Hear the word holidays and the word stress often follows quickly in its wake. Examples abound. I observed these three quite recently:

Stress is simply the word for what happens when you ask your brain and body to adjust to a change. Asking your body to move from one chair to another is stressful—a request for change. Having said that, stress is part of life and lets you know that you are alive. The absence of stress is death.

Any change in routine can be a stressor. Since holidays usually involve changes in routine, they can contribute to one or more of the following types of stress:

According to Webster’s Dictionary the word holiday denotes a time when one is exempt from work, or an opportunity to commemorate an event or a period of relaxation¾even a vacation.

The word stress, on the other hand, refers to a state of bodily or mental tension resulting from factors that tend to alter existing equilibrium (balance). That makes the term holiday stress something of an oxymoron—a combination of incongruous words. It also helps to explain the reason that something designed to be relaxing can end up being a major stressor. It is difficult to commemorate an event with relaxation and pleasure when you are in a state of bodily or mental tension!

Think about your most stressful holiday. What is your history related to this holiday? Is it good, neutral, or awful? Rate it on a scale of 1 to 10, with 1 indicating abject dread and 10 indicating joyful anticipation. You may find it helpful to use the Holiday Stress Grid that follows.

Someone asked me the other day if my holiday memories were positive, negative, or neutral. Pondering that question, it quickly became clear that mine were a mixed bag. During part of my childhood we lived on the Canadian prairies. My brother and I joked that we could expect about three days of hot weather each year. Memorial Day weekend was a signal that summer might be just around the corner. If the weather cooperated we could wear short sleeves and pedal pushers to the annual spring picnic, and start on a tan. Memorial Day weekend was definitely a favorite!

December holidays were a different story! They arrived with snow and more snow, often piled higher than a horse’s head. And with the snow came wind. Sometimes it coated bare tree limbs with shimmering hoarfrost or drove ice crystals through the tiniest cracks in doorjambs and storm-window frames. And the cold. Relentless, bone-jarring, unforgiving, biting, 30-or-40-degrees-below-zero cold! Curled up with a favorite book in front of the fireplace (if there had been a fireplace in our home) would have been one thing. Bundled in layers of protective gear and going from house to house singing carols and requesting donations for food baskets was another. No, December holidays were not a favorite of mine!

Which holiday or celebration event is most stressful for you? Think beyond national celebrations—Christmas/Hanukkah, New Year’s, Cinco de Mayo, Thanksgiving, Memorial Day, July 4th, or Labor Day. Any event that commemorates something important or momentous in your life may actually have a greater impact on your brain (e.g., the anniversary of a birth, adoption, marriage, divorce, miscarriage, layoff, bankruptcy, or death).

Every brain on the planet is believed to be different in structure, function, and perception. This means that your perception of what constitutes holiday stress and the magnitude of its impact will be unique to your brain, as well. Your perception will be influenced by a whole host of factors, including your own innate giftedness (e.g., individuals with introverted brains may find holidays to be overstimulating and energy-exhausting), past experiences, expectations, beliefs and attitudes, perceptions, and personal preferences, to name just a few.

Strategies for handling stressors need to work for your brain. Some have estimated that half of most people’s problems result from the way they think. Hmm-m-m. Imagine changing the way you think about holiday stress and dropping half the problems off the back of your metaphorical turnip truck.

You may have approached your most-stressful holiday or celebration event from agrin and bear it stance—if you couldn’t avoid it altogether you just tried to survive the inevitable. Unmanaged holiday stress can contribute to everything from depression to death. There can be a better way. Managed effectively, these celebration events can add spice, enjoyment, and meaning to life. Give yourself five gifts and a lagniappe….

#1 – Manage Your Expectations Carefully and Realistically

Everyone has expectations. Period. They can perhaps be most harmful when you don’t realize you even have them, have not identified them consciously, or have no plan for dealing with them efficaciously. Your learned responses related to expectations may be causing you needless stress.

Holidays and other anniversary events typically involve traditions and rituals. Many expectations revolve around traditions and rituals. Whether or not they’re functional and desirable or have completely outlived their usefulness, traditions and rituals are powerful—so powerful that in some cultures they can result in death.

Jot down your expectations. Are they mature, realistic, and doable? If not, revise your expectations and post them where you can see them easily. Make a clear decision to be true to them. You may need to do some pre-holiday negotiations and implement more appropriate personal boundaries.

An ounce of prevention before the holiday arrives is worth ten pounds of cure afterward.

For example, if you expect Great Aunt Lily to affirm everyone in general and you in particular, even though she hasn’t thrown a kind word anyone’s way in 50 years, your unrealistic expectations can set you up for major stress. If you expect your erstwhile nephew to show up stone sober, even though he’s been spiflicated at every family gathering his entire adult life, get ready for stress!

If, on the other hand, you expect the usual and set personal limits that work for you, any improvement in the situation or behaviors can be viewed as a bonus.

The words of Kahlil Gilbran speak eloquently to expectations:

We choose our joys and sorrows—long before we experience them.

Create and implement realistic expectations. Avoid getting caught up in the agendas of others or sucked into hype and commercialism. Above all, expect to be successful!

#2 – Learn to Upshift Quickly

According to my mechanic, an automatic transmission is designed to use the most efficient gear for the specific environmental conditions. Compare the three functional layers of your brain to an automatic transmission with three gears. Under situations of trauma, threat, or crisis¾when the going gets tough¾the brain tends to downshift looking for functions to promote safety.

Whether it is your vehicle’s automatic transmission or your brain’s ability to refocus energy and attention, downshifting is helpful when used appropriately. Under the doctrine of “you usually give up something to get something,” when your brain downshifts unnecessarily or stays downshifted for too long, you may:

It is important to recognize when your brain has downshifted so you can upshift as quickly as possible. To do this, increase conscious awareness of your own key stressors, patterns, and symptoms:

Getting a handle on your stressors, patterns, and symptoms is a form of insurance. You are ready for whatever happens. This knowledge can serve as an early warning system to alert you when your brain downshifts. Then you can implement your preplanned strategy to upshift. Over time, conscious awareness can kick in about the same time as the first stress symptoms make their appearance.

Dig to uncover core issues. Be honest. Create a collage of what happens to your brain and body when you are confronted with holiday stressors. Picture in your mind’s eye what your body looks like and how you behave. Create a new picture of what you want your body to look like and how you want to behave. This gives your brain a map to follow. With a bit of forethought you may be able to avoid a specific stressor altogether, limit your exposure, or minimize the stress reaction.

Develop a pre-planned strategy to get your brain upshifted. The fastest way for me to upshift is to think of something humorous—and then choose to laugh about it. Both those functions reside in the conscious thought part of the brain: third gear, if you will. If I can recognize something is funny and can choose to laugh about it, I’m upshifted.

#3 – Reboot Your Brain with Brain Breathing

Using the metaphor of a computer, learn to reboot your brain. At the first sign of a stress symptom, break the cycle¾within the first 6-7 seconds if possible. The sooner you do this, the fewer stress symptoms you’ll likely experience. You may be able to avoid downshifting altogether or at least return quickly to an upshifted state.

Brain breathing is a simple technique that can be used almost any time, anywhere, and can be accomplished in a matter of seconds. It is designed to ensure that a sufficient amount of oxygen gets into your blood stream. As you may know, oxygen comes into your lungs through the air you breathe and is then transferred to red blood cells that transport the oxygen to cells in your brain.

Growing up, you may have been taught that the best way to breathe was to stand up straight, stick out your chest, and hold in your abdomen. It turns out this is not an optimal position for deep breathing. Abdominal breathing is the ticket!

The formula for brain breathing is:

At the first sign of a stress symptom reboot your brain by brain breathing. As a preventive tonic, I usually take a dozen brain breaths every day, preferably in pure fresh air. If someone asks me what I am doing I respond, “Brain breathing. Please join me.”

#4 – Hone Your Emotional Intelligence (EQ)

Emotional intelligence—the ability to bring intelligence to your emotions—is important to your overall success in life. It may even be more important than I.Q. Emotions are internal signals that alert you to what is going on around and inside you. They connect your subconscious with your conscious mind and give you information and energy with which to manage a variety of situations safely and appropriately.

You are much more likely to store information in long-term memory when the encounter contains an emotional component. That’s likely why holiday memories can be so impactful—euphoric or abysmal! Ignoring your emotions or pretending they don’t exist is generally unhelpful. So is permitting them to take over your life. Emotions are just signals.

When you react out of proportion to any given situation, the overreaction usually relates to the past and may have little, if anything, to do with the current moment. In other words, the reason is never the reason. Something about the present situation reminded your brain of something in the past, and brought the emotional force of that memory to bear on the present moment.

If you catch yourself beginning to overreact, stop, breathe, observe, and evaluate. Ask yourself what there is about this situation that may have reminded your brain of something from your past? Identify that “something,” bring it to conscious awareness, and deal with it appropriately. Consciously working this process can help increase your level of EQ.

Marcus Aurelius taught that when you are upset by anything external, the pain is not due to the thing itself but to your own estimate of it. You have the power to alter your estimate (thoughts about it) at any moment. When confronted with a stressful situation, I have found it helpful to imagine the worst thing that can happen, decide if I can live with it, and then take appropriate action to minimize negative outcomes. Actually, the worst-case scenario rarely materializes.

#5 – Keep Your Life in Balance

A balanced, high-level-wellness lifestyle is important all the time but especially necessary during holidays. Determine to take good care of your brain and body¾and then actually do it! Make generous deposits into your stress-prevention bankin terms of sufficient sleep and relaxation, adequate water intake, daily exercise, nutritious food, positive mindset, humor, play, and nurturing relationships (e.g., friends, co-workers, family/family-of-choice, partner, Higher Power) just to name a few.

Be judicious about your intake of caffeine, sugar, and alcohol. Avoid placing yourself in situations that you know from past experience either push you to get out of balance or are likely to trigger a stress response.

Illness, minor injuries, accidents, and depression often increase during or following holiday periods. This is often due, at least in part, to allowing some aspect of life to get out of balance. It’s much easier for stressors to trigger illness or overreaction when you are living an unbalanced life. Even a good thing taken to the extreme can be detrimental. Treat yourself to a consistent high-level wellness lifestyle. It’s great insurance and can pay huge dividends over time.

Lagniappe – Live the 20:80 Rule

The word lagniappe (pronounced lan-yap) first crossed my conscious awareness some years ago in New Orleans. During a tour of antebellum homes, pre-Katrina, my guide explained that she was giving us a lagniappe. She went on to say that this Creole term meant something special, a little bit extra, or an unexpected surprise. On that occasion, our lagniappe was a delicious Louisiana pecan praline.

Think of the 20:80 Rule as your lagniappe. It represents wisdom that Epictetus shared with the world more than seven centuries ago. This philosopher believed that only about 20% of the impact to your mind and body was related to the event (i.e., what happens to you), while 80% was due to your perception of it (i.e., the importance you assign to it).

The 20:80 Rule is an elegant way of saying that holidays and commemorative events will likely be a stressor in some way or another. The event represents the 20%. You may not choose to—or even be able to—eliminate the 20%.

What you think about the event, the weight you place upon it, and the importance you assign to it represents the 80%. You can do almost everything about the 80%.

Actually, one of the few things you can control are your thoughts. You can exercise a surprising amount of control over stressors by managing your thoughts and, if necessary, changing the way you think. That’s the difference between efficiency (doing things correctly) and effectiveness (doing the correct things).

You can reframe the importance. When you clearly understand that anything that comes out of another person’s brain is only that brain’s opinion, you will likely avoid arguing, stop taking things personally, and actually get a chuckle out of many situations. Another brain’s opinion has nothing to do with yours unless you choose to make that so.

The 20:80 Rule was the ticket recently when I brought my “famous” cherry-apple pie (well, some of my family and friends call it that) to a community potluck. Over the dessert table a casual acquaintance asked, “Did you put sugar in your pie?”

“Yes,” I responded. “It contains Xylitol.)

Without even a pause to take a breath, the individual continued with, “Well! If you had any brains you should have known that I was recently diagnosed with diabetes and can’t eat sugar. And if you had any milk of human kindness flowing through your veins you would have made the pie sugarless for my sake!”

I blinked, chuckled, and applied the 20:80 Rule. “Thank you for sharing that information with me,” I said. “Another time let me know in advance that you will be present and if I’m able to attend I’ll bring a sugarless dessert.”

Now it was her turn to blink. She did, twice, and then said, “Well, that doesn’t help me today.”

“You’re right,” I agreed. “It doesn’t help you today, at least not for this pie.” End of discussion.

Did I enjoy her confrontation? Not particularly. Did it knock me off center and ruin the event as it might have for me half a century ago? Heavens no. It was just her brain’s opinion, unique to her, and I could choose to pick it up or let it go. I chose to let it go.

Give yourself these five gifts and a lagniappe. When practically applied, they can make all the difference in your response to holiday stressors. Come to think of it, they can make all the difference in the rest of your life!

Holiday: Write down the name: | History: [ ] Good [ ] Neutral [ ] Awful | Stress Scale: 1 Minimal | Your Present Expectations:

|

Are your present expectations mature, realistic, and doable?

If not, how you could reframe your expectations?

Write down one strategy you can implement now:

How can the 20:80 Rule help you with this strategy?

| |||

Scene One – Hospital Employee Lounge

“Holidays are absolutely the worst!” exclaimed Nell, sinking into a recliner and covering her face with her hands. “Everyone but everyone scurrying around like rats abandoning a sinking ship. I wish I could avoid them all.”

“What?” asked a colleague, sipping coffee and nibbling on a donut. “Holidays, rats, or a sinking ship?” Everyone chuckled. Even Nell.

“I’m with you,” said Hans, sliding off his stool. “They’re all the pits: rats and holidays, to say nothing of a sinking ship!” He paused just long enough in his stride to throw a crumpled sandwich wrapper into the trash bin and hold open the door for an incoming lab tech.

“We sure see the outcome of holiday stress,” commented the nursing supervisor, opening a Chinese carry-out container. “Especially in the Emergency Department and Mental Health. Cardiology, too, for that matter. And the Intensive Care Unit… Most everywhere, actually.”

Scene Two – Hospital Staff Cafeteria

“How is it,” asked an endocrinologist of the next person in line as both inched along the serving line, “that the words holidays and stress have come to be inexorably linked together?”

The pathologist laughed. “Your guess is as good as mine―or better. After all, you see the people who’ve developed serious problems due to the negative stress but who are still alive. Me? I meet ‘em in the morgue after the stress has done for them but good.”

“You mean bad,” snorted a security officer, entering the conversation while waiting to swipe an employee badge. “Or after too much alcohol or other recreational drugs dulled their brains into driving dangerously.”

Scene Three – Hospital Chaplain’s Office

“Holiday stress. Bit of an oxymoron, that.” The visiting cleric sighed. “A holiday is supposed to be a time of happy relaxation. Stress, on the other hand, at least undesirable stress, connotes tension or anxiety from whatever has altered one’s equilibrium. Hard to relax when you’re in a state of bodily or mental tension. Impossible to have fun.”

The chaplain nodded. “I always put in some of my longest, saddest, and most stressful hours around holiday seasons.”

Ponderings

Are hospital employee lounges, staff cafeterias, and chaplain offices the only places where conversations about holiday stress typically occur?

Quite unlikely.

Similar scenarios abound. My brain’s opinion is that the stress has everything to do with expectations: yours as well as those of others. It often comes from just running on the treadmill of life and failing to take time to analyze not only what is really important to you personally but also how you can extract the meaning of the holiday season without getting caught up in all the decorating, merchandizing, and partying melodrama.

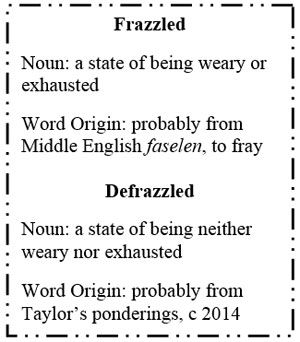

The paradox is that holiday frazzle can even come from following “traditions,” giving little if any thought to whether or not they still work for you—if they ever did.

A few decades ago, several bouts of post-New Year’s pneumonia brought me up short. (Laid me out short, I should say.) You can get out of a trap only when you figure out that you’re in one. I decided enough was enough.

So, what have I learned about holiday frazzlement, negative stress, and wellness?

Did you find yourself frazzled during the holiday season just passed? If so, your best option is to break the cycle: De-link the all-too-predictable outcomes of holiday burnout. An ounce of prevention is worth ten pounds of cure after it’s over. Plan today for this year. Then, right after the next holiday season has passed, for the following year. Decide now what you are going to do differently then.

Metaphorically, turn down the volume on the seasonal noise, starting with negative conversation. In “The World According to Mister Rogers,” Fred Rogers calmly reminds both children and adults:

In times of stress, the best thing we can do for each other is to listen with our ears and our hearts and to be assured that our questions are just as important as our answers.

We humans spend a relatively short amount of time on this planet. What is your track record with holiday frazzle and stress? Remember: A rat race is for rats only!

Concentrating on what is really important can make all the difference in the world. You just might start anticipating holiday seasons with less dread, more delight. Have happy holiday seasons from here on out. Choose to live defrazzled.

I sure do—now!

“Okay,” Harvey said, setting his laptop on the dining room table, “I’m off on an internet search about the BBB, as our visiting professor referred to it this morning. I need to write 500 words for class tomorrow. Good thing I can do a search right here at home.” Harvey powered up his Latitude.

“Are you talking about the Better Business Bureau?” his wife asked.

Harvey looked up from his laptop, a puzzled expression on his face. “The Better Business Bureau? What’s that got to do with our neurophysiology lab?”

“I thought that’s what BBB stood for,” said his wife.

“Oh! No!” said Harvey, dissolving into laughter. “Sorry. Blood Brain Barrier. That was a good guess, though. The prof explained the BBB as a method of ‘separating circulating blood in the capillaries from the extracellular fluid in the brain and central nervous system,’ as he put it.” And Harvey was heads down again surfing the Internet for relevant information. “Boy,” he exclaimed a few moments later. “This is really interesting stuff. Talk about a Star-Wars-type shield!”

Of the estimated 60,000 blood vessels (arteries, veins, and capillaries) that run throughout the human organism, about 400 miles of vessels are found within the human brain. What Harvey found in his internet search was that the Blood Brain Barrier or BBB, is a marvelous piece of workmanship. During the first trimester of gestation, all vertebrate brains develop a protective covering that occurs along all capillaries and is designed to create tight junctions that, in effect, join the membranes together so closely that they seal the capillary walls, forming in effect a virtually impermeable barrier to fluid.

Most capillaries contain slit pores so molecules can diffuse easily from the tiny blood vessels out into the surrounding tissues. They function much like a soaker hose would in your garden. BBB capillaries have no slit pores. Instead, they are lined with tight epithelial cells to help prevent molecules from diffusing out. In addition, glial cells, neuron helpers that may actually outnumber neurons in the brain, provide additional protection. The most abundant type of glial cells in the brain and central nervous system or CNS, these glial cells are known as astrocytes because of their characteristic star-shape. A matrix of fibers lining the interior surface of the blood vessels, also plays a part.

The specialized capillaries, and astrocytes (glial cells), and the fiber matrix are primary components of the BBB. It is designed to shield the brain from viruses, toxins, and other potentially harmful large molecules, as well as unpredictable fluctuations in a variety of body substances. The shield prevents stuff that is able to get into the blood stream from being passed into the brain and central nervous system.

Enter stressors.

The brain is the first body organ to recognize a stressor and it does so almost instantly. When this happens, the brain triggers the release of a cascade of stress hormones such as adrenalin and cortisol to assist in managing the stressful event. The brain and body are an integrated system, working together, hand in glove. Stress hormones were intended to help the brain and body respond effectively to stressful events; they were never intended to be triggered ongoing.

Within the brain itself, the hippocampus, the brain’s search engine, may be the most susceptible to these stress hormones. (Hippocampi, really; two little identical brain organs in the mammalian or second layer of the brain.) High levels of stress hormones can eventually kill brain cells in the hippocampus, which can interfere with its function. This may show up in a specific brain as a decreased ability to learn new information, to transfer information from short- to long-term memory, and to recall stored information.

During the Persian Gulf War, Israeli soldiers received pyridostigmine, a drug that attaches to receptors on nerves located outside the central nervous system (CNS). When chemical weapons invade the body, they are unable to find any open docking stations (bind to the receptors) because they are already occupied with the drug pyridostigmine. This limits the ability of chemical weapons to cause damage. Normally, only very small amounts of pyridostigmine make it across the BBB. During the war, about twenty-five percent of the soldiers who had received this drug complained of neurological symptoms including headaches and drowsiness. The symptoms would likely occur only if the substance had crossed the BBB. By way of comparison, during peacetime when researchers gave this drug to another group of soldiers, only eight percent reported any symptoms.

Physicians performed similar studies with mice. The research animals were forced to swim for two four-minute intervals. The control group were not required to swim. It required over 100 times more pyridostigmine to penetrate the brains of unstressed mice compared to the mice that were required to swim. The researchers repeated the study using a large molecule of blue dye and found similar results. Substances that should not have crossed the blood-brain barrier appeared to do so under conditions of stress.

The conclusion?

Stress appears to increase the permeability of the BBB. Stated another way, stressors have been found to increase the ability of molecules to cross the BBB, sometimes rather dramatically. As the BBB becomes more porous, unwanted molecules are able to get into the brain and wreak all manner of havoc. This also leaves the brain vulnerable to unpredictable fluctuations in a variety of body substances including excess stress hormones, which can even increase one’s risk of stroke.

“So, Harvey,” his wife asked a couple hours later, “what did you learn?”

“How much time do you have?” asked Harvey, stretching happily. “For one, hormones are very powerful. For another, you must have stress hormones to live but too many of them appear able to weaken the BBB. The result of increased BBB permeability could even impact your longevity.”

Harvey was correct on all accounts. You cannot live without stress hormones but they can have a cumulative effect, similar to that of repeated exposure to radiation. And yes, hormones are exceedingly powerful. When adrenalin and cortisol are released in a sudden rush, they can create an internal chemical tsunami. And it can be equally problematic when they are released chronically in amounts that put the body’s levels out of balance.

“Here’s my closing sentence,” said Harvey, as he hit the print button on his laptop: “Learning to recognize stressors quickly and managing them appropriately, along with doing whatever you can to rebalance out-of-balance hormones, are critically important strategies for life and health. You can help protect your BBB!”

“What do you know about Takotsubo?” asked Nell, putting down the newspaper. “There’s an article about an unexplained death that some think might represent that syndrome.”

Nell’s mother, an Emergency Department nurse, said, “I’ve only seen one case so far, and the doctor referred to it as a broken heart cardiomyopathy.” She went on to share what she knew about this interesting and rare condition.

Takotsubo is a Japanese word describing a distinctively-shaped fishing pot used for trapping octopus. The label broken heart cardiomyopathy refers to the fact that the left ventricle of the heart takes on the shape of this fishing pot when major stressors impact the heart, likely due to the secretion of stress hormones. The syndrome was first described as a case study in Japan. Although a rare syndrome, several reports or cases have surfaced recently in other countries. In some of the cases involving an individual with reported or suspected Takotsubo (or broken heart syndrome) the person survived in the short term, although long-term prognosis is unclear. In other cases, the syndrome resulted in the death of the individual.

Society often speaks poetically and sometimes blithely of a “broken heart” but as is so often the case with metaphors there is some basis in fact. Takotsubo cardiomyopathy (also known as transient apical ballooning syndrome, apical ballooning cardiomyopathy, stress-induced cardiomyopathy, Gebrochenes-Herz-Syndrome, and stress cardiomyopathy or broken heart syndrome) is the label that describes a heart event in the absence of any significant coronary artery stenosis. Several cases have been cited in the literature and it has been suggested that emotional stress may have precipitated the symptoms that mimic acute coronary syndrome. Some of the instances reported included:

The brain and body are an integrated system. They rely on a series of chemicals to carry out all of its essential functions. Neurotransmitters and hormones are the chemicals that control every system and process within the body. These chemicals are powerful, especially the stress hormones of adrenalin, norepinephrine, and cortisol.

Adrenalin

Adrenalin is responsible for a whole host of changes in the brain and body including providing energy to take necessary action. Temporarily it increases mental alertness, impacts moods, and helps one tolerate physical exercise. And when the demand for adrenalin exceeds what the adrenal glands can product, a whole cascade of undesirable consequences can result ranging from chronic fatigue and dark circles under the eyes to increased sensitivity to chemicals and toxins and brown spots on the skin. Some individuals exhibit behaviors designed to pump out additional adrenalin engaging in everything from arguing to physical fighting.

Norepinephrine

Norepinephrine is both a neurotransmitter and a hormone. As a result, its role within the body is essential to normal body and brain function, playing a significant role in how the body responds to stress. The body’s “fight-or-flight” response is coordinated by both adrenalin and norepinephrine (or noradrenaline). Secreted by the adrenal medulla glands, norepinephrine is more involved with maintaining normal body functions like heart rate, blood pressure and sugar levels than responding to perceived threats. In the brain it impact areas that regulate sleep, attention, learning, and emotions. It stimulates both the emotional and cognitive centers of the brain and when produced in normal amounts, can create a sense of well-being, as well as euphoria.

Cortisol

Cortisol is essential for life. Either too little or too much can result in problems. One of tis jobs is to maintain the lower parameters of blood sugar (insulin regulates the upper parameters). Cortisol will actually elevate in an attempt to bring up a drop in blood sugar back into a normal range. Since the brain requires an ongoing supply of glucose and gets most of its energy from glucose, the maintenance of adequate blood levels is a top priority of this stress hormone. There is some evidence that managing cortisol is learned over a period of repetition of from several months to years (e.g., some people create chaos in order to release cortisol). It requires a minimum of four months to address cortisol imbalances.

When stress hormones are released, they impact every cell in the body. A little goes a long way. When stress hormones are poured out in high doses, they can create an internal tsunami, so to speak. In the presence of major stressors (including internal physiological stress due to imbalance), these stress hormones can cause the left ventricle to balloon out, which interferes with the smooth functioning of the heart.

Takotsubo is likely just another example of the close connection between neurons in the brain and neurons in the heart. It points out the potential value of having solid and effective stress-management techniques in place and of having a good support system available in times of severe stress.

“How do dog whistles work?” asked the young man.

“They work,” replied the vet, “by emitting sounds above 20,000 Hz. Dogs can hear those sounds while people cannot.”

The vet went on to explain that the normal higher limit of adult human hearing is about 20,000 Hz (Hertz) or cycles per seconds while the lower limit is about 20 Hz.

“And a cat’s purr?” asked the young man. The vet laughed.

“Cat purrs generally fall within the range of from 20 to 50 Hz so most are within the capability of the human ear. Your dog must know the word ‘cat’ because his heart rate just increased.” The young man nodded, laughing.

“I suppose you’ve heard of infrasounds?” asked the vet. This time the young man shook his head.

Infrasounds are low-frequency sounds, lower than the normal limit of human hearing. They consist of a very long wave that goes between particles and molecules rather than bouncing off them. High-intensity infrasoundsextend in the megahertz range and well beyond but their frequency level is below 20 Hz. Sometimes you can hear part of the sound and just sense the infrasound. Sometimes you can only feel the infrasound.

“I know about them,” continued the veterinarian, “because infrasounds are prevalent among creatures in nature. Hippopotamuses, alligators, and giraffes reportedly use infrasounds to communicate over considerable distances. Sumatran Rhinoceros produce infrasounds as low as 3 Hz with similarities to the song of the humpback whale. Elephants trumpet at 15-35 Hz and as loud as 117 decibels, the sound traveling distances up to six miles. The infrasounds are used to coordinate the movement of herds and allow mating elephants to find each other. Elephants also produce infrasounds that travel through solid ground and are sensed by other herds using their feet, although the herds are separated by hundreds of miles. Elephants have bet low-frequency (infrasound) hearing than any other mammal tested so far.

“I had no idea!” exclaimed the young man. ‘”That’s absolutely fascinating. Actually, I heard a comment recently that I didn’t understand until now. Recent research by Jon Hagstrum of the US Geological Survey suggests that homing pigeons use low frequency infrasounds to navigate.”

“And then there is the roar of the tiger,” said the vet. “Tiger roars can be both heard and felt.”

The roar of a tiger contains audible sounds and infrasounds of 18 Hz and lower—which can penetrate solid objects like walls, permeate buildings, pass through mountains, and travel for miles. Its prey feels the infrasounds in addition to hearing the threatening roar—usually the last thing the victim hears—which can reach 114 decibels a few feet away (25 times as loud as a gas lawn mower). The infrasounds can paralyze its prey, which helps the tiger catch it. Sometimes the creature dies of fright before the tiger can kill it. Humans can feel the tiger’s roar, too, a sensation that can cause momentary paralysis, even in trainers who have worked with tigers for years.

Human beings react to both loud sounds and infrasounds, pouring out stress hormones that impact both brain and body in a myriad of differing ways. Physiologically, stress hormones are about survival, which always comes first. Always. Other functions take second or third place. When stress hormones are released, they shut down any function or process that is not immediately required: digestion stops, immune system function slows, libido decreases, and so on. Extreme levels of stress hormones can increase one’s risk of stroke and, in rare cases, even cause death.

Hormones are secreted all the time, dribbling out bit by bit. The body also attempts to rebalance itself all the time. Therefore it seems logical that (unless the damage is so severe it cannot be reversed) learning how to manage stressors effectively may help (at least going forward) to help the body be healthier. So will any strategy that can help the body rebalance itself easily, effectively, and accurately.

Some evidence exists that actions you take and behaviors you exhibit today can impact the immune system four to twenty-four months later. Learning to manage stressors now can positively impact your brain and body down the line. If you plan to be alive in the future, do something now that will impact your life positively up two years from now.

And remember the roar of a tiger….

If there’s a will there’s a way.

—Old English Proverb and an old Chinese Saying

“Well,” the caller said, “I got my test results back and my hormones were as unbalanced as a broken teeter-totter. I used the hormone-replacement crème for a whole month and I don’t really feel much different. Guess that was a wasted endeavor!” His voice was adamant.

I couldn’t help chuckling—to myself, of course. Hormone imbalances typically develop over time and expecting them to rebalance in a mere thirty days is often an indication of unenlightened and unrealistic expectations.

“Tell me what you know about your own pregnancy,” I said. “What were you told or what have you gleaned over the years?”

“How much time do you have?” he responded. “My mother had a horribly stressful pregnancy with me. My father didn’t want a child, at least not less than a year after their marriage, and he made no bones about telling everyone how upset he was. I guess my mother cried the whole nine months and consistently refused to consider an abortion. Good thing for me!”

What an unfortunate gestational history. In order for a person to live a healthy and productive life, hormones must be in balance. Imbalances occur when the normal rhythms of hormonal production and utilization are disrupted in order for the individual to survive. In terms of physiological importance, survival comes first. Always. Then other functions follow. When a pregnant woman is stressed, especially if she perceives a hostile environment, the fetus experiences an increased susceptibility to stress and sex hormones along with any toxins that are circulating in the mother’s body.

For a child who experienced a stressful pregnancy, he or she may require higher levels of stress just to activate the release of cortisol. Waiting to do things until the very last minute may be indicative of this. (For a female fetus, a stressful pregnancy can actually result in the child developing a more reactive brain and nervous system, which can increase her reactivity to stress over a lifetime.)

“What do you know about the first few years of your infancy and early childhood?” I asked.

“I know I had colic,” he said. “Horrible colic. Some nights I cried all night. I guess that prevented my parents from having good sleeps, which made my father even more irritable. He abandoned us when I was about seven months old.” (Colic during early infancy can be a symptom of food intolerance, which may align with hormonal imbalances.)

I explained that negative stress is cumulative; as are levels of stress hormones, such as adrenalin. When the stress hormone cortisol is high, the immune system is negatively impacted. When cortisol is too low, it interferes with the body’s ability to even mount an appropriate stress response. And when both cortisol and DHEA are low, the individual may be in a state of maladaptation or hormonal dysregulation.

At this point the caller interrupted to say that he’d been taking an oral form of testosterone but, again, hadn’t noticed much improvement.

“That may be because hormones taken orally tend to flood the brain and body,” I said. “This can trigger the body to shut down its own production of those hormones due to negative feedback related to overloading, which can result in perpetuating the imbalance rather than helping to resolve it.”

Rather than ask another question, I took a risk and just said, “According to Dr. Michael Borkin, an eminent authority on hormones, 100% of males over the age of 50 will experience some form of erectile dysfunction. It tends to be a symptom of cardio-vascular problems. Think of erectile dysfunction as the canary in the coal mine. Unfortunately, an average of eighteen months passes before the individual seeks medical assistance, by which time his hormones may be even further out of balance.”

There was a long silence on the other end of the line, broken by my saying,” Check your test print out. If progesterone levels are high, that may correlate with erectile dysfunction.”

“So how long would I need to be using these transdermal crèmes?” he asked.

“You don’t develop hormonal dysregulation in a few days or weeks,” I answered, “so it can take a long time to help the body recover and rebalance. A simple trauma, for example, can impact hormonal balance within four to twenty-four months. The effects of a traumatic fall may show up about four months later as the beginning of symptoms of dementia. It generally takes a minimum of 120 days of transdermal-crème use before any improvement is noted. And sometimes you may not have even noticed you had any symptoms because they’ve been around for such a long time you’ve become accustomed to them and assume this is just the price of being an adult in this culture.”

His next question was whether he would need to continue using transdermal crèmes for the rest of his life. “That would depend on the individual,” I replied.

Some individuals have used this strategy for several months to a year, retaken saliva tests, and been able to go on a maintenance crème with only annual retesting. Individuals who have been on such a program for the past fifteen years report they feel great and believe this strategy has helped them slow down the onset of symptoms of aging.

“Hey,” the caller said, “if that’s what it takes I’ll stop subsidizing the restaurant industry so frequently and so heavily and eat more meals at home. That’ll help pay for the testing and the crèmes.”

Good for him, I thought, as I shut off my phone. And the old proverb came to mind: If there’s a will there’s a way.