If you would like to submit a question or make a comment, please email Dr. Taylor at thebrain@arlenetaylor.org.

Every brain learns “differently” because every brain is different. Some brains find it difficult to learn easily in mainstream traditional schools. They may just get by or may not get by at all. My guess is that ALE students just exemplify (perhaps at a deeper level) how brains learn differently. Some young people thrive in mainstream education. Others just get by and dislike school. All students definitely “learn” but not always what parents and teachers wish they would learn. Still others can learn but do so most effectively through alternative educational opportunities.

With ALE students it’s important to give them whole brain and multi-sensory learning opportunities. That way more associations are created in the brain, which increases the likelihood of storing and retrieving the information. It takes a bit of thought to teach non-sequentially and integrate all three sensory systems in the process. However, it can be done. That style, of course, would also benefit non-ALE students.

If they can read and articulate, it can be very helpful to read to them AND have them read aloud for a few minutes in each class. That truly stimulates the whole brain and can be very helpful for learning. Have the whole class read a couple paragraphs together and have each child read a paragraph at a time aloud while the other children listen, etc.

Depending on their age, you might have them complete the Sensory Preference Assessment and talk about the sensory data that registers most quickly and intensely in each brain. You can emphasize the importance of using all three systems by design to enhance learning and to communicate more effectively, etc. Have fun with it! When an activity is fun, human beings are more likely to remember it and use the information.

Some young people openly express their frustration toward “school,” others seethe silently, still others lash out or drop out when they perceive no one is hearing them. Unfortunately, the way in which students react often results in their becoming marginalized, if not just kicked out of school on the spot. Nevertheless, their behaviors are trying to communicate something—something about how the current educational environment is not meeting their learning needs and, in fact, may be making it more difficult for them to learn.

Although research hasn’t exactly pinpointed how the brain learns, studies have shown how the brain learns best. This is at once exhilarating, because with some effort and innovation the process of learning could be enhanced significantly for most, and depressing—since millions of brains are experiencing sub-optimal learning as they move through or drop out of the educational process in a variety of environments, some of which are at least demeaning if not outright punishing or abusive at some level. Following are just two examples.

It’s no wonder some students are frustrated. Moreover with brains only partially completed, they are unable to articulate what isn’t working—they just know they’re struggling.

In this 21st century, educational systems could be capable of providing learners with brain-compatible environments and with curricula that support the way in which the brain naturally learns best. The question is, will they? For the sake of millions of brains on this planet, the answer needs to be “yes!”

Thank you for your comments. I am happy you enjoyed them. I enjoyed doing all 12 episodes. To your question, first, we don’t use commercial breaks. Second, when I brought the idea to the production team and they decided to go with it, we looked at the length of an average TV presentation between commercials and decided to aim for 5-7 minutes (although recently it seems that there are 5-7 commercials between each content segment!). Anecdotally, it appears that due to TV, video games, social media, and electronics of every hue and color, the attention span of the human brain is unfortunately diminishing. I think that’s unfortunate. Nevertheless, it is important to “meet people where they are” as much as possible. Tell your kids that Quinton Quill loves being the host. He is such a little “feathered ham.”

I’ve been presenting seminars related to brain-function for decades and much of the content came from research papers and from conversing with brain researchers. It takes years to get a book published and by then new data have emerged! Now it seems that books related to the brain are popping up all over. Often these books contain information about brain function similar to what I present in my seminars—sometimes just stated in a different way and using different terminology. Several of my books are available on Amazon.com: The Brain Has a Bent (Not a Dent). Age Proofing Your Brain. , and the 8-book Legend of the Wild series teaching Emotional Intelligence through animal allegories. I also post a weekly video available YouTube. One series is The Magic of Emotional Intelligence; the other is Taylor Brain Bytes. You can access them through my YouTube channel if you don’t want to search the Internet. Type: Arlenetaylor.org and then click on YouTube under Resources.

The key tasks required for mastering a specific subject likely draw more heavily on functions in only one or two of the four cerebral divisions (with the caveat that all brain functions likely require the use of other functions at some level). From a brain function perspective the main purpose of formal education is to develop skills throughout the brain, not just in one cerebral division. The study of differing subject matter helps us to accomplish this. Think of these skills as internal brain software programs that you can then utilize in a variety of ways throughout life.

Yes, some subjects will be easier for you and require less energy expenditure than others based on your own innate giftedness in terms of brain function. Some will appeal to you more because they are easier for your brain to accomplish and because you are personally more interested in them.

However, one of the laws of cybernetics says that the organism with the most options tends to be the most successful. Think of studying these diverse subjects in college as a way to develop more “options” that can help you to be more successful in the long term. Even if you never “use” the skills for a specific subject again per se, you may need to accomplish some other task or activity in life that draws on skills you built when you studied that subject.

Several years ago, a brain researcher told me about studies related to the use of a colored background on PowerPoint® slides. It seems that when the background is a color (unless it is a picture of nature) you increase the possibility that some of the participants may become distracted. Their brains may recall events, positive or negative, that involved the color that is used in the background. Whether this occurs at a conscious or subconscious level, their brains will be distracted. This can be especially true if any of those memories have an emotional component. Naturally, this can decrease their tendency to learn, retain, or practically apply what is being presented—since they will likely miss portions of the information.

I have a great regard for a person’s time. It is one of the most valuable gifts you can give to another person. When individuals choose to attend one of my presentations, I want to make the best use of their time. Therefore I typically use a white background, although I may use a small colored symbol or clip art to illustrate the information.

First, I applaud your boundary position of avoiding mixing business with pleasure when both of you work for the same corporation. Second, I have experienced this type of situation at least twice in my career. Unfortunately. Someone admires what you do and wants to replicate it, but possesses “gifts differing,” as the old saying goes. They then try to compete with you rather than identifying and honing their own innate talents. Yes, people can learn some skills and pick up tips by being mentored but they can only replicate the level of competence if they are innate for their brain. In the end, the person typically does not attain the level of competence required to be really successful at those “copied skills.” Misidentifying what their brain does best can cause a tendency to misperceive how they come across to others. How they evidence this misperception may be exhibited in a wide range of behaviors.

Are you acquainted with the Dunning-Kruger Syndrome for which the authors won an Ig Nobel Prize in 2000? According to Merriam Webster Dictionary, this prize, a parody of the Nobel Prize, is awarded every autumn to celebrate ten unusual or trivial achievements in scientific research. The original paper by David Dunning and Justin Kruger was titled, “Unskilled and Unaware of It,” in which they explained that this syndrome involves a false belief or cognitive bias. The miscalibration of the incompetent stems from an error about the self, whereas the miscalibration of the highly competent stems from an error about others. It appears as an internal illusion in people of low ability and an external misperception in people of high ability. Those of high-ability tend to underestimate their relative competence and presume, erroneously, that tasks which are easy for them to perform also are easy for others to perform. Those with lower levels of relative competence fail to adequately assess their level of competence, which robs them of an ability to critically analyze their own performance that leads to a significant overestimation of their own competences. This, of course, can be deadly for mentoring as well as personal relationships and may negatively impact long-term success.

Individuals with the Dunning-Kruger syndrome tend to:

Anecdotal observations have indicated that these individuals may contact others with an offer to provide specific activities or presentations (whatever they believe their skill set to be) and then get upset when repeat invitations are not forthcoming. In all fairness, an inaccurate assessment of personal competence may derive, at least in part, from the individual’s own ignorance of actual and current standards of performance for the given skill. The pattern of overestimation of one’s competence has shown up in studies of reading comprehension, the practice of medicine, operating a motor-vehicle, playing games such as chess and tennis, and so on. The good news is that improving one’s metacognitive skills has been shown to reduce self-assessment scores as the individual became better at evaluating their own limitations.

How do I deal with this? It can be a challenge, especially when I have at times mistaken a desire on the part of another individual “to get all the help and tips from me that are possible” and/or to be aligned in the public eye with someone they perceive as successful, with a genuine desire for a bona fide personal friendship. Once I get clear about that, I can be pleasant and professional while avoiding being used primarily to enhance the other person’s grasping for success. In addition, I am clear that the only person I compete with is myself, always trying to improve my own skills. After all, every brain on the planet is different so comparing my skills with those of others is a dead-end stressor, a bit like comparing apples with oranges, as the old analogy goes. My brain’s opinion is that Dunning-Kruger Syndrome may reflect a measure of personal self-esteem, which may be exhibited as low self-worth or an inordinately high level of perceived self-worth in comparison with others.

Dyscalculia is an interesting topic. It seems to involve an innate genetic or developmental origin. Estimates are that perhaps 3-6 percent of the general population has some form of Dyscalculia. Studies have also established that one in every ten or eleven children with dyscalculia also has ADHD. It has also been seen in individuals with Turner Syndrome or spina bifida.

Dyscalculia has been confused with dyslexia—even more confusing as some brains have both. It has also been confused with acalculia: mathematical disabilities due to some types of brain injury.

Dyscalculia can present as difficulty in learning or comprehending the concept of arithmetic; trouble understanding numbers and how to manipulate them; inconsistency in how to recall facts about numbers and mathematics, or frustration when trying to do calculation involving numbers. Sometimes it can present as problems with all these mathematical aspects.

When I was a school nurse and a child was struggling with math, we first asked for a history of any head injuries. Next vision and hearing assessments to rule out problems with the sensory systems. After that, we would put the child in touch with a learning specialist for some testing. The school nurse at your son’s school would likely know some sources for that. The tests I am familiar with check for several areas such as:

An ability to remember facts related to basic math and numbers

An ability to do math operations (add, subtract, divide, multiply, fractions)

An ability to do math problems in his head

An ability to understand and solve word problems involving math

You might also do an internet search for tips on how to help a child with Dyscalculia. Every brain has something for which it needs help.

Interesting question. Obviously, given that every brain is unique, each will respond slightly differently to any measure of IQ. My understanding is that Raymond Cattell identified two forms of general intelligence: fluid and crystalized. They are believed to involve separate mental and neural systems.

Of course, overall, you use both of these types of intelligences in combination. Typical IQ tests are designed to measure both fluid and crystalized intelligences. The overall score is a combination of both these measures. According to some sources, the WAIS (Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale) is designed to assess crystallized intelligence on the verbal scale and fluid intelligence on the performance scale, the overall IQ score resulting from a combination of these two scales.

Good question, and you are correct that there are “multiple” forms of intelligence. Howard Gardner in his book Frames of Mind: the Theory of Multiple Intelligences, lists nine (9) ways in which to be “smart.” Those are in alphabetical order:

It would be quite an undertaking to attempt to devise accurate and consistently verifiable assessments for these types of intelligences. It would likely be unhelpful if there were measures for everything because every brain is different. Certainly the Johnson-O’Connor Research Foundation has attempted to devise ways to assess aptitudes since 1922.

And you are correct that many think the Intelligence Quotient (IQ) tests have been touted as assessing perhaps more than it is possible to assess, especially since one must have quite a good grasp of written language to answer the questions. My favorite IQ test is the one given by MENSA International because rather than assigning a number—which can be problematic when trying to do comparisons—they groups scores in a percentile rating.

More recently researchers such as Dalip Singh, PhD, D. Litt., of India are endeavoring to create a measuring system for one’s level of Emotional Intelligence. You can learn something from almost any assessment as long as you understand what it is designed to measure. In the end, however, getting to know yourself—including what tasks your brain does most energy-efficiently and how to use emotions and feelings to guide intelligent and appropriate behaviors—can be critical and life-changing.

It all depends on what you mean by “it wasn’t needed.” Studies in school are designed to build skills and neuron highways throughout the brain. And, yes, it is possible to do that in ways other than going to college. My brain’s opinion is that having a piece of paper stating you were able to complete a specific level of formal education can open doors that otherwise might remain closed to you (especially during a recession). The piece of paper (i.e., degree) doesn’t guarantee that you’ll be hired or retained if you are hired, but sometimes it allows you to get your foot in the door….

Do I know how many languages and dialects exist? No, I do not. I’m not sure anyone does. According to www.ethnologue.com, there are 7,117 languages spoken today on Planet Earth. Who knows how many dialects?

As for the first question, I have both spoken and written about that. Studies have shown that a newborn can immediately distinguish the language the mother spoke during pregnancy. For parents who want to give their child(ren) the gift of becoming multilingual it is best to begin early. The newborn can start recognizing the sounds for up to three languages simultaneously—more easily if a different person consistently speaks each language.

After year one, however, the baby’s brain no longer responds to phonetic elements peculiar to non-native languages. After age eight, the ability to fluently learn a non-native language gradually declines no matter the extent of practice or exposure. If possible, teach your child(ren) or grandchild(ren) a second or third language. Studies suggest that people who are at least bilingual may have a longer lifespan, likely due to the brain stimulation that results from speaking more than one language.

Very young human infants can perceive and discriminate between differences in all human speech sounds and are not innately biased towards the phonemes characteristic of any particular language. However, this universal appreciation does not persist.―www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK11007/

Two little brain organs, the hippocampi, are located in the subconscious mammalian or 2nd brain layer. One on each side of the brain. During sleep, if you get enough for your brain, each hippocampus is busy moving information that you learned while you were awake, from short-term to long-term memory in a process known as consolidation. These organs also make decisions about what to transfer based on what they think if important to you, and what you are interested in. The hippocampi also function as search engines. When you want to recall something, they will start searching your long-term memory banks, much as you search the Internet, trying to retrieve what you want.

Thank you for sharing this success story. You only know what you know, and the only brain you know is your own, filled with its own beliefs. According to some studies, many people operate from ideas and beliefs they absorbed by the age of five, often subconsciously. For example, when I was a little girl I was told in history class that Galileo ran afoul of the local religious establishment because he believed the world was round, not flat. That little ‘fact’ lodged in my brain for a long time. It turns out that Galileo did run afoul but for a different reason: he proposed that the earth revolved around the sun and that ran contrary to the belief system of the day. In 1992, after a 13-year investigation initiated by Pope John Paul II, the church finally acknowledged it had persecuted Galileo unfairly as science had revealed that the earth indeed rotated around the sun.

Sometimes emerging researched conclusions run contrary to what an individual has believed or assumed. When practically applied, however, brain-function information does work, sometimes amazingly well. Most people have little concept of how they could cooperate with their brain and minds (yes, they are separate entities) to be more successful. There is now some consensus that the mind emerges from the brain at some period during in gestation. As the minds mature (there are three of them: conscious, subconscious, and unconscious), they appear to be able to influence each other and the brain. In fact, the conscious mind can tell the brain what to do even though the brain created it. Amazing. This makes human beings different from any other type of brain on Planet Earth. One of the best metaphors I’ve heard compares this phenomenon to traffic. Vehicles create traffic. In turn, traffic can constrain and impede movement of the vehicles. I believe it is important to be open to new information, although it may run contrary to what one was actually taught. That’s what is so exciting about brain-function research! When I encounter something that runs contrary to what I originally learned in school, I search for several sources that agree with the new researched conclusions.

You’re right. It isn’t fair. Your home belongs equally to both of you even though your contribution has been caring for it and the family while your husband’s has been that of bread winner. No, life isn’t fair! But that doesn’t mean you can’t embrace it and be thrivingly successful. His comments likely derive from fear and from a sense that he may be losing control over you. Perhaps his education has been used to bolster his own sense of self-esteem and it may be extremely threatening for him to perceive that you may learn what he knows. After all, how could he then feel superior? Avoid making the assumption that his use of the word lesbian has anything to do with sexual preference. Recently someone sent me a powerful quote by Suzanne Pharr:

“How many of us have heard battered women’s stories about their abusers calling them lesbians or labeling the battered women’s shelter a lesbian place? The abuser is not so much labeling her a lesbian as he is warning her that she is choosing to be outside society’s protection (of male institutions), and she therefore should choose to be with him, with what is “right.” He recognizes the power in woman-bonding and fears loss of her servitude and loyalty; the potential loss of his control. The concern is not affectional/sexual identity; the concern is disloyalty. The labeling is a threat…. Our concern with homophobia, then, is not just that it damages lesbians, but that is damages all women. We recognize homophobia as a means of controlling women, and we recognize the connection between control and violence.”

In a perverse sort of way, your husband’s comments were a gift. This is an opportunity for you to review your life, reflect on the script that was handed to you at birth, ponder your relationships, meditate on the image you are providing for your children, and evaluate who you are and what you want to do with the rest of your life.

The right frontal lobe of the brain is thought to be involved with figuring out answers to riddles: a different way to think about something. The first riddle describes the typical newspaper: white background, black print, and often read completely through. The second riddle requires thinking through the question. Mt. Everest is said to be the highest mountain on earth. Period. Before it was discovered it was still the highest mountain on earth.

Unfortunately, the typical school does not teach to the right hemisphere until subjects in the curriculum tend to appear in late middle grades and high school. The right hemisphere is larger at birth in boys and remains larger throughout life. (The left hemisphere is larger in girls and remains larger throughout life.) It is deadly when a set of fraternal twins start kindergarten together and the little girl handles reading, writing, and arithmetic quite well while her brother flounders until classes that use more of the right brain are introduced. That is thought to account for more boys dropping out of typical schools.

Ideas? It would be great if the curriculum was changed to start teaching to both hemispheres in kindergarten. Some studies estimate that the typical curriculum is a quarter of a century behind brain research. There is resistance to changing the curriculum because it will cost money. If you can find a male with a brain bent in the right frontal lobe to give Rolly a few tutoring classes and help him realize that he is not dumb, just being asked to learn subjects initially that are more difficult for him, he may relax a bit and start to thrive when the curriculum begins to add right-brained subjects.

Isn’t that a bit like looking at a map of the United States and asking someone, “Where do I go?” It depends on what interests you. If Niagara Falls interests you, then you wouldn’t likely go to Death Valley. What topics about brain function interest you? You might go to Article’s and select a topic from that section, or you might check out Practical Applications and select a topic from that section. Start almost anywhere and move on from there. Have fun with what you learn.

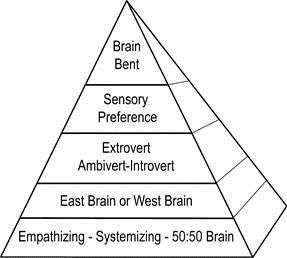

In a nut shell, the “Who I Am Pyramid” is a model to help portray key components of innate giftedness related to brain function. Each human being is a unique blend of at least five key brain-function components, each of which can be thought of as a separate overlay. This is one reason individual brains can differ so dramatically from one another. Learning by design begins with identifying and honoring each brain’s innate giftedness. This requires an understanding of these key components of brain function. They help to define one’s individual uniqueness, can help explain similarities versus differences, and can assist in developing strategies to enhance learning.

Learning can be defined as skills or knowledge acquired through instruction, study, or experience. Learning is impacted by the learner’s unique brain, tools that are available, and the teacher’s unique brain (if a teacher is involved). Even when these components are well matched with an undamaged brain, learning effectiveness may still be marginal due to a whole host of other factors (e.g., amount of sleep, type of food eaten, interest in the topic, past experience, presence of fear).

Miss one of these five key components in the learning environment and learning effectiveness can diminish. Miss two or more components and learning effectiveness can drop off dramatically!

Following are brief descriptions of the layers of the Pyramid, beginning with the first or functional layer:

Thinking Process Preference or brain lead. The brain’s relative energy advantage for processing information (what types of activities take the least amount of brain energy versus those that take 100 times more energy).