My nose presses against the glass as our plane begins its descent. I’m hoping to catch my first glimpse of one of the seven wonders of the natural world, having waited decades for this moment. Thirty miles away huge plumes of what looks like smoke billow into the air. Shivering with excitement, I recognize the plumes from pictures I have seen. It is not smoke, however. It is spray from Victoria Falls!

We fly low over the bush that extends as far as the eye can see. Its red-brown earth sprouts wiry grasses, and the landscape is dotted with umbrella shaped acacia trees, sturdy thorn bushes, and thickets. Off to one side is a family of elephants not far from a herd of Cape buffalos. In the distance a group of antelope (or wildebeests) are bounding over shrubs and thorn trees en masse, their hooves kicking up swirls of dust. Single dirt tracks appear, disappear, and reappear. Some drift into a kraal with its round thatched-roof houses, others into a tiny town, and some even melt away into the horizon. Suddenly, in the middle of nowhere, the airport looms into view. The runway rises up to meet us and we are in Zimbabwe, Africa.

After clearing customs I watch a group of men sing, dance, and drum on the entrance patio of the main building. Their costumes are a combination of animal skins and ostrich feathers along with spandex shorts. The performers must be in excellent physical condition because, although it is winter season, the sun is very hot during daylight hours, and they are not perspiring. We are!

I climb into the van that the safari company has sent to transport us from the airport, a distance of about 15 kilometers, into town. The driver frequently slows for wild baboons that are determined to cross in front of the van, for two zebras and several donkeys that can’t decide where the grass is greenest, for a stately Kudu whose spiraling horns reach up four feet or more, and for children in bright blue uniforms who are returning from school. We pass women carrying huge bundles on their heads. The driver says they can walk and balance those heavy head loads for kilometers at a time, and my own head aches with the very thought.

In town the driver stops at the booking office so I can reserve an elephant safari, while my cousins sign up for river rafting over category 4-5 rapids on the Zambezi River. Several passengers disembark, but we continue on to Victoria Falls Lodge, located about 10 kilometers out in the bush. Its draw includes the balcony restaurant and rooms that overlook a water hole. Sure enough, breakfasts and dinners are served to the real-time trek of wild life endeavoring to slake their thirst. Elephants, buffalo, warthogs, antelope, and birds of every size, hue, and description. Some of the egrets appear taller than I am. I pinch myself to make sure this is not a dream.

Early the next morning a safari van collects me from the lodge and an hour or so later, at the end of a single-lane dirt track, I have my first glimpse of the elephant conservation camp. Having never stood really close to a fully grown adult African elephant, I am a touch taken aback by their size. They are immense and easily more than twice my height! After an orientation and introduction to the eleven adult safari elephants, I climb to the top of a platform and take a look at what I will be riding for the next couple of hours. Jock is an immense bull elephant that came to the camp after being injured in a fight–or that is the assumption. When healed, the rangers released him back into the wild, but he reappeared at the camp four months later and so far has refused to leave. Jock seems to enjoy safari-ing people around on his back and helping care for other injured elephants.

One of the first things I notice is that Jock’s backbone seems to be sticking up some five inches above his body. As I maneuver myself onto his back I am vastly relieved to feel the foam rubber saddle between me and his back. My feet hooked in stirrups, it is very easy to adjust to the gentle rocking motion of his gait. The ground below looks very far away, however, and I am hanging on to the strap with both hands.

Jock’s driver, 22-year-old Krys, who recently got married and is the only person in his immediate family who has a job, rides in front of me. Krys gives Jock verbal instructions, often in English, to go forward, backward, to the right or left, plus foot and hand signals to keep him moving steadily along. Otherwise Jock might be tempted to dawdle. As it is he often veers to one side long enough to break off some foliage with his trunk and tusks. Shoving the whole thing–leaves, twigs, and branches–into his mouth, he chews as we walk along. Chris, who is from nearby Botswana and speaks Tsetswana, English, Afrikans, and some Xhosa (which is the delightful “click” language that I so much enjoy listening to), tells us that elephants typically spend up to eighteen hours a day foraging for food.

We also learn that Jock is about 38 years old and likely fathered one of the two baby elephants that tagged playfully along with us. They were born at the camp—after fifteen months of gestation. (And no, apparently there is no such thing as a gelded elephant.) Jock can gallop at rates up to 40 kilometers an hour, which is approximately 25 miles an hour. I sincerely hope that nothing startles him into a gallop since he is not equipped with seat belts, and the ground looks very far away! I look at his ears, lazily moving in the air like two giant fans made of thin leather. There are several holes punched along the edge of each ear at irregular intervals, and Chris explains that they were cut by thorns.

A junior elephant also trots along with our safari group, obviously not wanting to be left behind. This youngster had been found in the bush–a tiny baby standing forlornly beside the body of his dead mother, who was likely killed by poachers since her tusks had been sawed off. The camp elephants had welcomed the little guy with open trunks, while the rangers fed him every two hours around the clock. Junior had consumed 55 liters of formula per day until he grew old enough to start grazing and browsing. Krys explains that many such animals are not able to survive. He also tells me that some animals graze (e.g., antelopes) while other animals browse (e.g., giraffes). Elephants do both.

Back in camp I scoop up handfuls of special feed pellets and hold them out to “my elephant,” Jock. Most turned the tip of their trunks up so their riders could drop in the pellets. Not Jock. He “vacuumed” them from my cupped hands, the soft ends of his trunk passing lightly over my fingers checking for every last treat. His eyelashes were at least 2 inches long and thickly sprinkled along the lids of his rather small eyes. The baby elephants bump into us, wanting a treat, too, so I pick up some of the pellets that have fallen to the ground and share those. One of the babies is teething and holds it trunk back over its head hoping one of the riders will rub its gums. Stick my hand in your mouth?, I thought to myself. Cute as you are, I don’t THINK so.

The following day I finally get to view the falls up close and personal, the ones I have wanted to see since reading my first book about Africa at the age of seven. It was the story of David Livingston, a Scottish missionary-doctor turned explorer, who stumbled across the falls in November of 1855. Believed to have been the first European to see them, Livingstone promptly named them for Queen Victoria. Livingstone wrote: “No one can imagine the beauty of the view from anything witnessed in England. It had never been seen before by European eyes; but scenes so lovely must have been gazed upon by angels in their flight.” From that first tantalizing read, I had wanted to see Victoria Falls, and they did not disappoint me.

The indigenous people named the falls Mosi-oa-Tunya, which means the smoke that thunders. And thunder it does, so much so that it can be difficult to hold a conversation. A rainbow can be seen curving over Devils Cataract, above water that roars off cliffs from a relatively flat riverbed at the rate of nearly 40,000 cubic feet-per-second and drops 360 feet, throwing up billows of spray. Fortunately it is July, the beginning of the dry season, and the heavy mist, while visible, does not obscure a view of the falls, as can happen during the rainy season. By comparison Victoria Falls dwarfs Niagara Falls, the latter being only about half the height and width.

The western half of the falls are located in Zimbabwe, formerly known as Southern Rhodesia, while the eastern half are in Zambia, the former Northern Rhodesia. My brain is getting a work-out learning to pronounce and recall these more recent names! Dressed in a slicker and under an umbrella I walk along the observation path, although my gear doesn’t seem to prevent me from getting wet. The spray blows up, down, and every which way without apparent rhyme or reason. In fact, because of the continual spray-mist, the topography of the land is quite different right around the falls. It morphs from bush into more of a jungle, with thick foliage providing covering and camouflage for a myriad of wild things such as the family of warthogs—so ugly they’re cute–peaking out from under an elephant-leaf plant.

The chasm itself is relatively narrow (only 200-400 feet wide) with two towering islands: Cataract Island on the western edge and Livingston Island toward the middle. Anywhere you look the view is picture-perfect. The curving path leads to the Victoria Falls Bridge that spans the Zambezi River. It was the brainchild (the bridge, not the river) of Cecil Rhodes, a British-born South African businessman. Founder of the De Beers diamond company, which at one time controlled 90% of the world’s diamonds and now controls about 60%, Rhodes died before the bridge linking the two countries was completed. The Rhodes Scholarship, the world’s oldest and arguably most prestigious international fellowship, was another of his brainstorms.

The border post at this end of the bridge is for the town of Victoria Falls, Zimbabwe, while the border post at the other end is for Livingstone, Zambia. I watch foot, animal, and vehicle traffic traverse the bridge and wish I had time to walk across.

Way too soon I find myself back in the van heading for the airport. Once again the driver waits for baboons to wander across the road, and once again we slow for donkeys, antelope, warthogs, smaller buffalo, and pedestrians. I have fallen in love with the country, with the falls, with the animals, and with the people. I have exposed my brain to a myriad of new sights, sounds, smells, and tastes—my heart to as many emotions. I trust that millions of new dendrites have grown on my neurons to enrich their synaptic connections and to help age-proof my brain! As the plane hurtles into the air, my nose again presses against the glass for a last glimpse of the smoke that thunders, and I know already that I must return!

Emily Pauline Johnson, 1861-1914

It’s a magical place, sheltered by towering trees and soothed by a tiny bubbling spring that murmurs duets with the breeze. Just a stone’s throw from the road, it’s still easy to miss unless you know what you’re looking for. I stood there first more than a half-century past. My father, who loved Stanley Park in Vancouver, brought me to visit Takehionwake’s resting place, because I loved her poetry. Indeed, from my earliest memories I had been fascinated by this beautiful poetess—part Mohawk, part English, all Canadian.

The youngest of four, Pauline’s First-Nation name meant double life, a description that fit in many ways. Her parents were a Mohawk chief of mixed ancestry and an English immigrant. Although her parents’ marriage had been opposed by both families, out of mixed-race concerns, the Johnsons were soon acknowledged as a leading Canadian family, enjoying a high standard of living. The family home, Chiefswood, on the Six Nations Indian Reserve outside Brantford, Ontario, became well known and was visited by intellectual and political guests.

Now, once again, I was back at that magical place, kindness of my cousin Tim. The grandson of my father’s brother, it seemed somehow fitting that someone in my father’s line was helping me reprise my original journey. Standing beside the granite boulder, into which is carved a likeness of Pauline Johnson’s profile, bits of poetry came flooding back. Much of her writings spoke to my brain and heart in some way or another, but perhaps “The Song My Paddle Sings” most of all. Metaphorically it spoke of her own life, as she took responsibility for her poetry and fifteen years of public presentations, breaking the mold of the typical woman of that era.

Metaphorically it forecast some of mine. The realization that when the wind chose to blow—well and good, but it was somewhat capricious and could not be depended upon for sustenance and direction. For that, it was your own paddle, requiring the necessity of consistent effort in cooperation with the environment, and bringing the thrill of creativity, accomplishment, and reward.

And next, probably “Finale,” with its gentle and compassionate allusions to connection with nature, music, and friends. Johnson’s writing extended beyond that of poetry, however. Her book of stories about the Squamish people of North Vancouver, Legends of Vancouver, is still considered a classic of Vancouver literature.

With my family, I had moved half a dozen times or more by the time my sixteenth birthday arrived. As we packed and unpacked every few years, collecting and discarding, the one book with which I took exceeding care was Flint and Feather, a collection of selected Johnson poems.

I gazed at the granite monument once more, so congruent with its surroundings, so peaceful and yet so alive, so connected with the past and the present. My father had gone out of his way to give me an experience that had lodged itself in the deepest corner of my heart, the memories wrapped in part by his caring and in part by Pauline’s words.

Just the year before my father was born, Pauline Johnson died in Vancouver, British Columbia—of breast cancer. Her funeral, the largest to date in Vancouver, was held on her 52nd birthday. By 1921 a granite monument to her memory had been created in Stanley Park, beneath the murmur of the cedar trees, beside the bubbling of a tiny spring, amid the solitude of star-reflected light, beside the sea.

The inscription on her granite monument reads in part: In memory of one who’s life and writings were an uplift and a blessing to our nation. Ah, yes, as they have been in my life; as they have been to me.

Finale

The cedar trees have sung their vesper hymn,

And now the music sleeps—

Its benediction falling where the

Dusk of the forest creeps.

Mute grows the great concerto—and the light

Of day is darkening. Good-night. Good-night.

But through the night time I shall hear within

The murmur of these trees,

The calling of your distant violin

Sobbing across the seas,

And waking wind, and star-reflected light

Shall voice my answering. Good-night. Good-night.

—E. Pauline Johnson

The Song My Paddle Sings

West wind, blow from your prairie nest

Blow from the mountains, blow from the west

The sail is idle, the sailor too,

O! Wind of the west we wait for you.

Blow, blow! I have wooed you so,

But never a favour you bestow.

Your rock your cradle the hills between,

But scorn to notice my white lateen.

I stow the sail, unship the mast,

I wooed you long but my wooing’s past,

My paddle will lull you into rest,

O! drowsy wind of the drowsy west.

Sleep, sleep, by your mountain steep,

Or down where the prairie grasses sweep!

Now fold in slumber your laggard wings,

For soft is the song my paddle sings.

August is laughing across the sky,

Laughing while paddle, canoe and I,

Drift, drift, where the hills uplift

On either side of the current swift.

The river rolls in its rocky bed,

My paddle is plying its way ahead,

Dip, dip, while the water flip

In foam as over their breast we slip.

And oh, the river runs swifter now,

The eddies circle about my bow.

Swirl, swirl! How the ripples curl

In many a dangerous pool awhirl!

And forward far the rapids roar,

Fretting their margin for evermore.

Dash, dash, with a mighty crash,

They seethe, and boil, and bound, and splash.

Be strong, O paddle! Be grave, canoe!

The reckless waves you must plunge into.

Reel, reel on your trembling keel,

But never a fear my craft will feel.

We’ve raced the rapid, we’re far ahead!

The river slips through its silent bed.

Sway, sway, as the bubbles spray

And fall in tinkling tunes away.

And up on the hills against the sky,

A fir tree rocking its lullaby,

Swings, swings, its emerald wings,

Swelling the song that my paddle sings.

—E. Pauline Johnson

http://www.poemhunter.com/emily-pauline-johnson-tekahionwake/

I pinch myself. Yes! I pinch myself again. Yes again! It is not a dream. I am really awake and I am really here! I am sailing up the Nile—going south—on the MS Miriam.

Reclining against a bank of soft pillows in my ground-floor cabin, I watch an ever-changing panorama. Buildings of Luxor pass in and out of view, some new and some ancient. Women wash clothes along the river’s edge. Children play nearby, running through lush green vegetation or jogging along on the backs of little white donkeys. A gentle breeze ruffles curtains framing the picture window that occupies the entire wall. A felucca slips by floating north, with the current, its sail billowing gently in the wind.

White herons move stealthily among the bulrushes, multi-generational offspring of bulrushes that may have hidden the little Moses. Were similar storks stalking frogs the morning the Egyptian Princess reportedly found the babe floating in a basket? Beyond the belts of green that frame the Nile stretches the desert. That vast shifting region of sand and stone where not one blade of grass breaks the color scheme of beiges, browns, and grays. The desert begins as abruptly as the vegetation ends, the demarcation as sharp as a line drawn in the sand by a sharp stick. Lush green on one side; mysterious desert on the other.

My earlier trip to Egypt in the last century had centered on Cairo, Memphis, and Giza. On that occasion I had awakened the first morning to sunlight streaming in through a gap in the window coverings. Getting out of bed, stretching, wiping jet lag from my eyes, and pulling back the drapes, I had gasped. A great pyramid, holding nearly 5000 years of history, stared me in the face. And that was when, still in my travel night shirt, I’d fallen in love with Egypt.

Now, in addition to reprising visits to Cairo, Giza, and Memphis, my travels would expand southward to Luxor, Aswan, and Abu-Simbel. When I open the drapes this time, it is not to the sight of a pyramid but to that of a garden terrace sprawling across the back of the Cairo Marriott. Built around one of ex-King Farouk’s 19th century palaces, my room offers a view of gold filigree, Moorish archways, and tiled walkways. The entire compound is located on an island in the great delta that forms the gaping mouth of the Nile River. The longest river in the world, it meanders for a mere 4184 miles from one of its sources, Lake Victoria. Located within an elevated plateau in the western part of Africa’s Great Rift Valley, Lake Victoria is the continent’s largest lake and the largest tropical lake in the world. Its outflow in Uganda forms the Victoria Nile.

On the outskirts of Cairo stand the best known symbols of Pharaohic power and some of the most amazing treasures from the ancient world—the Egyptian pyramids and Sphinx. Built on the west bank of the Nile, the site of the setting sun, they were associated with the realm of the dead in Egyptian mythology. Most pyramids were built for the Pharaohs and their consorts during the Old and Middle Kingdom periods. Several of the Giza pyramids are counted among the largest structures ever built. The great Pyramid of Khufu, the largest and the only one of the seven wonders of the ancient world still in existence, still towers into the sky. Built of two-and-a-third-million blocks, each weighing several tons, it is no wonder that nine million visitors annually gaze with awe on the massive structure.

The light and sound show, playing on and around the pyramids scattered over the Giza plateau, transport us back eons: he grandeur of the Pharaohs, the mystery of their culture, the murmuring of secrets on the desert air, the wonder of papyrus, the chemistry of embalming… What a different world and yet somehow familiar: the quest for power, the intrigue of jealousy, the desire for immortality, the ego of legacy. Part and parcel of the human condition they’re all still here thousands of years later. Only the trappings differ.

Three days later I am heading to Luxor (formerly Thebes). Once we clear security at the Cairo airport, which makes American-airline security seem rather perfunctory, the flight is uneventful. From the window of the plane the delta below resembles a giant lotus flower in bloom, the symbol of Egypt on many an ancient temple column and source of a most fragrant essence.

The Program Director and guide assigned to our group is one of the best I have ever encountered. In his mid-thirties with a master’s degree in ancient Egyptian history, he is a veritable fount of information. His penchant for presenting details through stories and humor, in a voice as fluent in English as Arabic, albeit with a slight British accent, is easy to hear. Depending on the current state of the economy, tourism can be the number one, two, or three source of income for the country. Their citizens take it seriously, having experienced how quickly the numbers can drop. After the catastrophic tourist killings in the late 90s near Queen Hatshepsut’s Temple, for example, tourism fell to 3% of its typical rate and the government took immediate steps to enhance security for its visitors. Armed guards everywhere lend an oxymoronic presence—safety on one hand and window dressing on the other. Either way, their dazzling uniforms and military bearing lend pageantry to the panorama.

Hence an armed escort as we leave the Luxor airport and head for the MS Miriam, our home away from home for the next even days. That escort would be reprised many times during the week. Sometimes as a front-back vehicle escort to the Valley of the Kings, sometimes as an armed walking presence to the Sphinx, and sometimes as a plain-clothes detective riding in the bus itself. The soldiers, their crisp white uniforms gleaming ‘neath the desert sun, appear serious about their responsibilities (this is no time to crack jokes), while at the same time exhibiting the very soul of hospitality and assistance.

High minarets in every town and community mark local mosques. Five times each day from high towers the sound of chanted prayers float out on the breeze. Although our guide is Muslim he has a travel exception and can make up his prayers at tour’s end. At each destination the Egyptian people seem genuinely glad to welcome us to their area, pleased that we are interested in their country and culture. When they discover this is my second visit, they go out of their way to ensure I have a rewarding experience. No doubt my white-blond hair and obvious walking-stick help.

Aboard the MS Miriam,a typical Nile-River boat, a central ground floor reception area serves as the hub. Stairs lead down to the dining room, which means that passengers eat their meals below water level, waves lapping gently just below high windows. Stairs also lead up through two floors of river-boat cabins to the roof with its swimming pool and hot tub. Sitting beneath canvas canopies on Cleopatra-style chaise lounges, it is easy to picture royal barges traveling between Memphis and Thebes (now Luxor) and farther up river. I imagine Egyptian royalty sipping nectar from silver goblets nibbling fresh dates, pomegranates, nuts, baby bananas, olives, and you name it, while Nubian slaves wave giant feather fans to keep the air pleasantly stirred.

Below the high dam, settlements along the river banks are small. The farther way from Cairo, the more they are steeped in tradition. Children splash naked in the shallows unafraid, knowing that the famous Nile crocodiles live south of the high dam around Lake Nasser. Acres of sugar cane and date palms sway in the breeze. Bullocks, goats, donkeys, and the occasional camel graze on small patches of green that slope down to the river’s edge. How different from the teeming streets of Cairo and Alexandria where more than half of the 77 million Egyptians reside.

Side trips by camel, cart, cab, or carriage take us to view hand-woven carpets and papyrus pictures. At the perfumeries personnel dab drops of floral extracts on our skin so we can discover how the fragrance combines with our own unique chemistry—and love or hate the results. My favorite is essence of Lotus, the flower of Egypt. Its scent is both intriguing and seductive. We learn that most of the floral extracts are shipped from Egypt to Europe, diluted with water and alcohol, and resold at enormous prices under such exotic names as Emeraude, White Diamonds, White Shoulders, Evening in Paris, and Channel No. 5 for women; and under Eau Sauvage, Drakkar Noir, Obsession, and Eternity for men; plus new metrosensual offerings.

The temple of Karnack, situated at one end of the royal road that connects it with the Luxor temple at the opposite end, sets the stage for ruins to come. Scores of carved sphinxes line both sides of the royal road. One can only imagine how they looked in their heyday. Our guide, Mohamed (half the men in Egypt seem to be named Mohamed) makes it easy for us to grasp the procession of Egyptian dynasties—well, sort of. We begin to recognize the period of history represented by the style of carvings on pillars, statues, and facades.

On the opposite bank from Karnack, Queen Hatshepsut’s Temple sprawls in all its royal magnificence. We marvel at the sheer scope and magnitude of the architecture and also at the anger of Thutmose III, her stepson and successor. What must have happened between them to prompt the sixth Pharaoh of the Eighteenth Dynasty to systematically deface all her statues and monuments? How he must have hated her! The style of the temple and drawings of pools and plants that formed part of the original landscape were innovative for their time, to say the least. They were a definite departure from some of the other ruins we had already viewed.

Five o’clock in the morning. The phone rings, my cue to fall out of bed, dress in long-sleeved cotton, and go down to breakfast. Although it is fall in Egypt, heat from the sun, in the Valley of the Kings can be blistering by early afternoon. Our guide wants us on the bus by 7 o’clock so we can be finished sightseeing by noon.

Escorted front and back by military jeeps, our bus winds through rocky desert for nearly an hour. As our eyes become adjusted to the terrain, it becomes easier and easier to spot openings that dot the hillsides; burial chambers of governors and other nobility.

Tombs in the Valley of the Kings are spacious, as unlike the cramped tunnels and underground burial chambers of the pyramids as night is from day. The tombs are in the desert, however. Not a blade of green is visible as we leave the bus and begin a half-mile sloping walk up to a cluster of tombs.

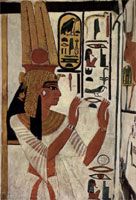

Carved into solid sandstone and protected from the elements for thousands of years, many paintings inside the tombs are still vibrant with color. We recognize some of the hieroglyphs through Mohamed’s stories. The sarcophagi that remain are massive and magnificent. What a feat to have transported them down the Nile by barge, up the desert hills for kilometers, and finally down the decorated hallways to their final resting place.

Small rooms carved off the main tunnel were once stuffed with everything and more that the resident of the sarcophagus might possibly need on his/her journey through the underworld to the next life. Little if any treasure remains in the actual tombs, but after marveling at them in the Cairo museum, it’s easy to imagine how the storerooms must have looked.

Smart man, our guide. We appreciate Mohamed’s foresight as we leave the tombs and see busloads of tourists just arriving in the Valley of the Kings. It is hot and we eagerly drain the bottles of water the bus driver provides. Now to reboard the MS Miriam for a late lunch and siesta. Tonight is another adventure of sound and light with the option of a folklorico. Belly dancing—it takes years (so they say) to gain the precise muscle control required. Not in my lifetime!

In an ancient quarry near Aswan, we view an unfinished obelisk. Planned to be the largest ever quarried in Egypt, it lies there, all 137 feet of it at an estimated 1100 -1200 tons. Cracked down the middle, it was never finished. It does provide insight into how existing obelisks were created, however. But how would the workers have lifted it from its bed, gotten it down to the Nile, and then transported it to its designated location? It boggles the mind!

Back on board our Program Director gathers us in the main-floor lounge for a lecture about Egypt. For example, back in the mid nineties the literacy rate was something like 15% (could we have heard that correctly?). With a massive educational push and required school attendance estimates are that two-thirds of the people are now literate. Private schools are welcome as they reduce the strain on government schools. Again, however, the father away from Alexandria and Cairo, the more likely one is to discover pockets of illiteracy and a clinging to old customs and traditions that are no longer practiced in urban centers. He invites questions and is willing to answer any and all of them.

The captain navigates a set of locks on route to the Aswan High Dam. It was that and more—high and massive! Built by Nasser with aid from the Soviet Union (after Britain and the United States backed out from initial offers of financing), it changed the face of agriculture along the Nile. The dam—3,830 meters in length, 980 meters wide at the base, 40 meters wide at the crest, and 111 meters tall—forms a reservoir known as Lake Nasser. Now the country is no longer at the mercy of the annual spring floods. Crops are grown year around watered by irrigation canals, and electricity reaches even the smallest Egyptian communities.

At the Aswan airport, we board a plane that flies us into the region of Nubia. While it is virtually impossible to select a “best of show” the two massive rock temples at Abu-Simbel have to be near the top. Built by the third Pharaoh of the Nineteenth Dynasty, the structures are Herculean in scale and overwhelmingly impressive. Touted as Egypt’s most powerful ruler, Ramesses II has been associated traditionally with the Exodus and the emancipation of the Israelite peoples from slavery, the story of which forms the basis for the Jewish holiday of Passover.

Nefertari is known from the many paintings that adorn temple and tomb walls. Her burial chamber in the Valley of the Queens, built by Ramesses II, is reportedly the most beautiful of them all. Even her name is said to mean “the Most Beautiful of Them.” Our guide tells us that so far as it is known, no other Egyptian queen was held in such honor that a temple was dedicated to her jointly with a goddess.

The engineering that first carved the elaborate temples and all their columns and figures from solid rock in the 13th century BC beggars the imagination. The technology that lifted the two structures out of harms way in the 20th century AD is equally astounding. But for the far-sightedness of archeologists and the generosity of art lovers such as Jacqueline Kennedy Onassis, the great temples of Pharaoh Ramesses II and his beloved royal wife Nefertari might have disappeared forever beneath the waters of Lake Nasser behind the high dam.

The salvage operation itself began in 1964 and continued until 1968. Dismantled and raised over 60 meters up the sandstone cliff from the spot where they had been built more than 3,000 years earlier, the two temples were reassembled in the exact same relationship to each other and the sun and covered with an artificial mountain. It is difficult to stop staring.

After lunch we climb aboard a felucca. Its white sails catch the breeze and float us past the Aga Khan’s mausoleum and white villa on the west bank of Aswan. We sail around lush botanical gardens on Kitchener’s Island, so named because the British Consul (Lord Kitchener) was deeded the island by the Egyptian government in recognition of successful 19th century campaigns in the Sudan, far bey ond the high dam.

We dock at Elephantine Island. The oldest ruins still standing on this largest island at Aswan is a step pyramid dating back to the third dynasty. Disembarking, we ride the elevator in a luxury high-rise hotel for aft ernoon tea on the top floor. The 360-degree panorama matches the exquisite repast.

At ground level again, a quick trip by water taxi returns us to the MS Miriam. All too soon the captain fires its engines, makes a U-turn and we are floating down the river going north. Once more through the locks, past a myriad crumbling ruins to the dock at Luxor, and on to the airport for a return flight to Cairo. Only a few more days in Egypt.

Early morning and I’ve just finished my last breakfast at the palace. The van makes its way through the Cairo traffic toward the airport. At least five lanes of seething traffic crowd into four official lanes. On exit streets anything goes from donkey carts to tankers. The mules must have nerves of steel. Their funny little tails whirl a mile-a-minute as the animals plod along unconcerned midst camels and cars, negotiating their antique-modern world. All too soon I am once again passing through multiple security checkpoints on my way home.

Aboard the plane, I press my eye to the window to catch a last glimpse of Egypt’s meandering delta, fanning out below like an opening Lotus flower. I think I recognize the island from gold trim on the palace reflecting sunlight. One by one the pyramids fade into mist and haze. Finally all that’s really distinguishable is the ribbon of water flanked by twin borders of green. And beyond on either side, the desert as far my eye can see. The Valley of the Nile, one great museum. What secrets it still holds with perhaps 70% of its estimated treasures still undiscovered.

The plane bursts upward through a light cloud layer and the continent of Africa disappears from view. I still look out the window, hoping for a last glimpse of Egypt. My brain, stimulated by sight, sound, scents, stories, and scenery, has sprouted millions of new dendrites, What is it about this region that calls to me? Mayhap some ancestor traversed this land and bequeathed my cells with memory. All I know for sure, and “I know that I know that I know,” (smile) is that I already want to return.

Half-way around the globe and back home in Northern California, I stand in the hallway surrounded by a small collection of Papyrus paintings. One shows my name in hieroglyphics written inside a cartouche. Looking into the glass my mind’s eye sees again ancient pyramids of Giza, pictures the Valley of the Kings with its hidden tombs, imagines the great sphinx gazing steadily into eternity, visualizes the temple of Queen Hatshepsut with a camel caravan poised against the setting sun, and marvels at Abu-Simbel. Always Abu-Simbel. I hear myself sigh. I have fallen in love all over again—with Egypt. Gentle on my mind.