You will recognize your own path when you come upon it, because you will suddenly have all the energy and imagination you will ever need.

—Jerry Gillies

The woman stalked into my office pushing a wall of vibrating emotion in front of her. Without as much as a howdy-do she launched her voice into the stillness.

“My auntie,” she began, “attended one of your presentations and came home telling me that you said empathizing and systemizing brains describes a Bent. And I am here to tell you that I am not Bent. Neither do I have a Bent! Moreover, I never intend to be BENT! BENT is NOT a PLUS!”

The woman was obviously bent on a mission.

Quite frankly, besides the words that were virtually cannoned in my direction, the first thing I noticed was her chin—stuck way out in front, if you know what I mean.

Before I could craft an appropriate response, however, the woman continued. “And where does the word Bent come from anyhow, and how could it possibly apply to people? Trees are Bent.”

“Correct,” I responded, pleasantly. “Trees sometimes are bent. In the context of brain function, however, a bent is a plus!” I paused to watch her reaction. “Regarding the brain, a bent refers to the natural talents your brain possesses based on its innate giftedness.”

She stared at me for a long moment. Pulling in her chin (at least fractionally), she said, “I’m Francie, and I’m rarely wrong.”

“That may be one of your talents, your bent,” I said, smiling. “In some ways it would be marvelous to rarely be wrong—although you might be rather unpopular if you publicized that talent.”

“Well, what about this business with empathizing and systemizing? I suppose you have some highfalutin explanation for them, too.”

“Nothing highfalutin,” I replied, chuckling. “They are foundational words. Empathizing relates to one’s ability to identify and understand the thoughts and feelings of others, to respond to them with appropriate emotions, and strive to be harmonizing in relationships.”

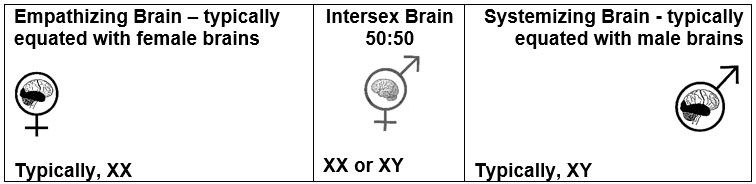

I noticed Francie glance away, a bit self-consciously I thought. Nevertheless, I continued. “Systemizing relates to one’s strength of interest in systems, especially in analyzing or constructing or organizing them. Although humans are a mix of both, in most cultures, if not all, empathizing brains are equated with and assumed to be linked with female brains, while systemizing brains are equated with and assumed to be linked with male brain.”

“Ah-ah!” Francie nodded, vigorously. “I told you I was rarely wrong. You’re labelling females as harmonizers and defining males as organizers.”

“Is that what you heard, Franci?”

“That’s exactly what you said.”

Feel free to take a seat, Francie,” I said. “Take your pick: stool or chair. I have a chart you might like to see.” I unrolled a piece of paper about 6 inches high and 12 inches wide and smoothed it out on my desk. “Although human brains are more alike than they are different, there are some differences. Males and females have identical hormones, for example, just in different ratios. Males tend to have more testosterone and females tend to have more estrogen. In a similar way, both male and female brains contain empathizing and systemizing functions. However, many females tend to lean more to empathizing while male brains tends to lean more twoard systemizing. Interstingly, some large sampte studies have reports that female brains are through to be more empathizing because they talk about what they are doing for others, while male male brains tend to help those they believe need and are diserving of health without saying a word about what they are doing.”

Francie pursed her lips and then looked back at the picture. “There are also a small percentage of brains that are believed to be 50:50 in terms of empathizing and systemizing,” I continued. “Dr. Simon Baron-Cohen has estimated that 95% of the world’s population can be portrayed in this pictorial representation.”

Male-Female Continuum

“Well,” Francie said—a bit belligerently I thought, “I am very interested in systems. Are you trying to label me?”

“Hardly,” I responded, chuckling. “In the first place, male-female research tends to be reported in the form of generalizations, conclusions that follow the Bell Curve of Distribution and typically apply to at least two thirds of the population but not necessarily to all.”

“I know,” Francie broke in. “I am not a typical female. So, what’s wrong with the research?”

“Individual differences don’t invalidate the research—they just exemplify individual uniqueness. There has never been a brain like yours on this planet, and there will never be again. In part because every thought a brain thinks changes its structure and no one thinks the same exact thoughts. Osho pointed this out, saying:

From the very beginning you are being told to compare yourself with others. This is the greatest disease; it is like a cancer that goes on destroying your very soul because each individual is unique, and comparison is not possible. I am just myself and you are just yourself. There is nobody else in the world you can be compared with.

I paused. Francie nodded.

“No human being is 100% empathizing or systemizing. Females who are primarily empathizing can still be organized, follow step-by-step instructions, and may be analytical and interested in systems. Males who are primarily systemizing can still be empathetic, identify and try to understand the thoughts and feelings of others, respond appropriately to emotions, and strive to be harmonizing in relationships.”

By being yourself, you put something wonderful in the world that was not there before.—Edwin Elliot

“I love studying the science of brain function,” I added, “Can you tell?”

“Oh, I can tell,” said Francie, and what might pass for a smile (but which looked more like a snear) crossed her face, briefly. “So, who is better at multi-tasking? Let me guess: females!”

“Interestingly, studies have shown that the human brain is not designed to multi-task,” I said. “Attempts at multi-tasking make the brain function less efficiently. Both error rates, fatigue, and accidents rise with attempts at multitasking. Having said that, systemizing brains are able to ‘simultask,’ meaning that they can do two different tasks at the same time—simultaneously— as long as each task is directed by a different hemisphere.”

“Go on with you!” said Francie. “Now you are scaring me!”

“A male can be assembling a toy for his grandson using his right hemisphere and do so without reading the instructions, while at the same time he is holding a conversation with his left hemisphere on a totally different subject. Female brains do not simultask. They can do rapidly-alternating shifts of attention and do that reasonably well, as long as they are only doing two tasks. More than that and error rates rise significantly.”

Francie’s body language was showing signs of relaxing and her hands were no longer tightly clenched, her knuckles no longer white. I took a risk. “I grew up in a family system where boys were considered more important than girls. And where what a girl was permitted to do fit into a much narrower band of options as compared to that of a boy.”

I got no further when . . . “You have NO IDEA!” Francie blurted, heatedly. “I have seven brothers. My mother died when I was nine, and my dad never remarried. From then on I heard over and over that I was only good for the cooking, cleaning, and domestic chores. It made me so mad. I told them once that anything they could do I could do better!”

“Wow!” I exclaimed. “Nine years old and you took over cooking, cleaning, and domestic chores? I bet few girls that age could have pulled that off. You must have multiple bents!”

I had to smile, and this time, wonder of wonders, so did she. “So, what about setting and achieving goals?” she asked.

“All brains can set and achieve goals, and they do. Generally, however, systemizing brains may be more goal oriented. Females can absolutely be goal oriented, however they are also experience oriented. They tend to care how their goal orientation is impacting their relationships. Systemizing male brains have been known to be somewhat oblivious to anything but whatever will help them achieve their goal. This can cost them dearly in terms of relationships.”

You would not exist if you did not have something to bring to the table of life.

—Herbie Hancock

“And emotions?” Francie asked.

“Research suggests that males and females both can experience emotions deepy. What differs is they way emotions are expressed. Empathizers are more likely to express emotions verbally and with body language such as tears. Systemizers tend to express their emotions more through actions than words. You know, like kick the cat, get drunk, go out and crash the car. Some studies have shown that males tend to exhibit anger even when they are fearful or sad; females tend to exhibit fear or sadness even when they are mad. This may be due to a combination of factors including socialization.”

Francie looked at her watch. “One more question. For now. Tell me about males versus females and competition. My brothers compete for everything and about everything—except about doing anything to help around the house, that is. I swear, it’s like pulling hen’s teeth to even get them to carry their dirty dishes into the kitchen. Selfish creatures, my brothers.”

Everybody is a genius. But if you judge a fish by its ability to climb a tree, it will spend its whole life believing that it is stupid.

—Albert Einstein

“Competition, is it?” I asked. “That is a complicated question because several things play into the level of competition that matches a person’s comfort zone. Compared to empathizers, systemizers tend to be more competitive against others—unless empathizers are competing against others for the attention of a systemizer. By any chance are you comparing yourself to a stereotype?”

Francie burst out laughing. It had a delightful, bubbling sound.

“A person’s level of extroversion also impacts competition. The higher one’s extroversion bent, the more likely that individual is to gravitate toward competition.

I went on. “In addition, testosterone levels appear to potentiate both competition and assertiveness. Since males tend to have higher levels of testosterone, they tend to exhibit higher levels of both assertiveness and competitiveness. And if they have just played an exciting game or even watched it on TV, their testosterone can shoot up rather dramatically, something that appears not to be universally true in empathizing brains.”

“Do I ever know about that!” exclaimed Francie. “More than once my brothers significantly altered the décor in our family room after they disagreed about which team should win. They never seemed to hold any grudges, however. And they DID pick up after themselves. My dad was adamant about my NOT having to clean up after they had a food fight or tried to bash each other’s brains.”

This time is was my turn to laugh out loud. “I only had one brother—although he had plenty of testosterone! In the main, I typically enjoy relating with systemizing brains. I enjoy the differences and their uniqueness. None of these difference or tendencies or bents locks you into functioning in a specific style. That boils down to personal choice”

You are as amazing as you let yourself be. Let me repeat that. You are as amazing as you let yourself be!

—Elizabeth Alraune

“Hmmm-mm,” she mused. “If I am honest, I think I have allowed expectations to lock me OUT of some behaviors and responses that align better with who I am innately, a woman with more of an empathizing bent. But perhaps somewhat less empathizing if compared with some female brains.”

“Yeah, well, it can happen,” I replied. “The great news is that as you learn more about the brain in general, and yours in particular, you can choose how you want to respond.”

Francie gathered up her things, ready to leave. “Could I come back and talk with you again sometime?” she asked. “I think my brain likes yours.”

Absolutely!

Chin in, she left, apparently now on a new kind of mission: a mission to celebrate her own unique bent!

Historically and traditionally, established religion (often symbolized by cathedrals) has at once offered solace and retreat and promoted discord and controversy. For individuals deeply committed to a spiritual life, these seeming contradictions have often proved frustrating, if not problematic. Either way, they are a great pity inasmuch as the initial motivation for even establishing religion may have been to provide succor, contemplation, companionship, and accord.

As with politics, religion is often discussed with either virtuous vigor or abject sarcasm. Between those two poles falls a spectrum that stretches from blind obsession to coercive torture. One trigger for controversy can be a failure to separate the concept of religion from that of spirituality. As one observer put it somewhat tongue in cheek, Religiosity is for those who don’t want to go to hell; spirituality is for those who have been there and don’t want to go back.

In the past few decades, research on the human brain, has offered insights into brain differences and provided reasons that these differences are not only innate but important to achieving a whole society. Emerging brain-function studies now theorize that every brain on this planet is different—in structure, function, and perception. Viewing individual innate preferences as equal in value although unlike can free individuals to embrace activities and processes that work for them, to internalize the right of each person to do the same, and to experience enrichment through the observation of and/or the participation in endeavors outside their own areas of preference. Viewed within this framework, differences can take on new meaning and the discovery journey can be stimulating.

The human cerebrum is divided naturally into four divisions, each of which makes an important contribution to life. Each individual is believed to possess a biochemical preference in one division over the other three. As such, an individual’s natural bent or energy-efficient way of doing things would reflect his or her division of giftedness or innate energy advantage.

Table 1 The Purpose of each Cerebral Mode

Prioritizing Division (L frontal lobe) Enables you to develop skills to set and achieve goals, and make objective and timely decisions, which include:

| Envisioning Division (R frontal lobe) Enables you to develop skills to anticipate and make changes, which include:

|

Maintaining (L Lower Division) Enables you to develop skills to produce and supply services (dependably) for maintaining life and work, which include: The ability to sequence a set of actions into a routine (set of premade decisions) and follow it accurately The tendency to more easily absorb information that is perceived as linear (e.g., rectangles, squares, lines, angles)

| Harmonizing (R Lower Division Enables you to develop skills to build trust, harmony, connection, and peaceful foundations, which include: The ability to compare everything to assess for the presence or absence of harmony The tendency to more easily absorb information that is perceived as harmonically related (e.g., color, smiles, body language, oval or circular or rounded shapes)

|

Human beings have differing needs for stimulation or protection from stimulation. This leads some to be gifted at working in the melee and others to be gifted at working alone. This can be plotted on a continuum with Extraversion and Introversion at opposite ends and Ambiversion in the middle. (See table below with estimates of population groupings.)

| Extraverts 15% | Ambiverts 70% | Introverts 15% |

These differences naturally influence the way in which individuals prefer to worship. Some (e.g., Introverts) may be more comfortable worshipping alone, with only a few others, or in a quiet secluded setting. Others (e.g., Extraverts) may prefer just as naturally to be in noisy, crowded, or stimulating settingswhere the action is. The Ambiverts are most comfortable in situations that provide a moderate level of stimulation.

Human beings also have unique preferences with respect to the way in which they experience life. In Western cultures these are often referred to as the visual, auditory, and kinesthetic (including touch, taste, and smell) sensory systems. Unimpaired, each individual can use all three systems, although one type of sensory stimuli will register most quickly and intensely in the brain.

If one’s sensory preference is not acknowledged and provided for, the individual may miss taking in valuable data, may conclude that the experience was unhelpful or not meaningful, or may even experience discomfort.

As I child I puzzled over there being four gospels (Mathew, Mark, Luke, and John). Four different accounts written by four different authors and emphasizing different aspects of life at that time of the world’s history. Looking at the four Gospels in Scripture.

Although admittedly conjecture on my part, in adulthood I’ve come to theorize that each author may have had a different brain bent and might have written in his own brain’s “language.” A reader might, therefore, based on personal brain bent prefer one of the gospels over the others. Using one model of authorship, each gospel can be compared with key brain characteristics and correlated with groups of individuals who were represented during that period of time (see Table 2).

Table 2 – One way to view Gospel authorship and the four cerebral divisions

A physician (Prioritizing Division)

The Zealots: a somewhat fanatical sect with the avowed goal of repelling Roman domination. | The first gospel writer (Envisioning Division)

The Essenes: a monastic brotherhood that lived in seclusion and prepared the Dead-Sea Scrolls. |

A tax collector (Maintaining Division)

The Pharisees: a group that, in an effort to do things correctly, emphasized strict observance of rites, oral traditions, and ceremonies. | The beloved apostle (Harmonizing Division)

The Sadducees: a dislike of conflict led to compromise, which eventually resulted in the loss of hope and in differences of belief. |

According to historical accounts, Mark was the first gospel writer. Envisioners are often on the innovative edge and the fact that Mark was the first to write a gospel account correlates with that tendency. This suggests that he was visionary and, perhaps before others, could see the Church that was to develop. Mark begins with prophecy and speaks primarily of the mystical and metaphorical doings and words of Jesus. His emphasis is on the wonder of Christ’s existence and ministry. Although his is also the shortest record, he includes some interesting details related to miracles and parables that are not included in the other three gospels.

Matthew, a tax collector, wrote an historical narrative. His gospel has a flavor of the Maintaining division beginning as it does with a list of ancestors. Matthew presented Christ as a teacher who came to show people how to behave. From the Sermon on the Mount through information on divorce, loving one’s enemies, and judging others to the fallacy of worrying and the proper way to pray, the emphasize was on helping people learn how to do it right. Matthew is the only gospel writer who reports several sermons in detail, in their entirety.

The Apostle John wrote of connection and faith in the gospel, and emphasized the coming of the Comforter. History has referred to John as the disciple Jesus loved. John presented Christ as connected to God, as being one with God. He also referred to Christ as the Word of God an approach that underscores the personal, relational, and one-to-one communicational aspect perceived by the writer. This focus on unity and connection reflects strong Harmonizing preferences and values.

Luke was a physician. Although physicians were often shamans in Biblical times, as an author, Luke recorded facts after a thorough investigation. Likely a Priorizer, he begins his account by saying, “Since I have investigated all the reports in close detail, starting from the story’s beginning, I decided to write it all out for you . . .” (NIV). His words are reminiscent of inductive/deductive reasoning, a function of the Left Frontal Lobe. Luke used a variety of medical terms (e.g., pregnancy, circumcision, high fever). This writer also traced Christ’s ancestry through a genealogy of fathers and sons back to Adam, ending with Adam being the “Son of God.” In terms of who’s who, this suggests that hierarchy was important to Luke and that possessing a royal bloodline or lineage was significant to proving value.

Four different gospels, written by four different authors, and emphasizing different aspects of Bible times. Individuals who clearly have a favorite gospel may enjoy the one authored by a writer whose thinking style most closely resembles that of the reader.

According to the parable of the talents as recorded in the Gospel written by Matthew, every human being possesses special giftedness. Several passages of scripture refer to special spiritual gifts (1 Corinthians 12-14; Romans 12:1-8; Ephesians 4:1-16; 1 Peter 4:8-11).

Reviewed in the light of brain lead, society and culture does not necessarily honor all giftedness equally. For example, the gift of hospitality isn’t rewarded in the same manner as is the spirit of prophecy; the gift of serving others is not rewarded in the same manner as is the gift of raising money. (It is recognized that some religions teach that a specific spiritual gift may be “given” to an individual due to a need in a specific situation regardless of the individual’s innate giftedness.)

Table 3 – Spiritual Gifts and Brain Lead

Prioritizing Division

| Envisioning Division

|

Maintaining Division

| Harmonizing Division

|

* I. K. Benziger PhD also theorizes that each mode houses a wisdom potential that can increase with maturity, skill development, and overall integration of brain function. This differs from “King Solomon’s wisdom,” so-called.

As a concept separate from affiliation with religion, one’s individual spiritual journey is impacted by brain lead. That is, individuals may approach personal spirituality differently based on their innate giftedness (see Table 4). Their actual behavioral choices (as compared to their innate preferences) may, of course, be moderated because of past experience, education, and expectations.

Table 4 – Approach to Spirituality

Prioritizing Division Innately may tend toward:

| Envisioning Division Innately may tend toward:

|

Maintaining Division Innately may tend toward:

| Harmonizing DIvision Innately may tend toward:

|

If individuals choose to affiliate with a religious denomination and participate in the organization, they may gravitate toward different types of activities, again based on innate brain lead.

Table 5 – Religious Participation Preferences

Prioritizing Division

| Envisioning Division

|

Maintaining Division

| Harmonizing Division

|

Admittedly one’s preference for style of religious service (if one attends corporately) can be developed through expectation and exposure. In adulthood, however, if the individual is owning and following his/her brain bent, preference can be impacted by one’s own innate giftedness. Individuals with a preference for using one of the left cerebral division tends to gravitate toward a different style of religious service compared with those who prefer to use one of the right cerebral divisions.

Table 6 – Worship Style Preferences by Cerebral Mode

Prioritizing Division

| Envisioniing Division

|

Maintaining Division

| Harmonizing DIvision

|

These summarized examples of differences (Tables 4, 5, 6) also have an impact on the controversy between so called traditional and celebration worship services. Indeed, one might generalize by saying that the major differences between these two styles reflect the general division between the left hemishere clergy and congregations and right hemisphere clergy and congregations.

Typically, traditional services in our culture emphasize what people need to DO to live sanctified lives. In these congregations there is usually an emphasis on obeying rules and regulations, attending church regularly, reading/memorizing scripture, and on the doctrine of sanctification (choosing to live daily lives without making a habit of sinning). Individuals who have a preference for a left-brain thinking style (with a brain bent in either the Prioritizing or Maintaining division), often prefer to attend traditional church services. They like their services to include a preponderance of activities that match that portion of the brain.

On the other hand, people who prefer to use functions that derive from the right hemisphere of the brain (with a brain lead in either the Envisioning and Harmonizing divisions), often prefer to attend celebration church services. In such congregations there is usually an emphasis on trust, grace, loving one another, and on justification (accepting God’s free gift of grace) over sanctification. Entire congregations have been splintered into factions because of conflict over these differences (see Table 7).

Table 7 – Traditional versus Celebration Service Styles

Prioritizing &Maintaining Divisions

| Envisioning & Harmonizing Divisions

|

The Apostle Paul was evidently somewhat disturbed by the fact that many communities of early Christians were plagued by conflict. He saw it as counter productive to the primary purpose of Christianity and exhorted his various flocks to avoid it (Titus 3:9). Next to the four Gospels, the Apostle Paul is arguably the most distinguished Biblical writer and early expert on what it means to be a Christian. The writings of Paul, filled with observations, exhortations, and advice are included within the New Testament. And yet, notwithstanding, the conflicts that so distressed Paul continue to divide Churches today.

For example, Pastor Bob (not his real name but a true story) unwittingly found himself in the middle of one of these controversies. It seems that he had become accustomed to delivering his sermons as close to his congregation as possible. Bible in hand, wearing a lavaliere microphone, he sometimes even walked right down into the aisles amidst the seated members. He really enjoyed preaching eye to eye. His genuine interest in nurturing, encouraging, and affirming his flock was obvious. He wanted to help each one to develop a personal relationship with God.

Pastor Bob eventually accepted a call to pastor a large church in another state. The pulpit at his new assignment was immense. Creatively carved in solid oak, it dominated the rostrum. Being rather short of stature, he not only felt dwarfed by the pulpit but totally separated from the congregation, as well. Therefore, he soon enlisted the help of a couple of deacons who moved the imposing pulpit to one side of the platform. Alas, he was unprepared for the storm of protest that ensued the next weekend.

At the conclusion of the morning sermon, several individuals accosted Pastor Bob. Joe, a man with a preference for the Maintaining division, actually looked stressed as he said, “The pulpit has been in the center of the platform for years and years, ever since I was a little duffer. It’s just not right to change its location!” Derek, an individual with giftedness in the Prioritizing division asked pointedly, “Who gave you permission to move the pulpit?” Of course, the few individuals with an Envisioning bent thought Pastor Bob’s innovation was a welcome change, but they were definitely in the minority. Those with biochemical preference in the Harmonizing divisioin were decidedly uncomfortable with the whole situation. In an effort to preserve harmony they agreed with first one parishioner’s opinion, then with another. The perceived conflict and lack of harmony contributed to each parishioner finally going home with a splitting headache.

After numerous phone calls, the church-board chair called a meeting of the august committee. After three hours of heated discussion the don’t move the pulpit contingent prevailed. The following week Pastor Bob arrived at church to find the pulpit returned to its original position and firmly attached to the platform. For the next few weeks the atmosphere was strained, to say the least.

Fortunately, Pastor Bob was given an opportunity to learn something about brain function. In his desperation, he soaked up the information and applied it to the dilemma he was facing in his parish. He opted for a practical, whole-brain solution and this is what he said: “I’ll leave the pulpit just where it is. That will honor the preference of the left brainers. And, sometimes I’ll walk around and preach in front of the pulpit. Maybe I’ll even move right down into the aisle several times in the same sermon. That will give the Envisioners some variety and meets my need for a harmonizing connection plus it will give the Prioritizers and Maintainers an opportunity to practice adjusting to a bit of change.” Not every one in the congregation is comfortable with all aspects of Pastor’s Bob’s solution but the atmosphere has lightened considerably.

Prayer has been studied for eons but perhaps more scientifically in the last couple of decades. Hundreds of studies show the benefit of prayer to plants and humans; to the individuals who do the praying, and to those who are prayed for whether or not they know about the prayers. Perhaps even more than other types of activities associated with religion, spirituality, and worship, prayer is intensely personal. The different-strokes-for-different-folks framework is essential when discussing prayer (see Table 8).

Even the way in which an individual approaches prayer (a form of meditation) can be impacted by his/her innate giftedness and can differ based on brain lead, sensory preference, and extraversion/introversion. For example:

Table 8. Approach to Prayer (a form of meditation)

Prioritizing Division

Extrovert: May pray for the purpose of demonstrating to others how it is to be done Introvert: May engage in prayerful activities (e.g., research on prayer, archeology research, read quota of selected religious writings, meditate on an element of theology or doctrine) | Envisioning Division

Extrovert: May pray with religious writings as metaphor (e.g., Bible, Koran) or may take a pilgrimage/climb the Himalayas with a guru Introvert: May engage in prayerful activities (e.g., walk by the ocean, meditate in nature, hike in the mountains, ponder ideas or philosophies). May write creative prayer |

Maintaining Division

Extrovert: May pray during scheduled or habitual prayer routines following specific guidelines (e.g., prayer wheels, prayer beads, formula formal, burning candles) Introvert: May engage in prayerful activities (e.g., silence, walking alone in the garden, copying written prayers, reciting prayers, reciting memorized scripture) | Harmonizing DIvision

Extrovert: May pray in communal or sharing situations (e.g., coffee hour, reading/prayer group) that includes expression of emotions, singing, touch, and intense spiritual experiences Introvert: May engage in closet prayer (e.g., alone, religious orders, walking, gardening), tries to discover how other individuals or cultures expressed a prayer life |

Recently researchers identified a small group of cells in the right temporal lobe of the cerebrum. These cells are believed to help individuals give meaning to spiritual experiences. In fact, a cordon within the Corpus Callosum has been discovered that connects the left and right temporal lobes. In a practical sense, this helps to explain why participation (as opposed to observation only) may result in a more whole-brained experience.

For example, picture a worshipper who remains in the pew and observes the ceremony versus one who gets up from the pew, walks up to the alter, and actively partakes of the bounded shapes in holy communion. In the first instance, the individual certainly might ascribe meaning to the witnessed experience and pick up insight from observing the gestures and listening to the tonals (from the basal right). The individual who actually participants, however, and handles the bounded shapes (from the basal left) will likely have a more global and/or enhanced experience because of the connection between the basal left and the basal right.

Consequently, there may be something to be said for developing sacred rituals that appeal to all four thinking styles, or adapting the rituals in such as way that each individual can be comfortable actually participating and processing the experience for greater meaning.

As a cerebral function, research places humor primarily in the Envisioning division although engaging the whole brain may certainly enhance one’s humorous appreciation of specific situations. Laughter, on the other hand is a sound, and is believed to be generated in Broca’s Area as with audible speech (in the Prioritizing division).

In general, individuals are socialized to take religion quite seriously. This often means that humor and/or laughter in relation to religion or worship activities is discouraged. This is regretful because tasteful and appropriate humor (although, again, the different strokes for different folks definitely applies here) can increase the likelihood of information being transferred into long term memory for recall at a later date. Here are a few memories of a Envisioning PK and the humorous situations that made it extremely difficult to contain one’s laughter!

I was a card-carrying member of a select group collectively known as Preacher’s Kids or PKs for short. No one really knows what’s is like to be a PK unless he/she has been there and done that, to use today’s vernacular. There were some positive things about growing up in a clerical household and, as with everything else, some not-so-positive things. I’ve often said that it was the worst experience of my life and the best. I tend to laugh about some of the not-so-positive experiences the farther removed from them I become in adulthood. Certainly, some of them were humorous, although that perspective often seemed to get lost in the embarrassment or expectations for propriety in which many of the adults appeared to be immersed.

My only partially stifled giggles usually bubbled up in the most undesirable (to some people’s way of thinking) of situations. At funerals, during excessively long sermons, in the middle of stern lectures from the teacher, even during prayer. A very elderly gentleman, who fell asleep during one especially long supplication, began to snore loudly. Gradually he slid down, down, down in the pew until he plopped onto the carpet. Splat! The jar woke him up. “Oh for Pete’s sake!” he blurted out disgustedly. I’d meant to keep my eyes closed as I’d been instructed 75,000 times. But the prayer was so long and in a search for variety I’d just opened one eye a tiny slit. Consequently, I saw the whole incident and found it absolutely hysterical. Mother elbowed me in the ribs and hissed, “Stop it!” Of course, the harder I tried to control my mirth, the more it insisted on trying to burst forth.

And there was the time I attended a funeral with my father. Mother was home sick with a headache (she absolutely hated funerals) and someone had to represent the family. That someone was me. I did quite well until the end of the service when we all filed past the casket. As I looked at the woman lying there so still with a wilted rose in her hands, I noticed that one of her dangle earrings had gotten twisted. The end of it was actually sticking into her ear canal. I burst into laughter at the incongruity and debated whether or not to pull it out or leave it alone. The woman behind me hissed that I was to move along which solved my dilemma.

On the way home, however, my father had another of his little talks with me. They always began with, “What was it this time?” I explained about the earring. While a tiny twinkle in his eye told me he might be appreciating a portion of the story, he rather severely reminded me that the mourners would undoubtedly not have found anything funny about the incident and I needed to have concern for their feelings. (In retrospect, I believe my father had a bent in the Envisioning division. However he operated much of the time from the Harmonizing and Maintaining division. I loved my Dad and wanted to please him but life was just so funny! It was perhaps that sense of humor that kept me alive during some of the darker valleys I would travel later in my life

There were other incidents during which I tried to contain myself with only marginal success. There was a teacher who meant to tell me to finish my spelling. He actually admonished in no uncertain tones, “Sinish your felling” and then refused to share my sense of humor in that situation. Neither did the usher who lost his toupee while bending over to pick up a dollar bill that had slipped off the offering plate. I scrambled to retrieve it for him and my efforts were only partially successful because, in the process, I managed to knock the offering plate from his hand as I tried to give him back his hair. After that service, a very conscientious church member asked me ponderously if I didn’t find it hugely significant that there were no pictures of Christ smiling. Not just in church but anywhere. I did! Find it hugely significant, that is. I figured it was because all the paintings had been done by adults who had lost any sense of humor. That time I did manage to bite my tongue before I offered my considered explanation, however. There have been other times when I was less restrained.

I certainly was more empathetic than some might have been when, years later, a Bible-class student was caught red-handed, in the act, of trying to transplant a frog into the girl’s rest room. The pug-nosed, freckled-faced thirteen-year-old had draped himself dejectedly across one of the wooden chairs, had run his hands through unruly auburn hair and queried; “Do you think God has a sense of humor? My teacher sure doesn’t!” Struggling not to laugh (one was supposed to uphold respect and authority and whatever else), I chose to begin by addressing the difference between possessing a sense of humor and choosing to apply it to a particular situation; his most recent prank, for instance. He had grinned somewhat ruefully and persisted, “But does He?” “Absolutely,” I said with certainty. “Research has associated the function of humor with the Envisioning division and I believe God had something to do with the design of the human brain. It stands to reason the Deity must have a sense of humor, since it was important enough to be included in the design.” Then the student wanted to know why the teacher was missing that part of the brain. And so it went . . .

In the Book of Philippians, the Apostle Paul offers some helpful advice. He wrote,make my joy complete by being like minded. Having the same love, being one in spirit and one in purpose. He did not admonish human beings to be clones of each other (even if that were possible) but rather encouraged his congregations to be one in spirit and purpose. Each individual’s unique giftedness makes a contribution to the whole. By welcoming those differences even in worship, individuals can open the door to wholeness in their own lives.

To travel the path of personal and spiritual growth, to introduce oneself and others to healthier and more desirable patterns of behavior, is a challenge. It requires the taking of a risk. Understanding one’s own individual preferences can enable one to maximize their own giftedness while, at the same time, honoring the giftedness of others. This process can encourage individuals to contribute from their own position of preference and collaborate with others who have strengths where they have weaknesses. Above all human beings can avoid wasting valuable energy in capricious and meaningless controversy, much of which simply derives from differences. On this journey, example is often the best teacher and whole brain strategies, the best long-term solution.

The Only Constant in Life is Change—How to Deal with It More Effectively

In 500 B.C., Heraclitus reportedly said, “Nothing endures but change.” Some deal with change more effectively than others and part of that likely relates to a specific brain’s innate energy advantage or brain lead. Research by Dr. Richard Haier, of Southern California, has shown that the brain expends less energy when completing tasks that use functions within its biochemical preference. That may be one reason why you tend to procrastinate and drag your feet when facing a task that requires higher expenditures of brain energy. And yes, your energy advantage will likely impact the way you approach change.

Initiating or participating in change is likely to be more successful when you understand that your approach to change will likely reflect your own innate preferences including your brain bent. You are not locked into responding (or reacting) based on your innate preferences, but when you know what those are it can help you to make a different choice by design when that would be more likely to result in a positive outcome.

A young man, I’ll call him Bob, accepted a call to administer a fairly large church. Bob told me his story when he attended one of my brain seminars. It so happened that the pulpit in his new church was immense, dominating the platform. Being rather short of stature, Bob not only felt dwarfed by the pulpit but totally separated from the congregation. One day, with the help of a couple of deacons, he moved the imposing pulpit to one side of the platform. At the next service he was unprepared for the storm of protest that ensued. Not understanding much about the human brain, at that time, Bob was unsure of the best course to take, “If there is a best course,” as he put it.

We had just spend an hour talking about the brain function and energy. Here’s a short summary: The cerebrum, the largest portion of the human brain, is composed of eight lobes. These are divided by a natural fissure into the left and right hemispheres. In turn, each hemisphere is divided by another natural fissure, resulting in four divisions. Each possesses its own style of thinking.

Although there may be some overlap, each cerebral section is believed to be responsible for leading different functions. For example, the Prioritizing division enables you to set goals and to make decisions. The three left posterior lobes or Maintaining division help you to follow routines accurately and maintain the status quo. The three right posterior lobes or Harmonizing division help you to create harmony and provide meaning to spiritual experiences. And, yes, the right frontal lobe or Envisioning division helps you adapt (change!). In other words, how you think—and whether you relish change or resist it—likely has its roots in your own personal biochemistry.

Review the following mini-descriptions of the four cerebral divisions. You will likely identify more strongly with one or two of them based on your own brain bent.

Prioritizing Division (Left Frontal Lobe) Tend to:

| Envisioning Division (Right Frontal Lobe) Tend to:

|

Maintaining Division (Left Posterior Lobes) Tend to:

| Harmonizing Division (Right Posterior Lobes) Tend to:

|

Simply because you may have an innate tendency to approach change from one of these perspectives, however, does not limit you to that perspective. The four divisions were designed to work together. Consequently, you can choose the way in which you will ultimately respond in any given situation. Furthermore, to a large degree you also choose how much or how little distress you will experience in the process. For example, when you understand that four different brain bents exist, you can learn to avoid some of the foolish controversies and ridiculous arguments often observed on this planet.

Back to Bob’s story. He unwittingly found himself in the middle of one of those controversies. He had become accustomed to delivering his sermons as close to his congregation as possible. Wearing a lavelier, he sometimes left the platform and walked right down among the people. He genuinely wanted to nurture and encourage his flock.

Let’s analyze the complaints:

A church board meeting was called. After three hours of heated discussion, the don’t move the pulpit contingent prevailed. The following week Pastor Bob arrived at church to find the pulpit in its original position and attached firmly to the platform!

Knowing that he really enjoyed preaching eye-to-eye, I asked Bob how he planned to solve this dilemma. “I’ll leave the pulpit just where it is,” he said. “That will honor the perspective of the Maintaining divisioners. But I’ll preach in front of the pulpit some of the time during each service,” he added thoughtfully. “That will give the Envisioning division some variety, meet my own Harmonizing division brain-bent preference for connection and, (there was a twinkle in his eye) give both the Prioritizing divisioners and the Maintaining divisioners a chance to practice adjusting to change.”

Mark Twain would have enjoyed Bob’s solution, I think. Twain’s philosophy was that it isn’t best for all to think alike. Indeed, it is difference of opinion that has created the stimulus for many great and useful inventions.

This was also true in antient biblical times. A difference of opinion resulted in simplifying the multitudinous rules set out for the Gentile believers, as well as the creation of a second missionary team (Acts 15). Human beings differ so widely in disposition, habits, education, that their ways of looking at things vary. Using current brain terminology, you could say that each person’s brain bent significantly contributes to this diversity. Indeed, much of the controversy in homes, schools, churches, and work environments results from a lack of understanding that it is helpful for persons of varied temperament to associate together and that harmonious blending is not only desirable but actually possible.

Change is life! Therefore, the question is not, “Will you change,” but rather, “How will you approach the change?” Will you turn a deaf ear or smile politely and say, “Maybe someday?” Will you move toward change only half-heartedly and temporarily? Will you review your options and embrace change consistently when it is of benefit?

To travel the path of personal and spiritual growth, to introduce yourself to healthier and more desirable patterns of behavior, is a challenge. You have to take some risks. Understanding your own individual approach to change can enable you to avoid procrastination on one hand and capricious whim on the other. Approaching change from your own brain bent, and accessing functions from other divisions of your brain as needed, can help you to be more successful overall. When change is necessary or beneficial, remember that example is the best teacher and whole brain strategies are the most effective.

Prioritizing Division Left Frontal Lobe

| Envisioning Division Right Frontal Lobe

|

Maintaining Division Left Posterior Lobes

|

Harmonizing Division Right Posterior Lobes

|

“We won!” exclaimed Josh, sliding into his chair at the dinner table. “Seven games in a row. I love playing Aussie Rules!”

“You love winning,” said his brother, Ned. “Me? I’m not into competition.”

“I like women’s footy, especially when we ditch keeping score and just have fun figuring out new plays,” said Janet.

“What’s the point of playing if you don’t keep score?” asked Josh. No one answered.

“Four siblings and we’re all so different,” said Gina, Janet’s twin.

“Some brains like competition, others don’t. Some like to play, others prefer to watch,” said their father, helping himself to more mashed potatoes and gravy. “I played footy from the time I could chase a ball. My brother, on the other hand, not so much. Your Uncle Perry would rather work with leather than chase it. Probably the reason he now makes footy gear. And he’s very good at what he does.”

“No chasing leather for me,” said Ned.

“I must have inherited your competitive genes, Dad,” said Josh.

“That, and perhaps cellular memories (epigenetics) from your father’s years of playing,” said their mother. “He had twenty years of footy under his belt before we met, married—and made you.” They all chuckled companionably.

“What makes a person love competition?” asked Gina. “I like to win when we play games during physical education, but never so badly that I try to break the rules or cheat like some do. That makes me very uncomfortable.”

“The love of competition likely has multiple underpinnings,” said their father. “Genetics, epigenetics, opportunities and expectations, perceived rewards, encouragement from family and mentors—and certainly, individual brain differences. For example, an extroverted brain like yours, Josh, thrives on the stimulation competition offers. An energy advantage in the left frontal lobe or prioritizing division of the cerebrum contributes, too, as that part of the brain wants to win. Ned’s brain, on the other hand, leans toward introversion, preferring less stimulation in its environment. His energy advantage is more likely linked with the harmonizing division, concerned with connection, empathy, and helping others.”

“But I’m happy to cheer in the bleachers,” said Ned. “I can actually get quite pumped at times—as long as I’m off the field.” He laughed.

“The testosterone effect,” said their mother. “In addition to surges related to developmental periods, testosterone secretion increases in the presence of any form of competition, including active participation in a competitive situation or virtual participation through observation. Assertive-aggressive behaviors tend to escalate in both genders as testosterone levels rise—although the relative rise appears to be more dramatic in males than in the females. Dr. Michael Gurian points out that although testosterone levels go up with competition in both males and females, males have a much higher testosterone baseline, which makes males on average more aggressively competitive than females.[1] The relationship between testosterone and assertiveness is more complex in females according to Dr. Helen Fisher. Levels of testosterone in females do not appear to rise and fall based on wins or loses in sports as levels do in males.”[2]

“The desire for sex arises in the hypothalamus, stimulated by hormones, especially testosterone,” said their father. “And males have 10-20 times more testosterone.[3] Competition raises testosterone levels, rivalry fuels aggression.[4] Since testosterone tends to increase in the presence of competition, dating directly after an exciting competition (e.g., football game, track and field competition) can be a risky affair. In fact, the testosterone phenomenon may play a factor in date rape.”

“I’ll remember that,” said Janet.

“We best all remember that,” said Ned, nodding

“The thrill of competition can increase adrenaline levels in a person’s body, too,” said their father. “As adrenaline levels rise, so does dopamine, the feel-better chemical. Some individuals pursue competition because they are addicted to their own adrenalin and dopamine, released in the presence of competition. That underscores the importance of balance in life. Even a good thing taken to the extreme can result in negative outcomes.”

“So what about our brains?” asked Janet. “Gina’s and mine?”

“My guess is that your brains are probably ambiverted,” said their father, “although there will be differences since every brain on this planet is unique. No two brains are exactly the same and each person’s brain operates most efficiently when involved in activities it does best.[5] You girls each enjoy some stimulation followed by some quiet recovery time. You can compete but don’t particularly gravitate toward it. Janet, your brain’s giftedness may align with the envisioning division that likes innovation, variety, and figuring how to do things in a new way. Gina, your brain may function most energy-efficiently from the maintaining, division because you learn the rules of the game quickly and seem to keep score easily.”

“Is competition good or bad for the brain?” asked Ned.

“Healthy, balanced competition can stimulate brain function and add spice to life,” said their mother. “Taken to the extreme, it can turn everything into a win-lose and sabotage relationships.”

“I know,” said Josh. “Gary practices hard to hone his skills but if the team loses—his dad loses it, too. He berates his son or another player for making mistakes or makes nasty remarks. I feel sorry for Gary.”

“Poor sportsmanship,” said their father. “Learning to reward yourself for doing your very best and yet knowing how to be happy for the winner—even when it isn’t you—are important life lessons.”

“Historically, a male’s sense of self-worth often has come from arenas of combat, where he has struggled on the job ladder, competed in sports, vied in entertainment or fought in politics,” their mother explained. “When cooperating becomes more desirable than competing, some males may perceive their main source of esteem—competition—is undermined. While some female brains like competition, women have generally competed more for male attention than in areas of sports or entertainment. And speaking of brains,” their mother added, smiling, “while all four of you have unique brains, each of you—repeat, each of you—carries their dirty dishes into the kitchen.” They all laughed and began stacking plates.

Different strokes for different folks. Fortunate indeed are those who come from a family system that recognizes, honors, and embraces individual uniqueness, helping each person to hone their brain’s innate giftedness—and thrive.

1 Gurian, Michael, PhD, and et al. Boys and Girls Learn Differently!

2 Fisher, Helen, PhD. The First Sex.

3 Pease, Barbara and Allan. Why Men Don’t Listen and Women Can’t Read Maps.

4 Moir, Anne, and David Jessel. Brain Sex, the Real Difference Between Men & Women.

5 Restak, Richard, MD. Mozart’s Brain and the Fighter Pilot.

Arms on the table, head in his hands, he sat alone. The other participants had already left the lecture hall. It was the noon break and I was hungry. Ravenous, actually. Something about the way his body language shouted pain, however, held me back from making my way to the dining room.

Walking over to his table, I perched on the edge. “Is there anything you need from me?” I asked quietly.

His head shot up. Eyes blazing, fists half clenched, face red, hair standing on end, and voice rasping, he almost spat out the words. “You said brain-function information could help answer questions and all your class has done so far is to create more of them!”

“What’s the question?” I asked, trying to keep my face neutral and a chuckle repressed. He looked so much like an angry little boy dressed up in adult clothing.

“Question?” he thundered. “You mean questions! Why did I always feel different growing up? Why was I pushed into the family business? What has zapped my energy? Why are all my relationships short-term? Why am I so miserable? How come I’m even here? He closed his eyes and his head fell back into his hands.

“When I was a little girl, in the late 1800’s,” I began, trying to lighten the situation with just a tad of humor, “one of our . . .” but he cut me off.

“I’m not the least bit interested in when you were a little girl!” His frustration bit into the air. “I’m interested in answers to my questions!” At least he feels safe enough here to reveal how he’s really feeling, I thought to myself.

I remained silent long enough for him to once again raise his head. We stared at each other for a while. “Right,” he said finally. “It’s your turn. So speak.” This time I did chuckle.

“First of all, the brain cannot really answer ‘why’ questions. It can only provide it’s opinion and no doubt your brain has some opinions about the ‘why’ questions you have.” He remained silent but nodded his head almost imperceptably. I continued. “One of our neighbors was always saying there’s more than one way to skin a cat. In fact, I heard that phrase so often it must have burned itself into my long-term memory. Decades later, I heard myself throw out that same line during a stimulating but rather tense discussion with a group of colleagues. Without so much as a pause, one of the brain researchers retorted, ‘if you have a cat to be skinned.’ At the time I was startled at that unexpected response. It was only in retrospect that I understood its value.” The man’s eyebrows rose slightly. I continued.

“Brain-function information, along with serious family-of-origin work, can help you discover answers to your questions, questions you may have had for decades. But you need to ask the right questions. In the case of the proverbial cat, the appropriate question may not be how do I skin a cat, or even which method do I use, but is this a cat and, if so, does it need to be skinned?”

“So you have the nerve to sit there and tell me I’m asking the wrong questions?” His voice demanded but one of his eyes contained the glimmer of a twinkle.

“Not wrong questions,” I replied, “but questions that might be more manageable if they were rephrased.”

“Such as,” he demanded. This time the twinkle was more pronounced.

“These are some of the questions I’ve asked myself over the years and brain-function information definitely helped me to answer them:

He unwound his lankiness from the chair and ran his fingers through his hair. There was actually a hint of a smile on his face. “Let’s get lunch,” he said, grabbing pencil and paper, “and start jotting down some rephrased questions.”

“Deal,” I replied, “as long as you remember that your quest involves a process more than a defined destination.” Already moving toward the door, his laughter echoed around the lecture hall.

All progress begins with a new question. Sometimes we delay our journey because we’re asking unhelpful questions, or we waste time and energy on questions that don’t really matter all that much. As Ellen Goudge put it, To seek empowering answers you must know which questions to ask.

Ah, yes. “Is this a cat and, if so, does it need to be skinned?”

He sat hunched over in the leather wing chair, his head in his hands. “My life was going so well,” he said, his voice taut with emotion. “Now, all of a sudden everything seems to be going to hell in a hand basket.” He groaned. “I thought I had the tools to live more successfully but I can’t seem to locate them right now.” His face twisted into a wry grin.

Indeed, several issues had surfaced in his life; issues that needed to be dealt with in order for him to move forward. Not surprisingly, in trying to deal with those issues he had reverted to some old, familiar patterns of behaviors. Since they hadn’t been very effective in the past, however, there was every reason to believe they wouldn’t help to keep him centered on his personal growth journey in the present. Indeed, making the transition from repeating old patterns of behavior to implementing more functional ones can resemble the proverbial two steps forward and one step back. It’s all about making choices and consistently practicing new strategies.

“Unfinished business,” I mused aloud. “It can be overwhelming, especially if you attempt to deal with everything at once rather than breaking things down into manageable bite-sized chunks.”

“My unfinished business is littered with expectations,” he continued. “Some of them are my own, based on the way in which I was brought up and my life experiences, and some are being heaped upon me by others.”

“Let’s take one of the relationship issues with which you’re currently struggling,” I suggested. “In order to be genuinely successful you must first be true to yourself. That’s the only way in which you can identify the relationships you want to take with you on your journey and be true to them. In a practical sense, all that means is that you take one small step every day toward who you are. In my own experience I’ve found that sometimes I’ve circled around my path trying to find it. However, as I consciously identify and acknowledge who I am and move toward embracing and developing my innate giftedness, one step leads to another. That formula can work for all of us. Before we know it, we have found our own unique path.”

“But what I think I want for the rest of my life doesn’t match what I thought I wanted in the past, what others think I should want, or what they want from me now.” He sighed and the sound was deep and painful.

“I read one of those elevator quotes the other day. There was no source listed but I was impressed enough to write it down.” I pulled a card from my wallet and read:

“We need always to hold onto our dreams; to never give them up simply because they might inconvenience others. To do otherwise means that we might arrive at life’s end with empty hands. We can only hold in our hands our innate giftedness. If we have never become the person we were intended to be, if we have not developed and embraced our giftedness, we have nothing in our hands.”

He nodded. “But the tools,” he persisted.

“Right there in your hands, along with your innate giftedness and your dreams,” I responded.

“Do you recall the ancient story about Moses?” I ventured. “The one where Moses was asked, ‘What’s in your hand?’”

“Matter of fact, I do,” the young man replied. “I learned it in Hebrew school.”

“And what did Moses answer?” I asked.

“A staff,” said the young man. “Just a staff.”

“Metaphorically, the staff represented his innate giftedness,” I said. “And with that staff Moses led a multitude from Egypt in one of the most amazing migrations in history.”

A smile tugged at the corner of his mouth. He looked down at his hands; large, powerful, capable. “Well, what do you know?” he said, his eyes twinkling. “My giftedness, my path, my dreams, and the tools are right here in my hands. And I know what they are. “

I watched him stand up, take a deep breath, straighten his broad shoulders, and metaphorically get back on his path—giftedness, dreams, and tools in hand.

The good news, I thought to myself, is that as we embrace the process, in addition to reparenting ourselves, we eventually become strong enough to be our own therapist. We access our support systems and resources quickly and effectively. We consistently make more functional choices.

What’s in your hand?

In his book, Maybe (Maybe not), author Robert Fulghum relates a tale from the world of chess. During an international competition years ago, so the story goes, Frank Marshall was evenly matched with a Russian master player. In a crucial game, Marshall’s queen came under serious attack. His opponent, as well as the spectators, assumed that Marshall would follow conventional rules of chess and move the queen—the most important offensive chess piece—to safety.

He didn’t.

At the end of the time allotted for deliberation, Marshall picked up his queen and intentionally placed it on the most illogical square of all, a position vulnerable to capture by at least three other pieces. Marshall had done the unthinkable. He had sacrificed the queen!

There was a collective gasp from the dismayed spectators. Calmly, Marshall surveyed the board, seemingly immune to the murmurs of the usually silent crowd. Murmurs such as: Bizarre! Can’t believe he did that! He’s got to be nuts. No one in his right mind would do such a thing!

His opponent was initially puzzled. And then it began to dawn on the Russian, as well as on the spectators, that Marshall had made what has often been referred to since as the most beautiful chess move of all time. Regardless of how the queen was captured, Marshall’s opponent would eventually lose. Seeing that eventuality, the opposing player conceded the game.

By suspending conventional thinking, by being willing to consider an option outside of traditional expectations, Marshall had become the ultimate winner.

We all grow up learning certain societal expectations. Some of them are helpful. Many are not, especially when they run counter to the way in which our own brains work most efficiently.

In life, we sometimes glimpse a personal vision that requires us to think outside the confines of conventionality; a vision that requires us to take an imaginative risk. Actually necessitates this, if we are to honor our own innate giftedness and live the personhood we were intended to embrace.

Some find it too frightening to go against convention. The murmurs of society crush them into confusion, discouragement, depression, and even immobility. Thus, they lose the opportunity to serve from the basis of their own innate giftedness.

A few study the board of life, consider the options and choose (often to the consternation of those around them), to cross the line of societal convention. They elect to metaphorically sacrifice the queen for their own long-term good and, interestingly enough, often for the long-term benefit of society, as well.

How is it in your life? Evaluate who you are, your options, and the consequences of each. Select a course of action that matches your innate giftedness. Be willing to sacrifice the queen, if necessary, to follow your vision.

It’s your move!

You cannot control what happens to you, but you can control your attitude toward what happens to you, and in that, you will be mastering change rather than allowing it to master you. —Brian Tracy

We were moving again! Barrels and boxes had been hauled up from the basement and trunks carried down from the attic. My brother and I were expected to pitch in and sort and pack. Some of it was fun, some pure drudgery. I was amazed that so many people expressed sympathy toward us for having to move. We took it absolutely for granted, a periodic occurrence in the lives of preacher’s kid. In the main we viewed it as another adventure and, although we didn’t realize it at the time, it provided plenty of opportunity to practice the art of graceful change.

As I grew older, I realized that many people did not perceive change as an adventure or as an opportunity. They were more comfortable with the known and seemed to forget that, almost without exception, the known was once the unknown.

Recently I was asked to address this topic with a community group of young adults. One individual suggested that change was undesirable and that we should strive, even stubbornly, to maintain the status quo. Another believed that while change was necessary at times, it should be orchestrated carefully by “someone in charge.” Still another thought that change was the spice of life and one couldn’t have enough of it. A fourth added that change wasn’t really the issue; but rather whether or not everyone was comfortable with the change. All these views were expressed with great intensity, and discussion was lively.

I pointed out that because every brain on the planet is as unique as the owner’s thumbprint, every individual would tend to approach change somewhat differently, although a general blueprint of four distinctly different approaches can be helpful.

Understanding your own individual approach to change does not limit you to that perspective. It can enable you to avoid procrastination on one hand and capricious whim on the other. You may be responding from your brain’s innate energy advantage or you may be reacting based on learned skills related to change. The good news is that you may select any number of brain functions to help you respond to or initiate change successfully. (You may refer to some of the information we discussed in the Addendum that follows.)

You have the ability to select the way in which you will ultimately respond in any given situation. Furthermore, to a large degree you also choose how much or how little distress you will experience in the process. Developing an increased awareness of how your brain approaches change can give you a huge advantage. It can enable you to select a more appropriate response to change based on the situation and on the outcome you would like to achieve. It can help you to implement the 20:80 Rule in a timely manner, especially when your brain did not initiate the change.

The 20:80 Rule is based on comments attributed to Epictetus, a 2nd-century philosopher. He reportedly believed that an individual was ultimately impacted less by a given event and more by what the individual thought about the event. To paraphrase in 21st-century terminology, only 20% of the effect to one’s brain and body is due to the event. About 80% reflects what the person thinks about the event, the importance he/she places upon it, and the actions taken in relation to it.

Mark Twain’s philosophy was that it is good for people to think differently. Indeed, it is difference of opinion that has created the stimulus for many great and useful inventions. Human beings differ widely in disposition, habits, education, and style of perceiving information. Each person’s brain lead significantly contributes to this diversity. Much of the controversy in homes, schools, churches, and work environments results from not realizing that it is helpful for persons of varied temperament to associate together, and that the outcome of collective wisdom is usually greater than that of one brain only. When you understand—and internalize—that no two brains on this planet are identical in structure, function, and perception, you can often prevent or sidestep foolish controversies and meaningless arguments! Harmonious blending at a workable level is not only desirable—but also possible.

At the break, perhaps on purpose, perhaps subconsciously, someone started humming a tune from the movie Mary Poppins. Remember the line “Chim chiminey chim chiminey chim chim cher-ee?” ”Those words are fanciful and signify something that primarily exists only in one’s imagination. However, Webster’s Dictionary includes “visionary” as one of the definitions of the word chimerical. I like that. In fact, it suggested the title for this article. Each one of us can be visionary about the way in which we approach change.

As Heraclites supposedly commented in 500 B.C., “Nothing endures but change.” Change is life! The only constant in life is change. Therefore, the question is not, “Will you change,” but rather, “How will you approach the change?” Will you turn a deaf ear or smile politely and say, “Maybe someday?” Will you move toward change only half-heartedly and temporarily? Will you grudgingly accept change only when it is forced upon you? Or will you take charge, and orchestrate the change—especially when it is inevitable or to your benefit?

Recently I saw a sign posted in a hospital elevator that said: People change when they hurt enough that they have to, learn enough that they want to, or receive enough that they are able to. Many people think of change primarily in terms of what happens to them. I like to think of change in terms of what I can make happen positively for myself and for others! As Tracy put it, master change, rather than allowing it to master you.

ADDENDUM

A natural fissure into the left and right hemispheres divides the cerebrum, the largest portion of the human brain. In turn, each hemisphere is divided by another natural fissure, resulting in four divisions composed of eight lobes.

Although there may be some overlap, each cerebral section is believed to possess its own style of processing information and be responsible for leading specific functions (see figure of the four cerebral divisions). How you think—and whether you relish change or resist it—has its roots in your own personal biochemistry, impacted and compounded by your own personal history and environment (e.g., the old nature/nurture equation).

For example, functions in each cerebral division are designed to assist you with the following tasks related to change:

Prioritizing Division

| Envisioning Division

|

Maintaining DIvision

| Harmonizing Division

|

Initiating or participating in change is likely to be more successful when you understand that your initial approach to change reflects your own brain’s innate advantage—a biochemical preference for processing information in one of the four cerebral divisions over the other three. Review the following mini-descriptions of the way in which each cerebral division tends to approach change. You will likely identify more strongly with one or two of them.

Prioritizing Division Tends to:

| Envisioning Division Tends to:

|

Maintaining Divisioni Tends to:

| Harmoniziaing Division Tends to:

|

It was a uniquely diverse group. Interesting and intellectually stimulating, their ages ranged from 17 to 87. There were people of European ancestry as well as those of African, East Indian, Native American, Hispanic, and Oriental backgrounds. A variety of countries were represented including Canada, United States, India, Mexico, Great Britain, Hong Kong, Africa, and Australia. All were enrolled in The Brain Program.

I had presented the concept of brain bent, a term that refers to a brain’s built-in advantage for processing information energy efficiently. Humans are each believed to possess an innate biochemical preference for paying attention to and managing data using one of four natural divisions of the cerebrum over the other three. (Refer to Table at the end.)

In the process, I had summarized a study involving primate research on pecking order. Briefly, researchers placed thirty male primates in an enclosure and left them alone for a few hours. They rank-ordered themselves from 1-30. Studies of these primates showed a correlation between lower positions in the pecking order and decreased levels of dopamine and serotonin in the brain along with increased levels of stress hormones. Self-esteem and assertiveness levels also tended to reflect pecking-order position.

Some believe that a similar situation may occur in the human brain, as well. When a person is utilizing his/her brain bent and it matches societal expectations, that person may tend to have higher circulating levels of dopamine and serotonin and exhibit higher levels of self-esteem and assertiveness and lower levels of stress hormones. Of course the reverse would also be true.

Over lunch we discussed the hypothesis that individuals whose brain function matched what their culture emphasized might find themselves higher on that country’s pecking order, versus those who did not. Using the former USSR as an example, an historian in the group explained, “The system was probably run by males with a bent in the Prioritizing division, who expected everyone else to function using skills in the Maintaining division, while those with a bent in the Envisioning division (e.g., writers, poets, composers and arrangers, inventers, and many artists) and in the Harmonizing division (e.g., dancers, musicians, and counselors) were discriminated against in terms of the types of skills that were rewarded.”

A college professor suggested that entire countries could be assigned a brain bent, at least in terms of which skills were emphasized and rewarded. It would therefore be possible to theorize some correlations. “England could be viewed as emphasizing skills in the Maintaining division,” he said. Evidence for that position was its continued adherence to centuries-old rules and specific rituals dealing with knight-hood and peerage, to say nothing of coronation protocols. It also rewarded skills in the Prioritizing division through the continued promotion of the monarchy, the nobility class system, and the global conquest that had resulted in creation of the British Empire.

“And in the earlier part of the 20th century,” said a woman with a European accent, “Germany tended to emphasize functions in the Prioritizing division.” Examples here were a goal-oriented conquest for dominance, a dictator-style government, citizenry being expected to unquestioningly fall into step, and punishment of those who couldn’t or wouldn’t meet the approved standard.

“Japan embodied an interesting split tween the Envisioning and Maintaining divisions,” offered another. “It was gifted in envisioning and mimicking what other countries had produced, especially cars and electronics—often doing it more successfully and for less cost.” But the myriad of ritualistic details surrounding the Tea Ceremony was suggested as an example of Maintaining functions.

“I think Ancient Greece emphasized double-frontal functions,” offered a participant who taught evening classes at the local Junior College. “There were innovative artistic and architectural wonders, along with debate and goal-oriented athletic competitions.”

Almost casually, and yet as if his pronouncement was not only the last word but an irrefutable fact, one of the younger participants interrupted with, “My folks say color forms the basis of all discrimination.”

One of the older participants said, “I, too, have thought of discrimination as primarily having its root in race or skin color. Now I wonder if, while that may be a strong component in some instances, discrimination actually has its roots in brain function.” There was a pause. “For instance,” he continued, “what about slavery? Was that about color or brain function?” There was a pregnant pause followed by a dozen voices offering comments.

“I’d guess that the traders who stole or purchased individuals for the purpose of being placed into slavery had a brain bent in the Prioritizing division. Some were of European ancestry but documentaries have shown that others were themselves of African ancestry. They were goal oriented—obtaining a commodity and turning it into a profit—and the stories related to conditions on the transport ship suggest there was were few skills in evidence from the Harmonizing division relate nurturing, empathy, or a concern for proper food and creature comforts.”