-year-old child. Think about the ways in which you communicate with a child of that age. Short, simple instructions are usually most effective. This is not “talking down” to the person. Rather, it is recognizing that this style is likely to be more effective when communicating with a brain in a downshifted state.

Positive statements involve a one-step process. What you picture is what you get. Negative statements, the reverse of an idea, require a two-step process. The brain must change the first picture by imagining the opposite. The 3rd brain layer generally is capable of this, although speaking in negatives is not as effective as speaking in positives. This process is almost impossible for a child’s still-developing brain to pull off, however.

When the subconscious brain tries to process negatives (e.g., Don’t touch the stove), the brain initially creates a mental picture of touching the stove and may miss the word don’t. It is usually more effective to say, Keep your hand away from the stove. Negative comments, instructions, or thinking patterns can derail communication as the brain mentally pictures negative outcomes and may or may not create opposite pictures successfully.

2. Use present tense verbs.

All three brain layers can perceive and respond to present-tense language. (The subconscious layers likely respond to and follow the mental pictures the language created in the 3rd brain layer.) So regardless of which brain layer has the focus at that moment, communication can be perceived.

For example, say “Put your homework in your backpack now.” Avoid saying Don’t forget your homework or Remember to take your homework in the morning. Those are future tense statements, which may or may not be recalled in the morning.

3. Use congruent communication.

In order for the content of the communication to be transmitted clearly and effectively (to avoid mixed messages), the words, voice tonality, and nonverbals need to be congruent—in harmony, matching, coinciding with each other. If the conversation is serious, use serious facial expressions. If communication is happy or in fun, smile.

Congruent communication requires honesty. In a two-party communication, the message that comes across with the most impact will usually align with what you really think or feel. The truth will leak out in tone of voice and body language, regardless of the actual words you use.

4. Avoid asking the Why-question.

In many languages the word why can be perceived as stressful or threatening. It can imply an expectation that you should have done something different from what you actually did, and can create just enough anxiety to trigger downshifting. The response to “Why did you do that?” or “Why didn’t you do that?” is often a shrug or a mumbled Don’t know. And the brain likely does not know. It might be able to come up with some ideas that could have some bearing on the issue at hand, but in most cases not anything objective and definitive.

Use other words to elicit information or stimulate discussion. Try instead:

5. Sit down when conversing.

When both parties are at eye level. the fear and anxiety potential can be reduced. In addition, studies have shown that when both parties are seated the brains tend to perceive time differently, often estimating more time passed than actually went by. Speak in a calm, steady, moderately-pitched voice. Listen to the words the other person uses, watch his or her body language and mirror the other person’s words and communication style—auditory, visual, or kinesthetic.

If the person says, “That’s unclear to me” (which might indicate a visual sensory preference), a reply such as “Well, let me try again and see if you can hear what I’m saying” (auditory sensory preference) or “You need to get a handle on this so pay attention (kinesthetic sensory preference) will likely sound foreign and uncomfortable to the other brain. The brain tends to feel safer and more comfortable when it perceives both parties are speaking the same language, sensory as well as linguistic.

6. Solicit the other person’s input.

Listening can promote a feeling of being heard and even understood, whether or not you agree with the perspective. Even when you differ, it’s not always helpful or even necessary to point out areas of disagreement. If possible, try to identify commonality, even if there are areas of disagreement. Sometimes you can agree to disagree because it really doesn’t matter.

Ask yourself, “Will this make any difference twelve months from now?” If the answer is no, avoid wasting time and energy on it. Sometimes you can just agree to disagree. If the answer is yes, then negotiate to consensus, understanding that the solution will work only partially for both parties and there will need to be areas of compromise.

7. Provide options for making choices.

The brain feels safer when it can choose and make a decision. Whenever possible allow the other person to choose between two options—never more than two at a time because the brain only has two cerebral hemisphere). Select options whether either is fine with you, and simply offer both as a way to help the other brain choose and feel safer.

They can be simple options: “Will you take the chair or the stool?” “Do you prefer water or 7-Up?” “Do you want the door open or closed?”

Buy-in often can be enhanced by a sense of participation. If there is no option at the moment for an entire decision, provide the other person with an option to exercise some control over part of an activity if not over the entire activity.

“How far the brain downshifts and when and if it upshifts depends on the degree of threat that brain perceives,” I reminded them. “Just keep using the strategies and avoid behaviors that are known to be high risk for triggering downshifting.”

They left, hand in hand, smiling. Granted, the smiles were a bit tenuous but they were there. I felt hopeful for Jon. For them, too, for that matter.

If the brain were so simple we could understand it,

we would be so simple we couldn’t.

—Lyall Watson

“My teacher says the triune model of the human brain, described by Dr. Paul MacLean in the 1960’s, is an oversimplification.” The young man’s chin was outthrust, his body language muscularly defiant. “What do YOU have to say?”

“That I agree. In fact, one of the pluses of the model is its very simplicity, which in turn can be helpful due to its broad explanatory value. Your teacher’s comment reminds me of a favorite quote: If the brain were so simple we could understand it, we would be so simple we couldn’t.”

“So what’s the point in talking about it?” he persisted, albeit less belligerently.

“My brain’s opinion is that knowing something about brain function, even through the use of a simple metaphor, is better than not understanding even that much,” I replied, “especially since brain imaging techniques have provided a glimpse into clusters of brain structures that contribute key brain functions.”

“Like knowing what?” the young man asked.

“Like knowing that the cluster of brain structures associated with the Cerebrum or 3rd brain layer involve high-level cognition that contribute functions such as planning, modeling, simulation, and a sense of humor. Like knowing that structures associated with the Mammalian or 2nd brain layer involve functions related to social and nurturing behaviors, mutual reciprocity, and memory. Like knowing that structures related to the Reptilian or 1st brain layer contribute basic functions that help keep you alive, involve territoriality, and that load and run ritualistic behaviors and motor sequences, including those that allow you to play video games—plus stress reactions such as fight-or-flight, conserve-withdraw, and tend-befriend.”

“But I thought that part of the brain was nonconscious,” he said, perking up.

“Good job,” I replied. “It is. Obviously you know something about the brain.” The young man smiled. “Although more has been learned about the brain in the last hundred years or so than was known in all the preceding eons, the information brush is still fairly broad.” Knowing he was an IT major, I added, “According to Caltech professor John Doyle, in the world of hardware and software, where everything is known about both systems, their functionality only exists by both realms interacting, yet, no one has captured how to describe that reality. That goes for the brain, too, at least in my book.”

“Okay, I’m in,” he said. “Lay the layers on me!”

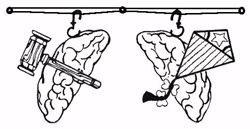

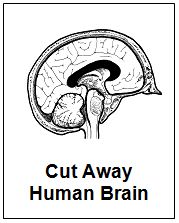

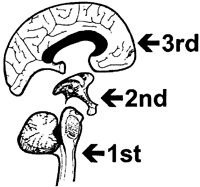

Laughing, I showed him drawings of the triune brain. A cut-away in the picture on the left and separated layers for easier identification in the box to the right. Although all layers interact at some level, each also contributes distinct functions. And when you think of the layers as gears, that can help you better understand the natural brain phenomenon of downshifting. Then I distributed a summary list of key functions that each brain layer is thought to contribute.

Also known as the reptilian brain, R-complex, energy brain, and sensory-motor brain, it contains the brain stem, cerebellum, and connections to the spinal cord and houses nonconscious functions

Caveats:

Functions:

According to Joseph Chilton Pearce in his book The Biology of Transcendence, this portion of the brain can take over the physical components of a learned skill, which frees the neocortex to observe and develop ways to improve performance. On its own, the reptilian layer is unable to alter inherited or learned patterns of behavior.

Also known as the mammalian brain relational brain, limbic system, and pain-pleasure center, it houses nonconscious functions. It consists of a rim of cerebral cortex on the medial surface of each hemisphere and includes a collection of relatively small brain organs including: two amygdala, mammillary bodies, cingulate gyrus (above the corpus callosum) the parahippocampal gyrus (in the temporal lobe below) and two hippocampi, which serve as the brain’s search engine

Caveats:

Functions:

Also known as the cerebrum, gray matter, cortex or neocortex, and cognitive or thinking brain, it houses both nonconscious and conscious functions. Estimates are that conscious functions may account for 20% of its size. It is divided by a natural fissure into two hemispheres, that are in turn are divided by natural fissures. This results of four cerebral divisions with a total of eight lobes.

Caveats:

Functions:

That’s the triune brain in a nutshell. As an aside, Arthur Koestler made the concept of the triune brain the centerpiece of much of his work in The Ghost in the Machine, while English novelist Julian Barnes mentioned the triune brain in the foreword to his 1982 novel Before She Met Me.

By the way, Dr. Paul MacLean’s recognition of the limbic system as a major functional system in the brain eventually won wide acceptance among neuroscientists. The triune brain model is regarded by some as his most important contribution to the field, even though everything he deduced hasn’t proved out as he envisioned it might.

“Good job!” said the young man as he walked toward the door. “I get the layers or gears. That’s really helpful.”

I figured that was high praise from his brain.

Fear of any type shuts down higher modes of awareness and throws the brain into an ancient survival mentality.

—Joseph Chilton Pearce The Biology of Transcendence

Marilee propped herself on one elbow and said, “I swear you never told me that!” Her face was twisted with pain because of “my awful headache,” as she put it.

The patient had been admitted to the hospital after being involved in a multiple-car accident. A relatively common side effect of one test was headaches. And now, after having given the physician informed consent and having signed the hospital consent form providing permission to proceed with the test, Marilee was angrily proclaiming to one and all that nobody had told her about the possibility of post-procedure headaches.

This type of scenario is not relegated to the healthcare environment. It occurs everywhere in everyday life and can form the basis for misunderstandings, controversy, arguments, and litigation. What is happening in the brain when a person says, “You didn’t tell me that?” Especially when you are as sure as you know your own name that you did!

Knowing about the natural brain phenomenon of downshifting can not only help you understand what may be happening in these types of situations but can also assist you in implementing strategies to resolve downshifting quickly, improving the odds that communication will get through and recall occur.

Although not all researchers use the term downshifting, I prefer it because my brain can connect this information to something it already knows—an automatic transmission. When the going gets tough and you are driving a vehicle with automatic transmission, it automatically shifts down to a lower gear. When the going gets easier, it automatically shifts back up to a higher gear. Serious consequences can accrue if the vehicle’s transmission fails to upshift as expected, ranging from needing more time and fuel to reach your destination, being a potential hazard to other drivers, and increased wear and tear on the engine—if not outright damage.

A similar situation can occur in the brain. Downshifting results in an automatic shift of attention and energy away from higher brain layers toward the lower brain layers. Furthermore, it can even do so in a nanosecond and outside of conscious awareness.

Metaphorically, think of your brain in terms of three functional layers—or gears. Although they interact continually, each is believed to contribute distinct functions that help you navigate along the highway of life. The drawing of the human brain at the right depicts these three layers/gears.

Metaphorically, think of your brain in terms of three functional layers—or gears. Although they interact continually, each is believed to contribute distinct functions that help you navigate along the highway of life. The drawing of the human brain at the right depicts these three layers/gears.

3rd layer or gear – Known as the neocortex (or new brain), this brain layer houses conscious rational-logical thought and executive functions, as well as subconscious thought; can perceive positive as well as negative statements (although positive instructions are easier to follow); and processes the present, past, and future.

2nd layer or gear – Known as the mammalian (or emotional brain), this subconscious layer includes the (so-called) pain/pleasure center, generates emotional impulses, directs immune system function, perceives positive statements, and processes the present and past.

1st layer or gear – Known as the reptilian (or action brain), this subconscious layer includes survival and stress-reaction reflexes, perceives positive statements and the pictures they generate in the brain, and processes the present only.

That’s true! Even a good thing—taken to the extreme—can lose some of its helpfulness. Just as with a vehicle’s automatic transmission, there are positive and negative consequences related to downshifting in the human brain. When downshifting is activated frequently or sustained for a prolonged period, learning and development can be impaired in children; and thinking, learning, and decision-making can become faulty in adults. Communication can be hindered if the sender, the receiver, or both are in a downshifted state. This information can be especially important for healthcare professionals, whose services are often sought by individuals in crisis (e.g., those who have experienced trauma, are fearful, or are in emotional or physical pain).

Estimates are that people may recall less than 15% of what is told to them during a crisis. When the brain is downshifted through fear, anxiety, or worry, you may be prevented from learning cognitively, react more automatically (reflexively and instinctually), and be resistant to change. Consequently, it should come as no surprise that Merilee’s perception was “You never told me that!” Her brain had likely been in a downshifted state due to the recent trauma, along with some measure of anxiety about testing procedures and ultimate recovery.

In general, the brain tends to downshift in situations that involve trauma, crisis, or any type of fear—worry and anxiety representing forms of fear.

You can be proactive in learning how to prevent unnecessary or prolonged downshifting:

1. Develop a high-level-wellness lifestyle

In general, the brain tends to work more effectively when its owner is living a high-level-wellness lifestyle in balance. This can help you prevent periods of exhaustion. For every period of exhaustion, the brain tends to experience a corresponding period of depression. While depression in and of itself may not be a trigger for downshifting, it can drain your energy and increase your risk of being challenged in areas that you find difficult or energy intensive.

2. Create a loss history and engage in appropriate grief recovery, as needed

Unresolved loss can create internal tension, anxiety, and even fear. Write down your loss history. The starting date may be prior to your birth in some cases (e.g., you were not a wanted pregnancy). Evaluate your loss history carefully and engage in appropriate grief recovery as needed. Refer to Taylor’s website for information about the Grief Recovery Pyramid for survivors of loss, as opposed to the Kubler-Ross model for individuals who are personally facing death. Dealing with loss effectively can help prevent unnecessary downshifting.

3. Give up blame that is related to downshifting

Recognize that downshifting is a natural phenomenon that tends to occur automatically and is largely subconscious. It is a desirable short-term “fix” for the brain to access behaviors and reactions that it perceives are safer. Even if you downshifted unnecessarily or stayed down too long, avoid beating up on yourself. Most people (that includes you!) do the best they can under the particular circumstances with their level of understanding and the tools that are available to them. Blaming can create anxiety, which might trigger downshifting. Blame is a red herring that never fixes anything. Avoid it. Just learn from your experiences and do better next time.

4. Increase conscious awareness

Perhaps 90-95% of what goes on in the brain occurs at a subconscious or nonconscious level. You can manage only what you become aware of and can label and describe. It’s often what you don’t know you don’t know that can trigger dissention, anxiety, and downshifting. Become more observant and increase your conscious awareness of both your external and internal worlds.

5. Develop an appropriate response to conflict situations

Perceived conflict, especially if fear is involved, can trigger downshifting. Just anticipating the possibility can be enough. Avoiding conflict (when possible) is being smart. Running away from unavoidable conflict is not. The mature, responsible approach is to take careful and deliberate steps to resolve conflict in a timely manner rather than creating a metaphorical enemy outpost of unresolved conflict in your head. Managing conflict successfully may involve using tools such as reframing, forgiving, setting bona fide boundaries, raising your emotional intelligence, and changing your thought patterns and mindset, to name just a few. Metaphorically, build yourself a conflict toolkit and carry it with you inside your brain.

6. Take responsibility for upshifting

No one can upshift your brain but you. Understand that upshifting occurs through a conscious process. Develop at least two preplanned strategies, then take responsibility for implementing them the moment you recognize your brain is downshifted. Any number of strategies work well. My favorite two are these:

7. Develop an affirming communication style toward yourself and others

Negativity, impatience, worry, anxiety, or fear can act as a trigger for downshifting, actually delaying personal growth, learning, and needed recovery processes, if not addressed and resolved. This is especially true when new, more functional patterns of behavior are in the process of being developed and are not yet strong enough to override the older, less desirable patterns. Speak, think, and act in an affirming manner. Follow the old adage, Fake it ‘til you make it! Then watch more desirable behaviors emerge and become the norm.

You need the benefits that appropriate downshifting can provide: virtually instantaneous access to survival mechanisms and stress responses. You also can benefit from preventing inappropriate downshifting and from avoiding staying downshifted longer than absolutely necessary.

Using this natural brain phenomenon appropriately can help you live life more safely, smoothly, and effectively.

That’s good for everyone. And every little bit helps!