Stop at the Curb!

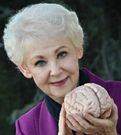

©Arlene R. Taylor PhD www.arlenetaylor.org

Eloise steered her faithful Toyota to a spot across from the sturdy farmhouse and parked under the branches of a huge live oak. Hardly had the engine died when the front door of the house burst open and Amy exploded out onto the front porch. With a shout of delight, the little girl began running toward the car.

Eloise steered her faithful Toyota to a spot across from the sturdy farmhouse and parked under the branches of a huge live oak. Hardly had the engine died when the front door of the house burst open and Amy exploded out onto the front porch. With a shout of delight, the little girl began running toward the car.

Jason’s tall frame filled the doorway. “Stop at the curb, Amy,” said her father. “Stop at the curb.” Five-year-old Amy skidded to a stop at the curb, the toes of her little shoes hanging over the edge.

“Hurry Grami!” she shouted. “Hurry!” Eloise hurried. Crossing the street she held out her arms and precious little Amy leaped into them. How different this was from her last visit. It was all Eloise could do to restrain tears of joy. Her son, her Jason had gotten it!

“How you’ve grown, Amy!” Eloise said. “It’s been three months since I was here and I think you’ve grown three inches!” Amy giggled.

“Amy’s been watching at the window for hours,” called Becky from the front door. “Come on it and unwind from your trip!”

When Eloise had last visited, Amy had been watching at the front window, as well. Over and over the little girl had asked her parents, “When will Grami get here?” And when the car had come into view and Amy had flown out the front door to greet her beloved Grami, the little girl had not stopped at the curb. Instead, Amy had run out into the street and only the quick-witted maneuvering on the part of the alert taxi driver had avoided a horrible accident. Unfortunately, a great many tears and recriminations had followed.

“How many times have I said Don’t run out into the street?” shouted her father. “How many times?”

“I don’t know,” said Amy.

“You could have been killed!” exclaimed her mother. “What’s the matter with you, scaring me like that?”

Again, Amy didn’t know.

What with the shouting and emotions and tears and unanswerable questions, Grami’s arrival had turned into a proverbial disaster. After the dust had settled and Amy’s little face had been washed and dried, it was time for dinner. Becky had ladled her delicious split-pea soup into home-made bread bowls, but no one had seemed very hungry. Conversation had been desultory and thoughts of the near-disaster had to hang over the table.

After Amy’s bedtime-story reading had been completed and the dear little girl had been tucked into bed, the three adults had settled themselves around the fireplace. That was when Grami had decided to offer a “generational apology,” as she termed it.

“Jason,” Eloise began, “I’d like to apologize for all the times I told you growing up what not to do instead of telling you what to do. I would have done better if I had known to do better.”

“Aw, Mom,” her son said, “It’s okay. I know you did your best.”

Eloise twisted her face into a wry grin. “Thanks, son,” she said. “I appreciate your generosity. However, I wish some of this new brain-function information had been available back then. It could have made all our lives easier.”

“How could it have made your lives easier?” asked Becky, leaning forward in her chair. Smiling, Eloise had given her explanation.

The brain thinks in pictures. When you tell people what you want them to do, you create the picture you hope their brain will follow. For example, the words Keep your hand away from the hot stove hopefully create a picture in the brain of a stove with the person’s hand held away from the hot surface. It’s a one-step process. What you see is what you are supposed to do.

Telling people what you do not want them to do (e.g., don’t touch the hot stove) requires a two-step process. First the brain creates a picture of touching the hot stove. Then it tries to create the reverse of that picture because that’s whatdon’t means. The brain may fail to reverse the picture successfully, however, or fail to do so in time to avoid getting burned.

“For as far back as I can remember,” Eloise told the young couple, “my parents said don’t get married before you graduate.” Her brain had created a picture of a wedding first and then a graduation. “My brain must have missed the don’t,” said Eloise smiling, “because I got married when I was 19—and then graduated two years later.”

“And I was your graduation present,” Jason said, laughing.

“The best one I got!” said Eloise.

“Oh,” said Becky, joining in. “If your parents had said graduate before you get married, the picture would have been graduation first and then a wedding.”

“Exactly!” said Grami, smiling. “Telling the brain what you want creates a one-step picture that gives the brain a map to follow. Telling the brain what you donot want, requires a two-step picture, which the brain may or may not reverse effectively. Of course, there is no guarantee that the person will follow the one-step picture. But at least the failure to reverse the original picture is minimized.”

“So when I told Amy not to run into the street,” Jason said reflectively, “her five-year-old brain saw herself running into the street.” He paused. “What should I say?”

“Stop at the curb,” said Eloise immediately.

“Stop at the curb,” repeated Jason. “I can do that,” he said after a moment of reflection. “I can definitely do that.”

“Even if that wasn’t the role-modeling you received in childhood,” said Grami. There were smiles and laughter all around.

“That does help to explain some things,” Jason said. My teachers were forever telling me:

- Don’t forget your homework

- Don’t forget the spelling test tomorrow

- Don’t forget to bring back your permission slip

- Don’t drive above the speed limit

- Don’t talk back

- Don’t shout when you’re upset

And I usually managed to do just the opposite.” He smiled weakly.

“Oh my!” exclaimed Becky. “I need to tweak the way I talk to my 7th graders! I need to say:

- Finish your homework

- Remember the spelling test tomorrow morning

- Bring back your signed permission slip

- Follow the speed limit

- Speak respectfully

- Keep your voice level when you’re upset

“You two are fast learners,” said Eloise, smiling.

“No one ever explained it like this before,” said Jason. Becky nodded.

Eloise smiled, remembering how many times since her last visit she had wondered if Jason and Becky would put in the thought, time, energy, and practice required to tweak their communication style. Today Eloise had gotten her answer. Today Jason has said, “Stop at the curb.” And Amy had gotten the picture and done just that!

How do you talk to yourself?

How do you talk to others?

Say what you want to have happen. Create a one-step internal mental picture of the map you want the brain to follow. You may be pleasantly surprised at how this simple strategy can improve communication—with yourself and with others.