Andrea breezed into the restaurant, hung her cape on a coat peg, and slipped into a chair across from me. She had suggested lunch because, as she put it, “I want to share a success story with you.” From earlier conversations I knew that communicating with her boss had been an ongoing challenge. Six months ago Andrea had made a decision to stop overreacting during confrontations with him. As soon as the waiter took our order, Andrea launched into her story.

Starting at the beginning, she rehearsed what she had said in this latest episode, repeated what he had said, and ended by saying, “Aren’t you proud of me? When he lost his temper I just stood there calmly while he ranted and raved. I didn’t get upset, and I didn’t even cry!”

I truly wanted to be supportive, so I said, “Yes, I am proud of you. That’s a big step, learning to keep your emotions under control.” I quickly took a few sips of water, hoping to swallow my laughter. Unfortunately I lost the battle and began to chuckle. Her story was hilarious!

“Yes?” she prompted. “What’s funny?”

“Perhaps the next growth step is to explore your contribution,” I said. “Is there a chance you set up the situation so you could pat yourself on the back for not losing your cool?”

Her response was a deer-in-the-headlights expression. “Let me tell you a little story,” I suggested. “Once upon a time….”

Melissa wanted a goldfish. “Just one,” she cajoled. “I’ll take care of it all by myself and you’ll never have to do one thing!” Finally her mother agreed and they went on a shopping expedition to the pet store. After much consideration, Melissa selected a lovely little gold-orange fish, a bowl, and some accoutrements that made it look like the tiny creature was living in ancient Greco-Roman ruins. They also purchased a fish net, “so you can safely lift the fish out and put it in another bowl temporarily while you’re cleaning its home every week,” as the salesperson put it.

Melissa spent hours watching Fishetta. When it was time for the first cleaning episode, Melissa said, “I can handle it.” But she decided not to bother with the fish net. It’ll be faster if I just put my hand over the opening to the bowl and pour out the dirty water, she thought to herself. But wouldn’t you know it? That little fish squeezed right through Melissa’s little fingers and was last seen heading down the kitchen-sink drain.

“I’ve misplaced Fishetta!” Melissa shouted. And she had—permanently. Of course the little girl was devastated, and she cried and moped and moped and cried.

“Save your allowance and you can purchase another fish,” her mother suggested. “And next time, use the net.” But Melissa didn’t seem to pay much attention to that admonition. She was thinking about what she would name the next tenant.

In due time the two of them made another trip to the pet store and returned with Fishelda. When bowl-cleaning time rolled around Melissa was certain that this time she could pour out most of the water without letting the fish slip by. Oops. The little beastie got through her fingers again and disappeared down the drain. There was another round of crying and moping. Finally her mother told Melissa that she needed to stop the histrionics. “After all,” mother explained, “it was your actions that resulted in Fishelda hightailing it for parts unknown in the sewer system.” So Melissa began saving her allowance toward the purchase of Fishinna. (Melissa had no shortage of names!)

When it was time to change the water in Fishinna’s bowl, Melissa was certain she could pour out most of the water without letting the fish slip by. After all, she’d had a lot of experience. This time the little gold fish wiggled through Melissa’s fingers, took a flying fish-leap out of the sink, and landed on the floor with a plop. It flopped around, its gills working madly, as Melissa made valiant attempts to retrieve it. Mother heard the commotion and came to the rescue. She grabbed the fish net and captured the little critter but it was too late. Fishinna turned up its tiny fins and sank slowly to the bottom of the bowl.

Melissa buried the tiny fish in the back yard under a monkey-pod tree. “I didn’t cry and mope when Fishinna got away from me,” Melissa said to her mother. “Aren’t you proud of me?” Silence. “Well, aren’t you proud of me?” Melissa persisted.

“I’m glad you didn’t waste a lot of time crying and moping,” replied the mother. “However…”

“I know,” Melissa said. “If I’d used the net to begin with, I wouldn’t have lost Fishetta, Fishelda, or Fishinna.

“And wouldn’t have had anything to be upset about in the first place,” agreed her mother.

“And so,” I concluded, looking at Andrea, “Melissa brought Fishanza home from the pet store and used the net from then on.” There was no response but Andrea’s face held a puzzled look. “In metaphor,” I explained, “the story illustrates the difference between a band-aid (trying to rescue a bad situation) and a bonanza (taking preventive action that yields big dividends).”

“I understand the metaphor,” Andrea said, “but I’m not sure how it applies to me.”

I concentrated on my salad and thought: There is an ocean of difference between understanding a concept intellectually and putting yourself in the picture; in being able to stand back, as it were, and observe your own behavior to the point that you know how to alter it successfully. It’s the difference between recognizing an open door and actually walking through it. It’s all about awareness, insight, and choice.

Suddenly a knowing smile lit up Andrea’s face, and she began to chuckle. “Oh my,” she said, “I get it! I get it!” Andrea explained that her typical pattern had been to offer critical comments about projects at the end of the day, when her boss was tired and hurrying to wrap up his work. “I never could understand why he got irate and reacted negatively,” she mused. “And I was so proud of myself for not getting upset this time when he lost his temper,” she concluded. “Too funny! From now on I’ll choose a more appropriate time to offer my suggestions.”

Have any fish slipped through your fingers lately? Use the net!

It is one thing to hear generic descriptions of societal injustice; it’s another to experience this personally. And it’s quite another to come face to face with specific incidents that have happened to real flesh-and-blood people and to read, firsthand, the effect those experiences had on their lives.

Nearly one third of then nearly six hundred women who responded to my PhD dissertation project, Contemporary Women’s Issues Survey (1988 and 1990), wrote comments on the returned questionnaires. These “women pioneers,” by writing snatches of past history, speaking openly of personal experiences, and revealing glimpses of hidden pain—the impact of which is still with me years later—prepared the way for others.

NOTE: Because of the project’s specificity, all survey respondents were female. This in no way implies that males do not experience societal injustice. Sometimes the injustice is similar and sometimes it is different. Unfortunately, it seems to be part of the human experience for many. Fortunately, there have been some positive changes since the survey….

Comments, like those that follow, expressed a depth of emotion that would often leap up at me from the pages as I sat cross-legged on the floor reading the responses.

There was anger in some of the comments—at the injustice of a culture that oppresses the other half of the species “man” but it was largely unrecognized as such or disguised under feelings of frustration and futility. The women talked all around this misunderstood emotion using synonyms like resentment, pain, incense, and annoyance.

In addition, some of the women seemed confused about the difference between “caring” and “caretaking.” They seemed unclear that caretaking is doing for people what they are capable of doing for themselves. It not only wears out the caretaker and causes fatigue, resentment, and personal burnout, it also deprives others of the chance to take responsibility for their own personal growth—preventing them, in many cases, from developing, learning to take risks, and becoming actualized and differentiated. Caretaking is unhelpful to everyone involved.

For those of you who study Scripture, following are a couple of examples:

Caretaking others typically results in self-neglect, which does not help anyone in the long run because an empty cup has nothing of value to give away. Caring, on the other hand, involves healthy nurturing of self as well as others, with a goal of supporting everyone to become as actualized and differentiated as possible.

Because of my family-of-origin, I had a hard time coming to grips with anger and identifying it as a protective mechanism, a red flag to indicate something is wrong. Anger is just a signal, but a signal worth listening to. It always deserves respect and attention because it exists for a reason: to give you needed information from your subconscious mind. It may be a message that you are being hurt or violated; it may be an indication that you are being overly compromising or compliant in a relationship; it may be a warning that you are doing too much caretaking in an effort to free better about yourself—and insufficient caring; it may be evidence that an important emotional issue is not being dealt with. Like unresolved grief, unresolved anger is cumulative. Small incidents can trigger large reactions because of all the past emotion that has not been appropriately handled.

In our society, anger has been largely the province of men. It is considered “masculine” to bluster, stamp, swear, and yell. In my family it was never okay to exhibit any anger, unless you were male. Then, it was described in euphemistic terms as “righteous indignation,” or “getting your attention because you’re not listening,” or “trying to make a point,” or “saying it in a way you will remember,” or some such reason.

On the other hand, it is “feminine” to cry and to comply. Women have long been discouraged from identifying or expressing anger. The taboos have been so powerful that some women do not even know when they are angry. As a result, many women end up whining (anger squeezing out through a very small opening), developing symptoms of physical or mental illness (e.g., depression), and receiving cultural approval for burying a portion of their innate emotional self.

According to Dr. Harriet Goldhor Lerner, women today are “nothing short of pioneers in the process of personal and social change.” The challenge is for them to identify their anger, listen carefully to it, and use it constructively and appropriately in the service of change, in recognizing boundary invasions and developing functional behaviors, and in living authentically. They can still hold to what they value in female heritage and tradition. In this work of personal growth and exploration, this combination makes for the “best of pioneers.”

The downside of pioneering is that it is very hard work. It requires learning, increased awareness, personal growth, exploration, collaboration and some compromise, combined with willingness to role model standing for what works for your brain. Because of that and often due to socialized disapproval, some prefer not to do that hard work. It is, however, essential. Both males and females observe the behaviors exhibited by the generation that spawned them. You can only teach what you know. Only when larger numbers of role models are willing to be pioneers will there be hope for succeeding generations to exhibit behaviors (on a more consistent basis) that represent the authentic and appropriate use of anger.

They wrote the book Beyond the House of Silence…Secrets Layered upon Secrets—the book that changed everything for me.

It has taken five years for me to begin to come out of the “fog of my life.” I am just beginning to start over in a whole new light; a much better existence than I ever knew possible prior to reading this life-altering book. Every day thus far, without exception, some aspect, phrase, anecdote or chapter was with me for the past 1,825 days. I am remiss to have taken this long to write this because it has been on my mind ever since I opened the book. However, these authors remind the reader constantly, that the healing process “takes time” and to “be good to yourself,” something I had never practiced before—until now.

I now find reverence in onions—although peeling back each layer makes you cry and is increasingly painful—the last layer is fundamental to the structure of the whole, making is essential to the healing process. This experience feels like unraveling a colossal, knotted ball of yarn that had been neglected for years only to put it back together in an orderly way—a frustrating but necessary process of breaking things down in order to put them back together again. Anecdotal evidence shared by these two authors was the linchpin in my healing process. They courageously share in the trauma and healing of this true story, making it plausible that healing was even possible for people like myself. Without the candid experiences shared, I am not sure that I would even be present to write this—period.

I was warned about the power of this book by one of the authors—I did take heed, however, nothing could have prepared me for this experience. It was suggested that I read it slowly, however, I couldn’t put it down. I believe I read it all in one sitting and gorged upon it as it revealed things to me that I had denied for years, unknowingly. The notion of “secrecy” resonated with me. I had been in such emotional bondage for over forty years with no way out that I felt like a sinking ship—the future was inevitable until this lifeline of a book. This book scared me, haunted me, helped me, and then healed me and continues to do so along with the unprecedented dedication of my therapist Dr. Banford.

During this holiday season, it is only fitting that I thank you both, Dr. Taylor and Dr. Banford. It is a time of giving, and you both have given tirelessly of yourselves through the pages of this book. At a time when the general population is so ill-consumed with gift giving, the insanity of the consumer-driven holiday season and the quest for the perfect gift—I feel so incredibly fortunate to have been touched by your writings. It would be my hope that everyone could be as fortunate as I. To be shaped by your ideas seems essential to one’s overall wellness and happiness. Every person I know would benefit from your perspectives, and I strongly endorse this book to the overall population. Mental wellness seems like such a neglected area of medicine and the symptoms seem so pervasive in society ranging from addictions, to familial dysfunction—the list goes on. It is not hard to see the ubiquitous nature of mental illness.

Thank you for every page. I found myself on most of them…too many to possibly mention and there aren’t enough “thank yous” to go around. Alice Miller’s The Body Never Lies (p.160) reference caused me to sit and reel. Was I really picking up the check for parental emotional unfinished business? It had to be true “I was so incapacitated by the disease that I couldn’t dress…”—this entire paragraph (p. 161) was me. Could it be true? It was true—and right there in black and white before my eyes.

As a former educator of twenty years, I want to thank you both for educating me. Please continue to save lives through your research, academics, and through the giving of yourselves. I hope that you write another book together—if so, I will certainly be first in line for it. As for now, enjoy the holiday season—knowing how pivotal you have both been to patients like myself. You two truly are “gifts” exemplary of what this season should be. Merry Everything, Marilyn and Arlene!!! With So Much Love, Gratitude, and Respect…

They wrote the book Beyond the House of Silence…Secrets Layered upon Secrets—the book that changed everything for me.

It has taken five years for me to begin to come out of the “fog of my life.” I am just beginning to start over in a whole new light; a much better existence than I ever knew possible prior to reading this life-altering book. Every day thus far, without exception, some aspect, phrase, anecdote or chapter was with me for the past 1,825 days. I am remiss to have taken this long to write this because it has been on my mind ever since I opened the book. However, these authors remind the reader constantly, that the healing process “takes time” and to “be good to yourself,” something I had never practiced before—until now.

I now find reverence in onions—although peeling back each layer makes you cry and is increasingly painful—the last layer is fundamental to the structure of the whole, making is essential to the healing process. This experience feels like unraveling a colossal, knotted ball of yarn that had been neglected for years only to put it back together in an orderly way—a frustrating but necessary process of breaking things down in order to put them back together again. Anecdotal evidence shared by these two authors was the linchpin in my healing process. They courageously share in the trauma and healing of this true story, making it plausible that healing was even possible for people like myself. Without the candid experiences shared, I am not sure that I would even be present to write this—period.

I was warned about the power of this book by one of the authors—I did take heed, however, nothing could have prepared me for this experience. It was suggested that I read it slowly, however, I couldn’t put it down. I believe I read it all in one sitting and gorged upon it as it revealed things to me that I had denied for years, unknowingly. The notion of “secrecy” resonated with me. I had been in such emotional bondage for over forty years with no way out that I felt like a sinking ship—the future was inevitable until this lifeline of a book. This book scared me, haunted me, helped me, and then healed me and continues to do so along with the unprecedented dedication of my therapist Dr. Banford.

During this holiday season, it is only fitting that I thank you both, Dr. Taylor and Dr. Banford. It is a time of giving, and you both have given tirelessly of yourselves through the pages of this book. At a time when the general population is so ill-consumed with gift giving, the insanity of the consumer-driven holiday season and the quest for the perfect gift—I feel so incredibly fortunate to have been touched by your writings. It would be my hope that everyone could be as fortunate as I. To be shaped by your ideas seems essential to one’s overall wellness and happiness. Every person I know would benefit from your perspectives, and I strongly endorse this book to the overall population. Mental wellness seems like such a neglected area of medicine and the symptoms seem so pervasive in society ranging from addictions, to familial dysfunction—the list goes on. It is not hard to see the ubiquitous nature of mental illness.

Thank you for every page. I found myself on most of them…too many to possibly mention and there aren’t enough “thank yous” to go around. Alice Miller’s The Body Never Lies (p.160) reference caused me to sit and reel. Was I really picking up the check for parental emotional unfinished business? It had to be true “I was so incapacitated by the disease that I couldn’t dress…”—this entire paragraph (p. 161) was me. Could it be true? It was true—and right there in black and white before my eyes.

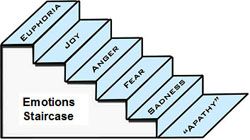

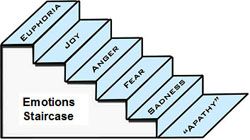

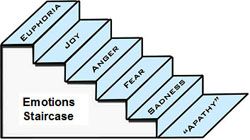

As a former educator of twenty years, I want to thank you both for educating me. Please continue to save lives through your research, academics, and through the giving of yourselves. I hope that you write another book together—if so, I will certainly be first in line for it. As for now, enjoy the holiday season—knowing how pivotal you have both been to patients like myself. You two truly are “gifts” exemplary of what this season should be. Merry Everything, Marilyn and Arlene!!! With So Much Love, Gratitude, and Respect…“I simply must find a way to teach this to my pre-schoolers!” Ellenella was enthusiastic and adamant. Curled up in front of the welcoming fireplace with its ever-changing kaleidoscope of flash and flame, we had been discussing a concept we call the “Emotions Staircase.” After having learned the concept herself, she had practicing identifying core emotions—gleaning the information each was designed to provide, taking appropriate action, and choosing which feelings to hang onto (if any). Now the woman was passionate about helping children learn similar skills “fifty years sooner than I did,” as she was wont to say.

“It does make life seem smoother,” I agreed. “No longer is one held hostage to emotions and feelings, all of which can seem frightening and powerful at the same time.” Understanding the concept of the Emotions Staircase and taking responsibility for climbing up to joy had been one of the most empowering strategies I had ever put into practice. Almost immediately half of the problems in my life had slid off the back of my metaphorical truck.

For the next hour, over popcorn and apple slices, we brainstormed. “I’ve got it!” Ellenella’s exclamation rattled the embers to say nothing of my ears. Jumping to her feet, she was on a dead run to her office. In moments she was back with cardboard, scissors, felt pen, yarn, hole-punch, and cartoon stickers. “This is what I’ll do,” she enthused, but what that meant was unclear to me.

“I’ll make a label for each core emotion,” she murmured, cutting and writing, punching holes and tying yarn. “All except for euphoria,” she went on, “because euphoria typically lasts for only a few minutes, and there won’t be any need to identify apathy—a state of being overwhelmed with emotion.” I watched, fascinated. “So all I need for each child are four labels that can be hung around the neck….”

Fast forward six months. Same welcoming fireplace, a replenished supply of popcorn and apples, and a calmly satisfied Ellenella. “It worked,” she said, simply, “and do I have a success story for you!” I refilled my bowl with popcorn and apple slices, snuggled a bit deeper into the overstuffed sectional, and prepared to listen.

Furious fuming little Farquart (as Ellenella described him) had been enrolled in her preschool at age three. Suffice it to say, his home-life was difficult. His parents, angry that they had been unable to settle their differences, had divorced. But they had continued squabbling—over everything. Little Farquart in particular. He was their bargaining chip, their emotional punching bag, and the prize whenever each parent perceived he or she was winning. No surprise, their only child was one angry little boy.

At the age of three his language abilities were insufficiently developed for him to articulate the devastation occasioned by his parents’ abject immaturity, so he had taken to acting out his frustration and insecurity by throwing things. Any object he could pick up or push might become an instant missile. Not only was this rather unsettling in the preschool environment, it was unacceptable role-modeling for the other children.

When conversations with little Farquart’s parents availed nothing (Ellenella’s words), she had decided to take him on as her first “you-can-learn-to-manage-your-feelings” project, ambitious though that was. “Of course I had 144 labels finished,” she explained, “four for each of the 36 children. But first I had to teach them about the core emotions and the information each was designed to provide.”

A contractor friend built for her a child-sized staircase with a fancy handrail. Once it was painted and installed in a corner of the school’s great room, another of Ellenella’s friends had painted a matching cartoon face on each step. Ellenella had pictures of the staircase and the cartoon faces on her computer. They were hilarious!

Ellenella began teaching the preschoolers by using words and actions. Hers. She talked about the emotion of anger when her boundaries had been invaded, as when the postal delivery van was backed into the school fence, taking down a 12-foot stretch.

Ellenella began teaching the preschoolers by using words and actions. Hers. She talked about the emotion of anger when her boundaries had been invaded, as when the postal delivery van was backed into the school fence, taking down a 12-foot stretch.

She talked about the emotion of fear when she was in danger, as when a rattlesnake had slithered onto her front porch. She spoke about the emotion of sadness when she experienced a loss, as when her little lovebird squeezed out through an opening in its cage and flew away. And she talked about the emotion of joy when life was basically going well. And when Ellenella talked about an emotion, she would stand on the matching step of the Emotions Staircase.

Gradually the children began to copy her role-modeling, running over to stand on a step while mimicking the related cartoon picture and saying “fear” or “sadness, ” and so on. That was only the first step in Ellenella’s plan, however. “I want them to be able to identify the emotion whether or not there is a real Emotions Staircase present, and to articulate the feeling they choose to hang onto.” That would be a large order for the average adult—to say nothing of a child. But Ellenella had persisted.

Little Farquart had quickly latched onto the reality of the Emotions Staircase and seemed to enjoy running over to stand on one of the steps. Before long he was able to articulate the feeling he had chosen to hang onto and did so with an almost visible sense of relief. No surprise, over time the number of items he heaved across the room or shoved across the table decreased to almost zero.

Ellenella’s success story involved a situation that had occurred at the preschool on the day of Farquart’s fifth birthday. That particular morning, when his mother dropped him off at school, she also dropped off a batch of big, luscious, homemade chocolate chip cookies—one for each child and each teacher. The cookies had been made to resemble happy faces with eyes, nose, and mouth fashioned from M&Ms. The treats were stored in the kitchen to wait until lunch. Out of sight.

As the children arrived at school, each went directly to his or her wall hook and selected a label printed with the word that described their current feeling. Most of the children would hang happy around their neck and only change the label if something happened to warrant that. Little Farquart hung the happy sign around his neck. After all, it was his fifth birthday and there were special treats for desert. It was a lovely summer’s day, so lunch was served out in the playground beneath spreading trees. When the meal was finished, the cookies were distributed.

Little Farquart, as Ellenella explained, had sat on a stump and gazed soulfully at his cookie. “Are you going to eat it?” one of the teachers asked.

“Oh, yes!” exclaimed Farquart. “But first I’m joying it.” Unfortunately, he didn’t have long to joy. Without so much as a warning bark, a huge Great Dane bounded through the open gate, neatly plucked Farquart’s big, luscious, home-made chocolate chip cookie from the boy’s hand, leaped effortlessly over the six-foot fence, and disappeared from view. There was a whole minute of stunned silence before Farquart broke it.

“Not fair! Not fair!” he screamed, jumping up and down. “That big dog stole my cookie! It’s not fair. It’s my birthday.”

“You are right, Farquart,” said Ellenella calmly. “It is not fair. That dog stole your birthday cookie.”

“Run into the school and get your labels.” The boy obeyed and returned with three labels looped over his arm. “Which one do you want to put over your happy label?” Ellenella asked.

“Anger!” shouted Farquart. “I’m mad the dog stole my cookie!” And then almost immediately he followed with, “No! I’m bad-sad. I have no cookie. Is there another cookie?”

“No,” said Ellenella, at which Farquart’s screaming and jumping became accentuated by giant sobs. Rivulets of tears coursed down his face. The five-year-old placed the bad-sad label around his neck.

“Good!” said Ellenella. “Sadness is a signal that you lost your cookie, kindness of that huge Great Dane.”

Farquart continued to cry, but the sobs were becoming less intense. He came over and stood beside Ellenella, shook his head sadly and moaned, “No more cookies.”

“There will be another time for cookies,” Ellenella said, “but you are right for now. No more cookies.” (The staff had decided in advance that they would not try to immediately replace a loss that a child had experienced but to allow the child to move through the process. So often when a loss is replaced immediately, the child fails to learn how to deal with loss successfully.)

After a few minutes, Farquart hung the Scared label around his little neck.(Ellenella had taught the children to identify the lowest step—core emotion—they were experiencing and then to walk up the staircase to joy, step by step.) “What are you scared about?” Ellenella asked the boy.

“I scared that dog’s gonna steal my cookie again!” said Farquart, emphatically.

“That is a possibility,” agreed Ellenella. “Is there anything you could do to prevent that?”

Farquart sat down cross-legged on the ground and put his chin in his hands. Finally he said, a rather sheepish grin on his little face, “I could close the gate.”

“Great idea,” said Ellenella. “However, a huge Great Dane might be able to jump the fence.”

“Well,” said little Farquart, “I could eat my cookie inside.”

“Yes,” agreed Ellenella. “Do you always want to eat indoors just because a huge Great Dane once stole a cookie from you?”

“No,” said Farquart. After a few moments he stood up, hung the mad label around his neck and began jumping up and down again. “I’m really MAD,” shouted little Farquart. “It wasn’t fair!”

“Unfortunately,” said Ellenella, her voice sympathetic, “life isn’t always fair.” She watched Farquart jump up while yelling “Not fair, not fair!” After a few moments she asked, “How long do you want to stay mad?”

“Two minutes!” shouted little Farquart. Ellenella smiled and looked at her wrist watch. The child continued to jump and yell for about twenty seconds. Suddenly he stopped and said, “How much time?”

“You’ve been yelling and jumping for twenty seconds,” Ellenella answered, patiently. For a moment it looked as if Farquart might continue his mad antics, but almost as suddenly as he had started, he stopped.

“Done,” said little Farquart. “Two minutes is a long time.”

“Are you ready to put on your happy label?” asked Ellenella? “Think of one thing that you learned and that could make you happy.”

Once again Farquart assumed a thinker pose. Finally he said, “I’m happy the dog didn’t bite me.”

“Excellent,” said his teacher. “Anything else?”

“I’m just happy,” said the little boy. “I’m tired of being mad.” So saying, he hung the happy label around his neck. He removed the other three labels and went into the school to hang them on his hook.

When little Farquart returned to the playground, one of the other teachers said, “Farquart, I am going to share my cookie with you.”

“Are you giving me your cookie?” His little eyes sparkled with joy and hope.

“I am sharing my cookie with you,” the teacher responded and handed him half her cookie.

At this, little Farquart began to jump up and down again. His little face was wreathed in smiles and the gap occasioned by a missing tooth showed clearly. “What do you say?” prompted Ellenella.

“I say Gracias!” shouted Farquart, using one of his new words. “I say Gracias, Gracias!” The teachers smiled as Farquart continued, “I’m BIG JOYING!” He ran off to join his friends, nibbling his cookie with obvious pleasure.

“That,” Ellenella told me, a contented smile on her face, “is a major success story! If a child can learn to do this, anyone can!”

She was right.

Note: Additional information on Emotions and Feelings and on Emotional Intelligence may be found in Brain References.

“That does it!” Jake was in full roar. Amy had failed to stop for gas on her way home. Admittedly that was unhelpful. But so was Jake’s ranting, raving, and flailing of long arms that put at risk within reaching distance. Nancy placed her hands over her ears and burst into tears. This too was unhelpful but it was part of their typical pattern. Jake would get frustrated and exercise his lungs; Nancy would get flustered and exercise her tear ducts.

“Heaven to help us!” exclaimed great Uncle Herman, still spry at 87. “The car it needs some gas. So, fill ‘er up!”

“Amy should have!” Jake bellowed.

“So, send her now,” great Uncle Herman said and added, “She’s seventeen? Maybe still some child. She’ll learn.” Silence. He turned to Nancy. “So, this is so bad you have tears?”

“When Jake yells I cry….” Nancy’s voice trailed off.

“So, he makes the huge noise like a bull elephant and you cry! Your eyes they are connected to your ears or vhat?” Great Uncle Herman raised an eyebrow and a shoulder.

“I don’t have time for this nonsense,” Jake began.

“Nonsense for sure,” great Uncle Herman agreed, interrupting. “So, you vant to spend your energy in tears?” He looked at Nancy who was wiping her eyes. “So, you vant to spend your energy in loud?” He looked at Jake who looked a trifle uncertain, opened his mouth, and shut it again. “Look at your vatch, man,” great Uncle Herman directed. “Pick some time. How long you vant to waste on the angry?”

Jake looked at Amy, then at Nancy, and finally at his Rolex. “Two minutes,” he replied after a pregnant pause. He was actually starting to feel a bit foolish. The situation seemed both ludicrous and ridiculous and he was having difficulty keeping his face straight.

“So, be you livid for two minutes,” ordered great Uncle Herman. “Go outside. Valk. Den Amy to get gas!” He turned to leave the room, shaking his head and muttering, “Big vaste of energy all dat yelling and crying!”

Great Uncle Herman was right. Many people expend vast amounts of energy yelling and crying, often over a little blip on the screen of life. When negative behavioral patterns continue year after year, I picture those individuals as suffering from The Ostrich Syndrome, their heads stuck in the proverbial sand box, at least in terms of managing their emotions and feelings.

Not only do human beings vary tremendously in their perception of emotions but also in their ability to identify, articulate, and manage them effectively—a challenge that ranks right up there in everyday living. A first step is figuring out the difference between emotions and feelings. Although these words are frequently used interchangeably, they are not synonyms in terms of brain-function. Emotions and feelings even follow different pathways in the human brain!

Emotions are physiological changes that occur in response to an external or internal stimulus (e.g., a thought). They function as cellular signals designed to get one’s attention much as an orange highway flag is designed to alert a driver to a situation up ahead. When in the grip of a strong emotion the human brain is in a biochemically-altered state that comes complete with typical facial expressions, physiological markers, gestures, and actions. Candace Pert, the researcher who first identified opiate receptors in the human brain and who was interviewed in the documentary “What the Bleep?” believes that each core emotion may even be connected with a specific neuropeptide (brain chemical).

Although beliefs differ regarding the number of core emotions, scientific evidence exists that facial expressions registering at least joy, anger, fear, and sadness are inborn and can be observed on the face of a fetus during gestation. Emotions translate information from the subconscious into conscious awareness and provide energy for constructive action. In this sense all emotions are positive, although the actions exhibited around them may be negative.

Feelings, on the other hand, reflect one’s subjective interpretation as the brain tries to make sense of the physiological changes that resulted from the emotion. Human beings create their own feelings based on past experience, learned behaviors, personal belief systems, and thought patterns to name just a few. It’s empowering to realize that no one can force you to maintain a specific feeling over time. Others can provide a stimulus that triggers an emotion but you take it from there in terms of feelings and behaviors.

This means that while you may not be responsible for every emotion that surfaces, generally you are responsible for the feelings you choose to maintain—because your brain created them—and the behaviors you choose to exhibit (e.g., there may be cases of neurochemical imbalances that impact free will).

Table 1: Following is a list of core emotions, along with a summary of their purpose, and examples of undesirable outcomes that can result from mismanagement.

| Core Emotion | Outcome of Mismanagement |

| Euphoria (awe, elation, bliss) – a signal that something very rewarding or pleasurable is happening. It provides energy to experience special moments that can add spice and excitement to your life. | Euphoria – unmanaged it can prompt you to search for activities that provide a continual high, through direct or indirect self-medication that alters your neurochemistry (e.g., addictive behaviors). |

| Joy (happiness, enthusiasm, general contentment) – a signal that all is going well in your life. It is a natural state of anti-depression hardwired into the brain. It provides energy to live life in all its fullness—balanced, contented, and productive. | Pseudo joy – false joy can lead to obsessions/compulsions, addictive behaviors, a sense of unreality, frustration, and depression. |

| Anger – a signal that your boundaries have been breeched (e.g., physical, mental, emotional, sexual, spiritual). It provides energy to create and implement bona fide boundaries. Without anger you may lack the motivation to take corrective action or begin to tolerate the intolerable. | Anger – unmanaged it can lead to bitterness, illness, injury, and death. Anyone can become angry; that is easy. But to be angry with the right person, to the right degree, at the right time, for the right purpose, and in the right way, this is not easy. —Aristotle In your anger do not sin; do not let the sun go down while you are still angry. —Ephesians 5:26 NIV |

| Fear – a signal of danger. It provides energy to take appropriate protective action. Without fear you may be unable to protect yourself adequately. | Fear – unmanaged it can kill your ideas, undermine confidence, and escalate into phobias and/or immobilization. |

| Sadness – a signal that you have experienced a loss. It provides energy to grieve losses, heal past woundedness, and recover. Without sadness you may be unable to grieve successfully. | Sadness – unmanaged it can lead to immune system suppression, depression, and/or immobility (even apathy). |

Rather than being labeled as core emotions, surprise, disgust, shame, and guilt are often referred to differently. Surprise and disgust are emotional motivators that can arise in combination with a core emotion. Surprise can surface in combination with any core emotion, disgust often in combination with anger, fear, sadness, or sadness.

Shame and guilt are learned reactions that serve as interrupters to remind us of our human limitations. It can be difficult to differentiate between the two. Healthy shame says, Oops, I made a mistake! I can learn a more functional behavior, and make a different choice in the future. Healthy guilt can motivate toward constructive action when one has violated personal values or standards. Contrition is another term that is sometimes used as a synonym for healthy guilt. Contrition involves some remorse for having made a mistake along with some responsibility for the mistake or at least for one’s part in the situation. Neither healthy guilt nor contrition beats one up endlessly for being human.

False shame says, What a putz! You are so inadequate. You deserve to be punished. You have no right to express any emotion the other person doesn’t like. False guilt is a sense that you yourself are a mistake, rather than you simply made a mistake because of being human.

The Emotions Staircase portrays core emotions as a series of steps. I have found this model exceedingly helpful. You will be metaphorically standing on one of the steps at any given moment. With increased awareness of my own emotions and strategies for managing them more effectively, I now spend most of my time on the step of joy and typically move to another step only when the present situation warrants it (refer to Table 1). And where it used to take days or months to resolve anger, fear, or sadness, I can walk back up the stairs to joy in a matter of minutes or hours.

The Emotions Staircase portrays core emotions as a series of steps. I have found this model exceedingly helpful. You will be metaphorically standing on one of the steps at any given moment. With increased awareness of my own emotions and strategies for managing them more effectively, I now spend most of my time on the step of joy and typically move to another step only when the present situation warrants it (refer to Table 1). And where it used to take days or months to resolve anger, fear, or sadness, I can walk back up the stairs to joy in a matter of minutes or hours.

NOTE: While not thought to be an emotion in and of itself, apathy may represent a state of emotional overwhelm in which the individual becomes immobile. Human beings rarely try to commit suicide when they are in a state of apathy. They don’t have the energy! They can be at higher risk for suicide attempts, as they begin to move back up the emotional tone scale and get more energy.

Here is an example of how I use the emotional tone scale model to help me avoid taking things personally or becoming defensive. Imagine that a seminar participant comes up to me at a break and says, “The clothes you’re wearing don’t suit you.” Immediately I brainstorm possible reasons for the comment. Since thoughts can fly across neuron pathways at rates of 400 feet per second, this happens almost instantly:

If I want to know more about that brain’s opinion I can say, “Please be more specific.” If not, I can ignore the statement or say, “Thank you for sharing your opinion,” and move on to another topic.

At my first opportunity, I will take a brief inventory. If there has been no negative impact to my brain, I remain at a position of joy, understanding that the unsolicited opinion reflects that brain’s perception only, and may have little, if anything, to do with my reality and the way my brain perceives.

If my brief inventory reveals that I am no longer at a position of joy, that this comment did impact my brain negatively, then I need to take conscious action to resolve that negative impact—since every thought I think affects every cell in my body. This is the typical self-talk process I would use to process that comment and mentally reposition myself at joy on the metaphorical Emotional Tone Scale:

Obviously it takes much longer to write this all down compared to the relatively short time it requires to go through the self-talk process. You need to develop your own style, recognizing that you can’t skip any steps on the return to joy. Metaphorically you pass through them going both ways, but during the actual event everything usually happens so quickly that you aren’t aware of this. Your goal is to move to the step that is appropriate for the situation at hand, and then take the necessary steps to return to a position of joy.

Managing emotions optimally is a learned skill. Many didn’t learn that skill growing up because their care-providers didn’t possess the skill. After all, human beings can only share what they know. Children learn their first skills by observing caregivers and role models. If yours were highly functional in terms of managing their emotions, you may have gotten a jump-start on the process. If that was not the case, there is reparenting work to do!

PET Scan studies have shown that the left frontal lobe of the brain is activated when the research participant is experiencing joy. Since the function of will power may be managed in that area of the brain, as well, this suggests that it is possible to choose to live joyfully, to use will power to experience contentment in times of distress, and to find the silver lining in times of crisis. Epictetus, a 7th Century philosopher, reportedly believed that only 20% of the effect to one’s mind/body is due to any given event, while 80% of the effect results from the way in which the individual responded to the event(s).

You are in a much better position to make conscious choices about the way in which you want to manage your emotions and feelings, the actions you decide to take, and the behaviors you choose to exhibit when you:

You can learn to identify your emotions accurately, recognize the information they provide, and take responsibility for the feelings you maintain and the actions you take related to them (sometimes the appropriate action is to do nothing). You can hone the skill of processing an event with an emotional component (especially one that involves an overreaction) quickly and consciously. As your skill level increases and you learn to talk yourself through the process of living joyfully, you can role model for others and even teach the strategies to young children. What a deal!

Feeling always follow thoughts;

to change the way you feel,

change the way you think.

—Wayne Dyer PhD

“I’ve heard that emotions are different from feelings,” said the high school teacher, “although I’m a bit fuzzy on the details. And intellectually I know that my brain creates my feelings as it tries to interpret the reason for the emotion and its meaning.”

Jerod paused, folding his lanky frame into a nearby chair.

“What I struggle with is how to change my feelings and get myself back to happiness in a timely manner.”

“Welcome to the human race,” I said, smiling. “The bottom line is that you change the way you think to change the way you feel, as feelings always follow thoughts. It’s a learned skill.”

In their 2011 book, Joint Custody with a Jerk: Raising a Child with an Uncooperative Ex, the authors point out that when you understand that your feelings are triggered by what you think about an event and not by the event itself, you gain a measure of control. You can change your thoughts, and a change in thoughts often radically alters your feelings. This can alter the behaviors you choose to exhibit, as well, because behaviors always follow thoughts.

“Remind me of the differences between emotions and feelings,” Jerod said.

I summarized the research this way.

According to Candace Pert, PhD (the INH researcher who first identified opiate receptors in the human brain and who was interviewed in the documentary “What the Bleep…”), emotions give you information. Each emotion may be connected to a specific neuropeptide, i.e., a neurotransmitter than impacts mood. Molecules of emotion arise in the brain and body in response to something in your internal environment or external environments, creating physiological changes. Think of these as cellular signals designed to get your attention much as an orange highway flag is designed to alert a driver to a potentially dangerous situation up ahead. Although beliefs differ regarding the number of core emotions, scientific evidence exists that facial expressions registering emotions such as joy, anger, fear, and sadness (at the minimum) are inborn and can be observed on the face of a fetus during gestation.

When in the grip of a strong emotion, you are in a biochemically-altered state that comes complete with typical facial expressions, physiological markers, gestures, and actions. Emotions translate information from the subconscious into conscious awareness and provide energy for constructive action. In this sense all emotions are positive, although the actions exhibited around them may be negative.

In contrast, the term feelings is the label for your brain’s personal interpretation as it tries to make sense of the physiological changes resulting from the emotion. You create your own feelings based on past experience, learned behaviors, expectations, personal belief systems, and thought patterns, to name just a few. This means that while you may not be responsible for every emotion that surfaces, generally you are responsible for the feelings you choose to maintain—because your brain created them.

A mood is simply a feeling that hangs around for a long time. You also choose the behaviors you will exhibit related to your feelings, although it is recognized that there may be cases of neurochemical imbalances that impact free will.

It’s empowering to realize that no one can force you to maintain a specific feeling over time. Others might provide a stimulus that triggers an emotion, but you take it from there in terms of feelings and behaviors.

Jerod nodded and said, “Right. Now remind me of the Emotions Staircase. I’ve heard you mention it.”

He was referring to a model that portrays emotions as a series of steps, a model that many have found exceedingly helpful. At any given moment, think of yourself as standing on one of the steps. You decide if you will stay on that step or move to a different step.

While not thought to be an emotion in and of itself, apathy may represent a state of emotional overwhelm in which the individual becomes immobile. Human beings rarely try to commit suicide when in a state of apathy—they don’t have the energy! They can be at higher risk for suicide attempts, as they begin to move back up the Emotions Staircase and get more energy.

I laughed. “Well, I’ve been working on honing those skills for some time now, although there’s always more to learn. With an increased awareness of my own emotions and strategies for managing them more effectively, I now spend most of my time on the step of joy and typically move to another step only when the present situation warrants it or an emotion triggers a move. Where it used to take days or months to resolve the protective emotions of anger, fear, or sadness, I usually now can walk back up the stairs to joy in a matter of minutes or hours.” It was my turn to pause. “When something egregious happens, it might take a day or two or even three, but rarely longer than that.”“I take it you’ve learned how to do this,” said Jerod. “That’s the reason I’m here talking to you.”

“I don’t see shame or guilt on the Emotions Staircase,” said Jerod.

“I don’t see shame or guilt on the Emotions Staircase,” said Jerod.

He was right. Rather than being labeled as core emotions, shame and guilt (along with surprise and disgust) are often referred to as motivators and interrupters. Surprise and disgust are considered emotional motivators that can arise in combination with a core emotion. Surprise can surface in combination with any core emotion, disgust often in combination with the three protective emotions, anger, fear, and sadness.

Shame and guilt are learned reactions that serve as interrupters to remind us of our human limitations. It can be difficult to differentiate between the two:

Healthy guilt can motivate toward constructive action when one has violated personal values or standards. Contrition is another term sometimes used as a synonym for healthy guilt, signifying some remorse for having made a mistake along with some responsibility for the mistake or at least acknowledging one’s part in the situation. Neither healthy guilt nor contrition beats one up endlessly for being human. Falseguilt is a sense that you yourself are a mistake, rather than you simply made a mistake because of being human.

“Got it,” said Jerod. “Please give me an example of how you walk up the Emotions Staircase.”

I use the Emotions Staircase model to help me avoid taking things personally or becoming defensive. Imagine that a seminar participant comes up to me at a break and says, “The clothes you’re wearing don’t suit you.” Immediately I brainstorm possible reasons for the comment. Since thoughts can fly across neuron pathways at rates of 400 feet per second, which is about 200 miles per hour, this happens almost instantly.

I might think:

If I want to know more about that brain’s opinion, I can say, “Please be more specific.” If not, I can ignore the statement or say, “Thank you for sharing your opinion,” and move on to another topic.

Today, an unsolicited comment like that would likely not move me off the step of joy because I’m clear that it reflectsthat brain’s opinion—and is really none of my business—and may have little (if anything) to do with my reality and my brain’s opinion and perception. I mean, really, would anyone suppose that I would choose to lecture in clothing that I thought did not suit me?

For purposes of discussion, however, let’s imagine that this comment has a negative impact on my brain. I need to take conscious action to resolve that negative impact, since every thought and feeling impacts every cell in my body. The following illustrates my typical self-talk strategy to process such a comment and mentally reposition myself at joy on the metaphorical Emotions Staircase:

At sadness. That’s appropriate to the sense of “loss” at failing to make a good impression on this participant.

My brain connects that comment to an event during childhood when I was wearing a homemade, rather shapeless, flour-sack dress. I had felt inadequate, self-conscious, and ashamed of my appearance compared to some of the other children. Some old self-esteem issues surface that prompt me to wonder if I even know what looks good on me (my sensory preference is auditory; visual, my lowest). Also, remnants of unrealistic expectations exist that say, if I try hard enough, I can make a positive impression on everyone.

Not this time. That brain’s opinion is none of my business unless I choose to take it personally. And I don’t. I like what I’m wearing, and it’s both appropriate and comfortable. I take a deep breath and, using the energy generated by the emotion of sadness, move to the step of fear.

Perhaps fear that at another time some individual will make a similar comment, my brain will connect it to past experiences, and I’ll sense discomfort again. I can’t guarantee that won’t happen. However, I remind myself that I am an adult, I can take care of myself, and I know how to implement appropriate boundaries. I take a deep breath and, using the energy generated by the emotion of fear, move to the step of anger.

That someone (who didn’t exactly look like the cat’s meow to me) had made a judgment about what I wore! What flaming nerve! I can’t be accountable for another brain’s perception or criticism. I remind myself that each brain is different and actually start chuckling at the audacity. I take a deep breath and, using the energy generated by the emotion of anger, step up to joy.

There is always at least one:

“But you need to develop your own style,” I told Jerod. “Recognize metaphorically that you cannot skip steps. You walk up and down on each depending on where you land, but during the actual event everything usually happens so quickly that you aren’t aware of this. Your goal is to move to the step that is appropriate for the situation at hand, and then return to a position of joy as soon as possible. As you gain skills, you can move along the staircase quite quickly and successfully.”

“As you gain skills…,” Jerod repeated, unfolding himself from the chair. “That’s the key, and I have a sense that I’ll get some practice honing those skills in class this afternoon. Thanks.” And all seven feet of himself disappeared through the open door.

Managing emotions and feelings optimally is a learned skill. During the growing-up years, many didn’t learn that skill because care-providers didn’t possess the skill themselves. After all, human beings can only teach what they know.

Children learn their first skills by observing caregivers and role models. If yours were highly functional in terms of emotional intelligence, you may have gotten a jump-start on the process. (At least you had the opportunity to watch effective role modeling.) If that was not the case, you may have work to do, developing and honing requisite skills.

I was sure Jarod would gain the skills—because he had decided to do so.