How Do You Say "No"?

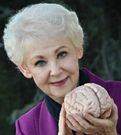

©Arlene R. Taylor PhD www.arlenetaylor.org

Wielded wisely, “no” is an instrument of integrity and a shield against exploitation. It often takes courage to say. It is hard to receive. But setting limits sets us free.

—Judith Sills, PhD

“If I ever say ‘no’ to my family or friends, they complain I’m selfish or have a negative attitude or am not being nice or don’t know how to be a team player. My brother says ‘no’ all the time—at least it feels that way—and most of the time they just say ‘okay.’ It’s not fair!”

“If I ever say ‘no’ to my family or friends, they complain I’m selfish or have a negative attitude or am not being nice or don’t know how to be a team player. My brother says ‘no’ all the time—at least it feels that way—and most of the time they just say ‘okay.’ It’s not fair!”

Clara, it turned out, was twenty-three and, as far back as she could recall, “no” from her was an unacceptable response. Even during the so-called terrible twos, when children begin to differentiate themselves from other human beings—likely by saying “no” because there is usually little opportunity for saying “yes”—Clara had been expected to do as she was told and be quick about it.

Used appropriately, saying “no” means something. It is a clear statement that you, as a separate and unique individual, have personal limits, e.g., ethical, social, spiritual, sexual, financial, physical, mental, emotional, and professional. These boundaries help you connect with others and stay safe at the same time. When you say “no,” it affirms your personal limits clearly and positively. In one setting it may announce your integrity while in another it may shield you from being exploited. If you can never say “no” to anything, you are being controlled possibly by expectations, family scripts, and/or perceived rules or threats—whether verbalized or not.

“Growing up there was always only one option,” said Clara, “and I was expected to be agreeable and immediately acquiesce. I didn’t have any other choice.”

I wanted to respond empathetically. “I regret that you had few opportunities to practice making choices.”

The words options and choices clearly imply decision-making, a key developmental task that underlies much of a person’s success in life. The wise parent or care provider offers children choices very early in life and as often as possible. Giving only two choices at a time is preferred, since the brain has only two cerebral hemispheres. Almost any two choices work if they are safe and healthy. This gives the child practice at making choices by saying “no” to one and “yes” to the other.”

For example:

- Pick either the red top or the blue top. Your choice.

- Would you like me to cut your potato, or will you do it yourself? You choose.

- I have water and orange juice. You may choose either one.

- This morning you can play kickball or climb on the jungle gym.

When the child makes a choice, make sure to follow that choice so he or she learns that there are consequences to making choices. Sometimes a child who wants desperately to please or who has learned it is unsafe to verbalize personal wishes will say, “I don’t care. You choose.” That’s a great opportunity to reply with: ‘You are the only person who will be with you for your entire life. It’s important that you learn to take good care of yourself by knowing how to make choices. You are old enough to start now.”

Make no mistake. It takes courage to offer choices, especially in the short term. An anxious, over-controlling, or perfectionistic adult, or a care provider with self-esteem issues, is typically too fearful to encourage a child to make choices. At times it may be faster and easier to just tell the child what to do. This is unhelpful in the long term, however. The healthy, functional adult or care provider, one with a balanced sense of self-worth and high levels of emotional intelligence (EQ) understands the critical importance of each human being learning to make choices and experience the consequences of those choices. Generally they provide this opportunity on a regular basis. And the sooner in life the better.

Negativity is as different from a healthy and functional ability to say “no” as night from day. Negativity is an undesirable mindset. Think of it as a whining approach to life, a way to avoid making a decision and then complaining about the outcome. Negativity looks for what is undesirable or focuses on what did not or cannot happen. Sometimes it reflects the person’s attempt to feel better about himself or herself by finding fault with the environment or with the behavior of others. It will sap your energy, diminish the enthusiasm of others, and pretty much ensure that you will not be pleased.

“When someone says ‘no’ to you,” I asked Clara, “what do you think?”

“I think, I wish I could say that,” said Clara. “I think, it must feel wonderful to have a choice.”

“You have the power to say ‘no,” I replied. “It appears to be built into every human brain. Many people relinquish their power to others, however. Individuals (females especially) often are controlled in the name of love. The more they want love, the more likely they are to give up their power of ‘no.’ My brain’s opinion is that in adulthood you can never genuinely say ‘yes’ unless and until you can appropriately say ‘no.’”

Clara really started to open up. “Most of my life I’ve felt like a puppet on a string. The string may have been invisible, but it was there. When I said ‘yes’ everyone was happy; if I ever tried to say ‘no’ all hell broke loose. Now I can never say ‘no.’ What’s wrong with me?”

“Children often perceive themselves as little giants, powerful enough to make everyone around them either happy or mad. In adulthood, think of the ability to say ‘no’ as a metaphorical insurance policy,” I suggested. “Prevention and pre-planning are usually so much better than cure.”

“I want to take back my power of ‘no,’ but have no idea where to start,” said Clara.

“Start by practicing with yourself,” I replied. “Use the language with yourself.”

“Practicing?” asked Clara. “How do I practice saying ‘no’?”

“Let’s begin now,” I said. “I will give you some simple options and you answer ‘no’ to one and ‘yes’ to the other—or ‘no’ to both, as the case may be. Here we go. Would you like a glass of water or some hot herb tea?”

“I’m fine,” said Clara.

“I know you are fine,” I said. “The issue is to practice making a choice and using the language. You can do this.”

Suddenly Clara laughed. A hearty, mirthful laugh. “In that case,” she said, “my answer is no to the water and no to the tea. I’m not thirsty.”

“Good girl,” I said. “Do you perceive any difference between saying I’m fine and no?”

Clara nodded. “Saying that I’m fine isn’t really answering the question.” Now it was my turn to nod.

“Begin at home around the house or when grocery shopping. Think two options at a time and create opportunities to practice. Whenever you have a decision to make, ask yourself this: ‘Clara, do you want to wear blue jeans or slacks? Do you want asparagus or broccoli’? Give yourself two options and then answer ‘no’ to one and ‘yes’ to the other. Practice, practice, practice!”

“I can to this,” Clara said. “I can make a game of it.”

“The more fun you have, the better. With time, you’ll become more comfortable using the language with yourself. The next step is using it appropriately with others.”

“How do you say no?” asked Clara. “There must be tons of requests you cannot meet.”

“You are correct,” I said. “If I acquiesced to all requests, I would fail to accomplish my own life goals. When the answer needs to be ‘no,’ I try to deliver it in the way I would want to receive it.”

“People always act hurt or angry when I say no,” said Clara.

I nodded. “Most brains want a ‘yes’ rather than a ‘no,’ so they can have difficulty hearing a ‘no.’ And if the individual perceives he or she is valuable only when others acquiesce, it can be downright uncomfortable. Sometimes I can respond without using the actual word ‘no’ and add it only if my answer appeared not to be heard, understood, or accepted.”

“But how do you say no?” Clara repeated.

“There are several strategies I’ve honed over the years,” I replied. “It began with a clarity that I will be with me for my entire life. As my own best friend, I choose to make optimum, healthy choices for my brain and body.”

Clearly, Clara needed some examples, so I offered several from my own experiences.

Request: “We’d like to take you to dinner tonight.”

Answer: “Thank you for the invitation. It’s very kind of you. Since I speak again first thing tomorrow morning, however, I need to call it a day right after my last lecture.”

“But what if they coax or say it can be an early dinner or come up with lots of reasons that sound good at the moment or pout?” asked Clara.

“In that case I’ll usually say that I’ll let them know later in the day. This gives me time to think things through, monitor my energy levels, evaluate whether or not I really want to accept, and if so, whether I can go and still keep my life in balance. If I still choose to decline, I just repeat my earlier response. If they keeping pushing, I’ll say calmly and firmly, ‘No, thank you.’ A ‘no’ that follows some thoughtful decision-making is far better in the long term than an emotionally impulsive ‘yes’ that you end up either regretting or having to retract.”

Request: “We’re going to the beach tomorrow, and we’d like you to go with us.”

Answer: “Thank you for wanting to include me. I must decline as going to the beach does not work with the type of skin I have and my history of skin cancer.”

“You’d really tell them you’ve have skin cancer?” asked Clara.

“I divulge personal information judiciously, when I am comfortable doing so and believe it will help others better understand my response. Someone with my type of fair skin is doing the smart thing to avoid baking on the beach, especially when he or she already has had a skin cancer due to sun damage.”

Request: “I’m going bowling tonight. Do you want to come with me?”

Answer: “Thank you. I already have an appointment so will be unable to accept your invitation. I think it would have been fun. Have a great time.” I paused. “If it’s something I’d really like to do, I can negotiate. ‘Tonight is out but Wednesday or Thursday nights are open if either of those works with your schedule.’ Sometimes it does and sometimes it doesn’t.”

“But what if I don’t have an appointment,” said Clara. “Then what?”

“Create a standing appointment with yourself,” I said. “Write it on your calendar each day. You have the option to set it aside if you decide on a different course of action, but it’s always there should you need it.

“Oh, my goodness!” Clara exclaimed. “That’s wonderful! No one ever told me I could have a standing appointment with myself. But who better? I like the thought that I’m the only person who will be with me for my entire life! But what if they won’t take no for an answer?”

“Sometimes people keep pushing for what they want, that’s true,” I replied. “Especially when they have poor personal boundaries themselves or self-esteem issues. If they suggest that you should change your schedule, a simple ‘no’ is sufficient. If they want you to disclose all the details and reasons, I simply repeat calmly that I already have an appointment. My father once told me: ‘Unless you are being cross-examined in court, you do not have to answer every question you’re asked simply because someone asked it. Live the 11th commandment,’ he would say. ‘Thou shalt not explain.’ Of course, the first time I used that with him, my father said that while he wanted me to learn the strategy I was only to apply it (to him) after I’d grown up and left home.”

Clara laughed. “I think I’d have liked your father!”

It’s a continual balancing act: evaluating, making choices, following through on my decisions, being able to negotiate, being willing and able to alter my decision if that appears to be the wiser course, and sometimes just agreeing to disagree. There are times when I absolutely must take care of myself and my schedule in order to accomplish my personal goals. At other times I might prefer a quiet afternoon at home but my concern for others outweighs that desire. For example, I might choose to read to a vision-impaired shut-in, donate a couple of hours to present anti-aging strategies at a retirement center, help a friend move, fix dinner and take it to a family who has just brought their child home from the hospital or who has suffered a bereavement. Maturity, for me, involves being able to find my voice to say “no” as well as “yes.”

Do you ever say “no”?

If your answer is “no,” you might want to reconsider. Plan head, practice, and then remind yourself often that “no” is a legitimate response. In some situations, it can be life-saving. And, as my father said, not offering an explanation can be all right, too!